Abbie Hoffman

Steal This Urine Test

Fighting Drug Hysteria in America

2. Drugs Are As American As Apple Pie

3. Common Everyday Myths About Drugs

Free Heroin Programs Are Failures

Drug Education Campaigns Are Working

ANNUAL SUBSTANCE-RELATED FATALITIES

4. Warning! This Drug Is Dangerous

5. Warning! This Person May Be Dangerous

The Undifferentiated Continuum of Drug Use

7. Courting Disaster with the Constitution

8. Washroom Politics in the Age of Hysteria

9. Fear and Loathing in the Workplace

10. Enforcers at Work: All You Can Lose Is Your Job

11. The Short, Sordid History of Urine Screening

SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY CHART

The Immunoassays: EMIT and ABUSCREEN (RIA)

13. Golden Showers Come Your Way

Like It Or Not, Homework Helps

Prenotification or Random Screening

And Now a Short Message to Keep the Lawyers Happy

Synopsis

PENGUIN BOOKS

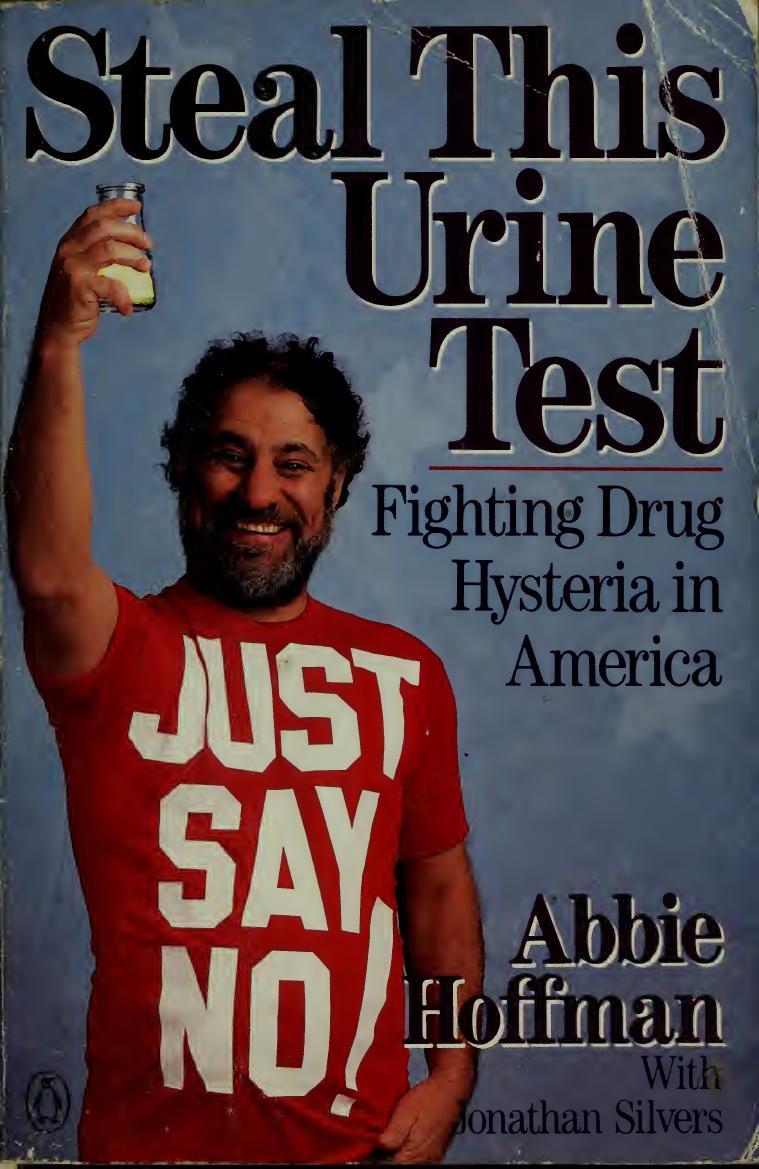

STEAL THIS URINE TEST

Abbie Hofiman has been an American dissident for more than a quarter of a century. In the early sixties he was involved in community organizing, Ban the Bomb activities, and the civil rights movement in the South. He was one of the most visible opponents of the Vietnam War, and he shot to national prominence as a result of the Chicago Conspiracy Trial. He spent most of the 1970s as a fugitive, remaining, however, politically active in a grassroots battle to defeat an engineering project for the St. Lawrence River. For the past several years he has been active in opposition to U.S. policy in Central America. Earlier this year he, Amy Carter, and thirteen others were acquitted of illegal-trespass charges growing out of efforts to block CIA recruiting on campuses. He is currently a consultant (at $1 a year) for Del-Aware, an ecological organization fighting to preserve the Delaware River. Newsweek recently commented that neither age nor arrests have dulled “his groucho-marxist humor or idealism.”

Jonathan Silvers attended the University of Pennsylvania and has written extensively on politics and culture. He is currently producing an original screenplay entitled Canvas, and is chronicling the 1988 Presidential election for a forthcoming book. He lives in New York City.

Also by Abbie Hoffman

Revolution for the Hell of It

Woodstock Nation

Steal This Book

Steal This Book: The Sequel (unpublished)

Vote! (coauthored)

To America With Love (coauthored)

Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture

Square Dancing in the Ice Age

Title Page

Steal This Urine Test Fighting Drug Hysteria in America

ABBIE HOFFMAN with Jonathan Silvers

PENGUIN BOOKS

Publisher Details

PENGUIN BOOKS

Viking Penguin Inc., 40 West 23rd Street,

New York, New York 10010, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ

(Publishing & Editorial) and Harmondsworth, Middlesex,

England (Distribution & Warehouse)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood,

Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Limited, 2801 John Street,

Markham, Ontario, Canada L3R 1B4

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road,

Auckland 10, New Zealand

First published in Penguin Books 1987

Published simultaneously in Canada

Abbie Hoffman, 1987

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Hoffman, Abbie.

Steal this urine test.

Bibliography: p.

1. Drug testing—United States. 2. Drug testing—

Government policy—United States. I. Silvers, Jonathan. II. Title. III. Title: Urine test.

HV5823.5.U5H64 1987 362.2'9386 87-12093

ISBN 0 14 01.0400 3

Printed in the United States of America

by R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Harrisonburg, Virginia

Set in Caledonia and Century Schoolbook

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

Dedicated to the workers of America, who have nothing to lose but their jobs.

Nothing so needs reforming as other people’s habits.

—Mark Twain, Pudd’nhead Wilson

Introduction to Independence

All my political friends have advised me not to write this book. They felt taking any position on drugs would lead to problems, dredging up the cocaine bust, now fourteen years old, but still a vulnerable wound. And that, in turn, could hurt my credibility as a critic of government policy. “Let sleeping drugs lie” was the general tone of advice. It would be a lot safer writing about my environmental protection battles over the past nine years, or my trips to Central America, the subject I most consistently address at lectures and rallies. Publishers love the idea of a book on how Amy Carter, myself, and thirteen others have just beaten the CIA in a Northampton, MA, trial. Even a book about the seven-year underground odyssey, a result of the cocaine arrest, would be a lot safer.

But my twenty-five-year chosen role as an American dissident, by definition, means that I have often had to reject the advice of well-intentioned friends and follow the dictates of my own conscience.

Politically, there are no points gained writing about drugs today unless you are willing to slam them. With the passing of the sixties and the hedonism of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll, the American Left has developed a puritanical streak almost as rigid as the Religious Right. The Black Political Caucus in Congress will probably scorn this book right along with the TV evangelists, in the same way that Women Against Pornography have adopted the Meese Commission pornography report as truth about sex. Neither side in the debate would recognize that drugs are being scapegoated in an attempt to avoid making badly needed social and economic changes in a disintegrating society.

Norman Mailer warned me, “Let the fascists have dope, it’s time to draw the wagons round and carefully choose the liberties we still have enough time to defend.” Ironically, we had this discussion while he introduced me to “the drug of defeat”—Scotch. We drained a bottle of the finest defeat available while mourning the passage of Enlightenment.

It’s been years since I could properly be called a “drug experimenter.” I used recreational drugs in the sixties, but I just don’t feel the same enthusiasm for the subject as I did when I was younger. I have gone on to other things, resisting pressure to challenge or champion the matter. This neutral position has been scorned by friend and foe alike, who feel I must repent, be bom again, even if it means compromising the truth as I perceive it.

There are Brownie points to be won by loud, firm atonement. But all renunciations, even sincere ones by people I know and admire—like Grace Slick and Dennis Hopper—seem misused and oversimplified by the media. The famous public renunciations look like cartoon confessions extracted under threat. They have the tone of fifties movies in which “Communists” confessed to being traitors on bended knees before someone’s mother or priest.

This book is not “preachy.” It does not beat the drum for or against drugs. It does not cry out for legalization, the passing out of free dope, or threaten to fill the reservoirs in Chicago with LSD. In the drug section (Part I), I simply apply what I’ve learned over the years to introduce complexity and sensibility into an area dangerously misunderstood. What you will read is an insider’s viewpoint on drugs, not dogma chiseled in stone. Every line should be prefaced, “In my opinion.”

What are these opinions? I believe society would be best served by abandoning the reigning turbulence and moving to a calmer plateau from which we could engage in drug education, research, and treatment programs with a decent chance of success. It’s easier to work on solutions without people shouting in your ear.

Without minimizing the problem of drug abuse, our attention should focus on equally serious problems, such as poverty, homelessness, unemployment, and inadequate medical care. I don’t believe we can cope with drug abuse on a meaningful scale until we are willing to tackle these more general and pressing issues.

I’m confident our healing community can come up with sound, workable strategies for all who need help, not just those who can afford it. However, I’m pessimistic about the chance that sane reasoning has against fundamentalist blind faith. Our scientific knowledge has increased dramatically in the past decades, but unfortunately the power brokers ignore this evidence, preferring to keep society as a whole in the dark ages. They offer stiffer punishments as the only solution.

On the one hand, this book is meant to be philosophical about drugs. On the other, it is meant to be precise, political, and activist on urine testing. This is a call to arms against a ritual that has nothing to do with drug abuse and a lot to do with controlling citizens.

My suspicions were aroused in 1982, when on a prison workrelease program I was subjected to constant, random urine testing. Because of actual drug use and/or faulty tests, a lot of inmates regularly flunked. The guards used the test results as blackmail, judging social behavior to be more important than actual drug use. Those who conformed to the warden’s image of the model prisoner were not punished for positive results, while those whose spirit of resistance had not been broken were.

My own case was unique. I was the most famous inmate on a work-release program in New York’s history, and an unrepentant troublemaker to boot. The press had drawn incredible attention to my case and conservative legislators were using it as an excuse to abolish the entire work-release program. The Daily News front page screamed, “ABBIE WALKS!” noting parenthetically “The Pope Goes Home.” (This was the biggest free job-wanted ad imaginable.) I saw it as my activist duty to defend this humane prison program with every act.

Offered several high-priced jobs, which under the rules I could have taken, I chose instead to work on a near-voluntary level as a drug-abuse counselor, returning to prison after each work day. I was meticulous about obeying the no drugs or alcohol rule, but on two occasions I flunked the urine test anyway. I refused to buckle under to lies. Threats of court suits, extensive publicity, and a demand for confirmatory testing were sufficient to scare the guards into ignoring the results. Beyond this, I began a campaign to enlist inmates, cheated out of privileges by a bogus test, in a court challenge against the screening process. I had lined up two of the best lawyers in the country (Gerry Lefcourt and Michael Kennedy) and felt a dozen plaintiffs were needed to make the proper challenge. No more effort than signing the suit was required; no inmate would have to pay a penny. But out of more than one hundred men, not a single one was brave enough to join the suit, and challenge the system. Remember, these are men who boast the lifestyle of the tough, macho con, ready to fight all comers. A bluff when it really counted.

Knowing something stinks in the system changes nothing. People have to be willing to stand up and be counted. Injustice is transformed into justice only when people at critical points in their lives are willing to risk the consequences, go for freedom, and Just Say No.

If not for these experiences, and the proliferation of the procedure, I would never have felt the urge to write about or even think this much about drugs.

Reading this book, I hope you get a sense that drug testing is the most tangible manifestation of Big Government policies aimed at destroying civil liberties that took decades to achieve. Already, close to 30 million Americans are being subjected to some form of chemical testing, and that number is expected to triple within five years.

This book asks a lot of the reader. Although I tried making the language accessible to the layperson, at various times you will need to be part scientist, part lawyer, part sociologist, as well as constant philosopher. Above all, I ask you to think.

Those of you who are new to my books might best start with Part II, where you will find more than you ever wanted to know about urine testing, more than is available in any other source. You will learn that manufacturers admit the tests are imperfect. You will see how margins of error are being badly misused to disgrace and fire complete non-drug users. Libertarians concerned about privacy will learn that a urine screen gives the Government or the Boss a complete chemical profile of everything in your body—information that you should quite rightly feel is none of their damn business. You will learn how a pseudo-scientific testing/ surveillance industry with strong assistance from the Reagan administration mushroomed overnight into a billion-dollar-a-year business, how these bladder spies have struck gold in urine, forcing people to give testimony against themselves and submit to unlawful searches and seizures. It will certainly surprise you to learn how widespread urine testing has become. You can follow the court battles over constitutional issues, and watch Congress, as usual, stand with its hands in its pockets.

With no hesitation whatsoever, this book gladly offers the most up-to-date advice on beating the tests. It also provides information to educate your friends, fellow workers, and politicians on how to ' resist and organize against mass screening before the practice becomes a permanent fixture in all our lives.

If you choose to read about urinalysis first, you should then return to the beginning and read the drug section. I hope by then you’ll be so outraged over urine testing that you’ll give some serious thought to what is being said about drugs, drug abuse, and hysteria—even some extra thought to politics, media, power, human values, and how things happen and don’t happen in our society.

I’ve deliberately avoided all profanity and rhetoric in the text, because I want this book to have a chance with readers who have honest concerns about their jobs and might be turned off by my “media image.” I have also done this so as to reach parents confused and frustrated when it comes to getting information they can trust about drugs and abuse. I have done this, I hope, without compromising what I believe to be truth, justice, and the democratic values of my country.

Abbie Hoffman Northampton, Mass. Patriots’ Day April 19, 1987

Part I: Drugs

1. Knee Deep in Hysteria

Let’s get something straight at the outset. This book is prochoice, pro-civil liberties, and antitotalitarian—American values as old as the Declaration of Independence. However, given the controversial nature of drugs, drug testing, and the prevailing political climate, it may well be mistaken as being pro-drug. That’s because virtually everything the average citizen sees on TV or reads in the newspapers on the subject is a combination of irrelevant nonsense and disinformation posing as antidrug knowledge. Anyone who disputes these watered-down factoids, as I do in this book, gets lumped with the deviant opposition.

The major institutions in our country produce, through mutual interests, a National Party Line (NPL) on any number of social issues. Defining this National Party Line would take several pages. Suffice it to say that the NPL is the modem American gospel, dictating rights and wrongs. Deviation from its scripture conjures up the label “heretic.”

The NPL on drugs dictates which drugs are morally acceptable and which are not. It also determines which users are socially acceptable and which are stigmatized outlaws. Narrow focus and strict categorization preclude meaningful debate on the topic. It is no different than, say, the NPL on Communism or God. An NPL emerges when a deliberative body, such as the U.S. Congress, reaches virtually unanimous agreement on an issue that is philosophically not so clear-cut. In other words, at some point adherence to blind faith, rather than scientific objectivity or common sense, becomes the criterion forjudging someone’s viewpoint. God is great, communism is evil, drugs do the work of the devil. End of the debate. An NPL thrives on simplicity. If an issue gets too complex, there can be no instant consensus. Once the NPL is set in place, few people are brave enough to venture into the issue’s complexity or perhaps even challenge the accepted dogma.

This consensus is rigid, bigoted, simplistic, and ultimately counterproductive to the treatment of drug abuse. It tries, by demanding strict obedience, to impose the moral and ethical values of the Enforcers on all citizens. This National Party Line is neither left nor right, but totalitarian in nature. Listen to the words of R. C. Cowan, writing in our most respected conservative forum, The National Review (April 29, 1983): “Our drug warriors (some fifty programs and agencies in the last seventy-five years) are an enormous, corrupt international bureaucracy that has been lying for years.” Unfortunately, there are very few critics on either side of the spectrum willing to challenge the shibboleths regularly accepted as truth.

It is a National Party Line filled with hysteria and hypocrisy, using fear and intimidation, a policy which, if history has taught us anything, is doomed to failure. This approach to drugs reflects the general wave of fear encouraged by the Reagan administration and its supporters: the welfare monster eating up all our tax money; crime in the streets; AIDS-ridden homosexuals molesting our children; the Evil Empire creating beachheads on our continents; the persistent terror of losing the nuclear arms race. This general hysteria manifested itself most strongly in the summer of 1986, when citizens of Fortress America could no longer visit Europe for fear of “world terrorism.” The odds of being on a hijacked plane were lower that season than of drowning in your own bathtub. But rationality and the European tourism industry could no more compete with the fashionable hysteria of that summer than facts could shield Americans from the next season’s fashionable bogeyman— the Drug Menace.

Drugs, naughty drugs, of course, have been a perennial favorite among pushers of hysteria. They symbolize the seven deadly American sins: laziness, violence, promiscuity, theft, godlessness, disrespect, and chaos. But nothing in memory seems to match what took place in the fall of 1986, during the national political campaigns.

Virtually every politician, from Jesse Helms to Jesse Jackson, advocated some kind of mandatory drug testing. Pierre DuPont, Republican presidential candidate from the state of DuPont (i.e. Delaware), demanded that every teenager pass a urine test before getting a driver’s license. The First Lady suggested the death penalty for dealers. Even an enlightened Senator like John Kerry (D-Mass.), who expressed doubts about “the accuracy of such tests, questions of privacy, and the potential for misuse by employers,” felt compelled by the omnipotent power of the NPL to vote against common sense and in favor of a Senate Commerce Committee bill calling for mandatory testing in the public-safety sector.

Moving from the absurd to the ridiculous, politicians urged the use of the military to “seal off the borders” from drug smugglers. A low estimate of what it would take to do this effectively might be three million soldiers. Not only would such a program cost billions of dollars, but were it to be implemented, it would soon be seen as be nothing more than a futile gesture. For example, drug abuse is a growing problem in East Germany, where authorities maintain that the chief crossing points for illicit drugs are the checkpoints at the Berlin Wall. Even if such a naive antiimportation policy could ever be implemented in the U. S., it would simply lead to the domestic production of more powerful synthetic drugs, no more expensive or complicated to produce than the imports. (See Chapter Three, “Common Everyday Myths About Drugs.”)

That fall, nothing less than a “War on Drugs” was declared. But as we will quickly see, it was a war at conflict with itself, with truth becoming the first casualty. Typical of the initiatives of the Actor-in-Chief, it was a war only in the symbolic sense, complete with all the trappings—the uniforms, the “combat footage,” the body counts, and, of course, the hundreds of millions of dollars spent. Like the long and difficult war we fought two decades ago in Southeast Asia, it seems the more the authorities claim we are “winning,” the worse the battles get—and the stronger the enemy grows.

Let’s take a look at the front lines of this so-called War on Drugs.

Here is an excellent opportunity to begin chipping away at the National Party Line. During one week in the month preceding the 1986 election, the news media were flooded with stories about an upcoming “secret” raid on a major Bolivian cocaine laboratory by U.S. troops. Military preparations, along with official statements, were fed to the public for five days running, even before the helicopters left for the jungle. The notion of a major cocaine lab that could produce millions of dollars worth of “devil powder,” the nerve center of an enemy with whom we are at war, must have seemed to the public, with such exaggeration, more fitting a description of the laboratories at Los Alamos.

Back to reality. A “major” cocaine lab is usually no more than a few thatched huts, some with large, gas-operated stoves upon which sit a half dozen restaurant-size aluminum cooking pots, and a few sheds to store coca leaves. A second smaller hut stores the rather primitive additives, such as lime, used to extract the active ingredients from the leaves. There also living and eating quarters for a dozen workers, lots of guns (this is, after all, a dangerous business), a well-camouflaged trail leading to an airstrip. Such is the humble reality of a “major lab”; a “minor lab” is a Bolivian family doing the whole process in their kitchen. (They might, incidentally, be using Bolivian money to kindle the flame, since that currency right now is considered the most worthless in the world.)

While the week of hoopla and ballyhoo preceding the invasion certainly gave ample warning to the lab workers to disassemble and disperse into the jungle, a process that would have taken about two hours, the workers chose instead to leave the labs undisturbed.

Why? Under the rubric “international cooperation” was hatched a virtual conspiracy that must have included the highest officials in Bolivia and the U.S., the armies of both countries, and major cocaine traffickers. They decided to put on a show that would dramatize to the world that Ron Reagan, Ed Meese, and the gang were “really” serious about this War on Drugs. As opposed to Nixon’s “Operation Intercept” or any of the dozen other initiatives we’ve waged over the past quarter century. Leaving aside emerging reports from the Kerry Senate Commission that the Contras are smuggling cocaine into the U.S. on Southern Air (i.e., CIA)

planes, (reminiscent of the well-documented Southern Air, i.e. CIA, heroin-running during the Vietnam War—see The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia by John McCoy), the major lab bust was, in reality, a staged fantasy in the War on Drugs.

When a deliberate fantasy is devised by Enforcers with great power, it is a good rule of thumb to suspect that something else is afoot. Troops in jungle camouflage, bearing automatic weapons, zooming in on Huey helicopters, may look like a war on drugs, but looks are the limit of this symbolic confrontation.

Another scenario on the front lines concerns the apprehension of “kingpins,” and what are routinely called “the largest drug busts on record.” The following story could be told about other illegal drugs, but cocaine or, to be precise, its more concentrated version—crack—is currently the media’s hot epidemic, so let’s stay out on the cocaine trail.

In February 1987, Carlos Lehder, a thirty-seven-year-old Colombian, was extradited to Miami with great sound and fury, identified by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and the news media as allegedly responsible for most of the cocaine on the streets of America. Peter Jennings, on ABC-TV’s “Nightly News,” associated Lehder with 80 percent of the illegal shipments to the U.S. Now, before we start passing out medals, let’s apply some minimal knowledge of cocaine trafficking and a little common sense.

Cocaine dealers can realize tremendous profits from a relatively small amount smuggled into the world’s largest seller’s market. Most of the trade is still in the hands of free-lancers. Everyone, from an ambitious family trying to break out of poverty in Bar- anquil, Colombia, to a caper-oriented “ring” of preppies at one of America’s most fashionable academies, Choate, tries his or her luck. Certainly there is a measure of control by organized, ruthless, and extraordinarily rich criminals, but a more likely kingpin might be a sixty-year-old Bolivian general, because it takes a lot of guns, murders, and political power to rise to the top echelon of smuggling.

Every six months or so, the DEA and the media parade a new and more powerful kingpin. Even more regularly, some prosecutor in our country holds a press conference announcing another “largest drug bust on record.” If any serious statistician or investigative journalist used his brain and a calculator, it could be easily “proved” that over the past four years, we have eliminated more than 400 percent of the drug supply for all users in America. In other words, capturing a “kingpin responsible for 80 percent of the cocaine” or making the “largest drug bust in history,” or adding bigger numbers to the body count (arrests) may be nothing more than propaganda ploys to justify the expense of the war on drugs. Ironically, after all the DEA’s “successes,” the problem keeps getting worse and worse.

In March 1987, the U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment released figures showing that cocaine imports rose from an estimated sixty tons in 1984 to one hundred-thirty tons in 1986. Heroin imports over the same two-year period rose from four to six tons. Meanwhile, federal spending to combat drug importation more than doubled, from $400 million in 1981 to over $820 million in 1986. Once again, the reality of the drug situation was laid bare: in the fifty years of an Enforcer-controlled drug policy, there is absolutely no evidence proving that increased federal expenditures for so-called “get tough” policies have any impact on supply. Neither do domestic crackdowns seem to matter. New York State special narcotics prosecutor Sterling Johnson compares these efforts to “digging a hole in the ocean.” His office claims that the price of a kilogram of cocaine dropped from $60,000 in 1981 to between $17,000 and $25,000 in 1986. Such a dramatic drop could only occur because of a substantial increase in supply.

The other end of the War on Drugs, the resolution end, has an equal number of staged plays. Lambasted for her extravagances during Ron’s first term (recall the presidential china, a refurbished White House, and several thousand-dollar only-to-be-worn-once gowns), the First Lady was anxious to shed her Marie Antoinette image. She scanned the New York Times Neediest Cases for appropriate causes. Fighting drug abuse was available, and she grabbed it. Let them eat cake, but not coke. Let’s take the most famous scenario: Nancy Reagan’s visit to the rehab center, where victims of the war on drugs are “cured” of their addictions. The highpoint of the visit is the moving testimonies of former addicts, no different from sinners confessing at a Jimipy Swaggert revival meeting. Who is not going to be moved by a sixteen-year-old black kid, tears streaming down her cheeks, talking about her awful.life with drugs, the wonderful people at Sunrise Village, and her determination to stay cured, to stay drug-free, by “just saying no”?

The centerpiece of the “just say no to drugs” campaign is the superficial ease of miracle treatment. Like its counterpart being played out in the Bolivian jungle, it too is deceptive. It is deceptive in two ways. The “cure the victim” morality play ignores drug abuse as a serious, complex, deeply rooted illness that is extremely difficult to remedy even on a long-term basis. The Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs, considered by many experts as the most complete study of drug addiction, reports a recidivism rate as high as ninety percent among “reformed” addicts.

In other words, chances are nine out of ten that within a few years, the “cured” patient will be back on the same drug or will have switched to another, more harmful addiction. There is much medical evidence that our rehab centers have concentrated for too long on the symptom—i.e. the drugs—and not enough on treating individuals. The more we learn about drug abuse the more we discover that it is an illness as dificult to cure as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, or any serious psychiatric illnesses. Indeed, some recent evidence suggests that substance abuse probably is a symptom of deeper psychiatric illnesses (such as anxiety or depression). In other words, contrary to popular mythology, drugs don’t take people, people take drugs.

On the mass educational level, the same problem of oversimplification persists. Telling serious drug abusers to “just say no” has about the same effect as telling serious depressives to “just cheer up.” It oversimplifies and masks the real clinical problem.

The other hoax being perpetuated by Nancy’s well-orchestrated sideshow to Ron’s action-packed war is the charade that government “really” cares about drug abuse. If that were true, there would be enough facilities to accommodate at least the many victims of drug abuse who voluntarily seek treatment. Daily, however, thousands trying to enter rehab centers get turned away for lack of space and funds. Worse, rejection from treatment centers leads many addicts to desperate acts, including suicide.

In the fall of 1986, the peak of the drug hysteria, strange things began happening. Twelve-year-old kids were praised as heroes for turning in their parents, reminiscent of the Hitler Youth days; PTAs called for random strip searches in high schools; rock ’n’ roll was again being scrutinized in congressional hearings for references to drug use; professional athletes were forced to squeal on teammates, then publicly confess and parrot the National Party Line on television. Unconstitutional restrictions on travel, with strong components of racism, mushroomed in popularity. Police on the George Washington Bridge set up roadblocks, tying up traffic for hours, hunting for suspected drug users. In Fort Lauderdale, police stopped motorists daily, distributing cards saying “WARNING: You Are Entering a Dangerous Area Known for Drug Sales.”

The media was far from being a passive, objective observer of this phenomenon. To the contrary, it fueled the flames with sensationalism. Newsweek and Time devoted five cover stories to drugs from March to November 1986. Newsweek, in one dose of hyperbole, compared the drug crisis to “the plagues of medieval times.” The CBS News documentary, “48 Hours on Crack Street,” earned the highest ratings for a documentary in the past five years. NBC Nightly News, in the seven months preceding the election, ran 429 segments on drugs, a record sixteen hours of air-time. Throughout this media onslaught, criticism of the government’s anti-drug policies was virtually nonexistent. That, free speech lovers, is what you call a National Party Line!

All this and more reflected, and still reflects, the kind of hysteria this country has not seen since the fifties’ “crackdown on communism.” National talk shows and the weeklies ate it up and presented “all sides” of what was essentially a one-sided debate. Then came the urine test, a ten-dollar mass surveillance device. Some members of Congress, bidding for re-election, actually challenged their opponents to urine test-offs. Some form of drug testing was being demanded for nearly the entire population as the linchpin of the War Against Drugs. The urine tests became to the drug hysteria of the eighties what the loyalty oath was to the Red Menace of the fifties. In both cases, cooperation with a simple but meaningless and degrading ritual offered “proof” of good, productive citizenship.

That’s the way it was in the fall of 1986: the public was so hyped up that polls identified drug abuse as the number-one concern of the voters. A USA Today poll showed 77 percent of Americans felt this way, and the poll was echoed throughout the media as accurate.

Imagine, drug use the number one concern in a country that is rapidly losing its industrial base to runaway corporations and foreign competition; that has just become the largest debtor nation in the world; where budget and trade deficits zoom out of control; where 200,000 farmers are going bankrupt each year; where Wall Street scandals are reported weekly; where 34 million people live below the poverty level; where more than 3 million go homeless; where 9 million are out of work; where supply-side polarization is causing the middle class to vanish; that is panicked by, but not about to cure, AIDS; where the Office of Technology Assessment predicts that within ten years half our drinking water will be contaminated with toxic chemicals; where schools are churning out functional illiterates; where roads and bridges are falling into dangerous disrepair; where a rising tide of racial terrorism, exemplified by incidents in Cummings, Georgia, and Howard Beach, Queens, threatens gains made during the past quarter century; where an entire generation of young people seems to be growing up without hope; and where the potential for nuclear obliteration haunts us all.

Clearly the priorities are wrong.

In the midst of these hazards, somehow a problem in which the annual fatalities number only in the hundreds (a very small number when compared with fatalities related to any of the major legal drugs) was blown totally out of proportion. The voters somehow nominated drug abuse number one on the list of social ills, and, I’m ashamed to say, 80 percent of my fellow Americans agreed that urine tests were a good way of stopping it. (Incidentally, that’s roughly the same percentage that favored loyalty oaths back in 1953—a percentage, I would guess, that also held true among the public three centuries ago, when tests for witches were popular in Salem.)

Of course, it was campaign time, so Democrats and Republicans engaged in a “can you top this?” verbal duel over drugs. Issue- hungry candidates thought up the most outlandish things they could say or do to show they were tougher than their opponents on drugs. No one, needless to say, was tougher than the Cowboy himself, Ronald Rambo Reagan. The voters did not exactly exert free will in elevating drug abuse to the top of the social-problem heap. They were simply carrying out by rote the instructions of this strong father-figure.

Polls showed that Reagan was the most popular President of the century, even more popular than FDR. Reagan was playing a yuppie version of Juan Peron, pushing a hard-working, drug-free, entrepreneurial culture, while Nancy, as his Evita, cared for the poor, helpless losers. The two campaigned tirelessly to push these lopsided priorities. More to the point, the Reagan administration, by committing us to “wiping out this evil scourge,” used the fight against drugs as a litmus test of patriotism: who among us was brave enough to “just say no” to the Reagans and demand a return to fair play?

Reagan was out to protect “traditional family values.” This, mind you, from a divorced man who never goes to church, whose daughter publicly lampooned him in a novel, whose son, a contributing editor to Playboy, had made a big splash by pulling down his pants on “Saturday Night Live,” and who claims he has no time to see many relatives, including his own grandchildren. These were “traditional family values” Hollywood-style, with scripts and special effects.

Well, politics, like football, is a game where the ball takes funny bounces. Within weeks, even days, after the elections, the Great Communicator was exposed as either the worst liar, the biggest bungler, or the dumbest President ever. The critics were too stunned to figure out which. Who would have guessed that he would suffer the greatest drop in presidential popularity (20 percent) ever recorded in a single month? The “Teflon presidency” had now turned to cellophane, and all could see that the Emperor had no clothes.

Throughout his reign, Reagan had sworn on a stack of Bibles that he would never do business with terrorists. Who would have guessed that one of those Bibles was already on its way to Iranian “moderates”? Then came revelations and confessions that for eighteen months we had been trading arms in hopes of getting hostages released. After threatening our allies not to trade with Iran, an “outlaw” country, it was revealed that millions, perhaps even a billion, dollars worth of arms had been sold to none other than the Ayatollah Khomeini himself. All this skirting of our laws, the will of Congress, and the defiance of public opinion was done in service of Reagan’s obsession with controlling the destiny of Central America.

That deceit exists in high places is not a new lesson. Certainly we must have learned at least this from Watergate. But what a great hoax Reagan perpetrated. He had us convinced that here was the Leader of the Free World, who, though he may have made mistakes here and there, was really a sincere man who believed what he said. Go tell that to the dead Marines in Lebanon and the dead civilians in Tripoli. While Reagan and the CIA were misinforming the world that Libya was chiefly responsible for terrorist acts such as the bombing of the Marine barracks in Lebanon, he not only knew the culprit was Iran, he was secretly supplying weapons of death to its arsenal.

While the scandals of Reagan’s foreign policies occupied the headlines, the misinformation and broken promises of his domestic policies will be seen in the battered society he leaves in his wake. The major pledges Reagan made for domestic programs in the campaign of 1986 were all broken within weeks after the elections. Whether over the issue of aid to the elderly, student loan programs, or cuts in deficit spending, the Reagan administration had with all deliberate speed gone back on its campaign word. A pledge in October 1986 to support the $20 billion Clean Water bill, desperately needed for the health of our country, was changed to a veto only weeks after the election.

But easily the biggest bluff of all was Reagan’s “sincerity” on drug abuse. As election day drew near, the President claimed that fighting drug abuse would be the number one priority for the remainder of his term. “We seek,” he said, a “drug-free generation.”

Congress, trying to stay even with the Gipper, passed the $3.96 billion Anti-Drug Abuse Act. It was the fifty-fifth federal anti-drug action in eighty years. On October 27, 1986, Reagan signed it, saying, “The American people want their government to get tough and to go on the offensive and that’s what we intend with more ferocity than ever before.”

Not three months later, Reagan, preparing his 1988 fiscal budget, cut nearly $1 billion from the anti-drug budget. Funds for enforcement, which this book certainly would not endorse, nevertheless were cut a drastic 60 percent. Public service education campaigns lost $250 million. The crudest blow was the recommendation that absolutely no federal money be spent on drug treatment programs. “It’s so phony and pitiful and, let’s face it, this is why people have a cynical view about politics,” said Congresswoman Barbara Kennelly (D-Conn.). “It’s absolutely unconscionable, terrifyingly stupid,” said Senator Alfonse D’Amato (R-NY). “If it’s such an epidemic, why the cutbacks?”

And that, in a nutshell, is the reality of Ronnie’s War on Drugs and Nancy’s concern for the victims of drug abuse. Far from being part of the solution, they became an intricate part of the problem. Worse, the damage they did to our values, our knowledge, our priorities, our sense of hope will take decades to correct.

2. Drugs Are As American As Apple Pie

I really have to laugh when I hear politicians and preachers shout about “wiping out all drugs in America.” I laugh because they would have an easier time trying to wipe out electricity. Contemporary America is arguably the most drug-ridden culture in the history of the world. Exactly how “drugged” it is depends on one’s perspective.

A drug is defined in Talber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary as “any substance that when taken into the living organism may modify one or more of its functions.” To narrow this vague description, it may be helpful to state at the beginning that we are not talking about extremes—food on the one hand and poison on the other. Our drug domain includes the vast category of substances in between. Some of these substances are considered illegal, but the overwhelming majority are not.

Understand that legal and illegal are political, and often arbitrary, categorizations; use and abuse are medical, or clinical, distinctions. Science evolves before politics, and its evolution is less haphazard, less fraught with punishment and stigmata. What’s illegal today might be legal tomorrow—and vice versa. As our historical references demonstrate, political attitudes, punishments, and laws change quite rapidly.

Putting a wholesale stamp of illegality on a drug, or attempting a prohibition, often has just the opposite effect as what was intended—increasing curiosity to try the prohibited substance. Rebelling against authority has been considered by psychologists as one of the motivating forces behind illegal drug use. The primary effects of any ban seem to be: inconsistency in quality; a (slight) difficulty in purchase; and an enormous increase in the cost of the prohibited drug. In a trade known for lawlessness, laws of supply and demand still dictate the dynamics of the market. This is what attracts organized crime to the selling end and breeds random individual crime on the purchasing end. This criminal element becomes another serious social problem. Not only does the user sometimes take on society’s label as “criminal” and act accordingly, he or she is exposed to a subculture filled with violence of the worst kind. The world of Scarface does exist.

Virtually anything requiring a prescription can be found listed in the voluminous Physicians’ Desk Reference fPDR/ It is an annual publication which gets thicker every year, currently listing about 300,000 different drug products. This is the ammunition the doctor has at his battle station, firing away as he chooses. Choosing not to prescribe means not supporting one of the country’s biggest industries—and disappointing the patient’s expectations. We are conditioned early on that a doctor’s visit is worthless unless we leave with prescriptions. No one believes fruit juice, rest, and aspirin alone are worth $50 a visit.

The High Times Encyclopedia of Recreational Drugs is the most complete catalogue of illicit, or outlawed, drugs available. Not as useful for a doorstop as the PDR, it lists only 5,000 different substances. Some, like marijuana, are very old; marijuana can be traced back 12,000 years in human history (see Marijuana: The First 12,000 Tears by Dr. Ernest L. Abel). Others are as new as the inspiration of the garage scientist.

Both sources barely hint at all the drugs available to the consumer. Over-the-counter, off-the-shelf potions by the thousands are also used, and abused, by the public. Heavily advertised remedies and pseudo-remedies create the notion of instant cure and instant relief. It’s a very American concept—immediate satisfaction, one that has even influenced so many of our personal relationships?

Far from being a purely contemporary practice, drug taking goes back to the times before the first Europeans set foot on this continent. Authorities on the colonial period such as Barbara Melosh, Curator of Medical Science at the Smithsonian Institution, and Dr. Peter Wood, Medical Historian at Duke University, maintain there is evidence that more than two hundred natural psychedelic drugs were cultivated among indigenous Indian tribes. Stimulants, depressants, antipain remedies of all sorts were derived from bark, leaves, wild plants, berries, anything that grew wild. Religious rituals went hand in hand with the general pharmacology of the tribe. According to Rayna Green, Director of the American Indian Programs at the Museum of American History in Washington D.C., Indians used tobacco, or nicotiana, only in a mixture with barks and leaves, and primarily for ritual purposes. “It was the white man,” she said, “who decided to smoke it pure, who cultivated the most potent forms and made smoking common practice.” Other natural substances, used both for medicinal purposes and to achieve an altered state of consciousness, arrived early on these shores as part of the African and Caribbean slave trade.

Certainly, by the time the leaders of the American Revolution got around to writing the Declaration of Independence in the late eighteenth century, drug use had proliferated. Constitutional experts have still reached no consensus as to what Thomas Jefferson meant by “the inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” —especially that last item. All agree that he at least had in mind the rights of the individual being protected from a powerful enforcement-prone government. But no expert has concluded that the Founders felt obligated to protect the general public from the mind-altering substances which were all around them. This isn’t to say they approved of intoxication or getting stoned. The Founders didn’t feel it was an overwhelming concern, and controls were limited.

Dr. Alfred Young of Northern Illinois University, a leading Jeffersonian scholar, told me: “Borrowing from the tradition of common English law, the Founding Fathers put privacy at the highest level of values. ‘A man’s home is his castle’ influenced all their thinking. The urine tests and all modern invasions of privacy would have horrified them.”

Given the task of inventing a nation, drugs and enforcement were not very high on their list of social problems. That’s not to say substance use and abuse didn’t exist. As Barbara Melosh states,

“We can assume there was widespread use of every sort of natural drug available.” We can deduce the early lawmakers’ attitude of laissez-faire or ambivalence because it took more than a century to consider outlawing any of these extremely old-fashioned drugs.

Experts who study the usage of opium and cocaine derivatives at the turn of the present century (just prior to their prohibition), claim that although the price was relatively cheap and the supply plentiful, the ratio of use to abuse did not differ significantly from that of today. The same can be said of marijuana prior to its being outlawed in 1937, or of LSD prior to 1966. I remember asking the late Dalton Trumbo, one of the blacklisted Hollywood Ten and a thirties activist, if the old Left was into marijuana. “Hell, we’re so old, we smoked it when it was legal,” he replied.

Perhaps getting high was not one of the rights the Founders protected by “the pursuit of happiness,” but libertarian attitudes still prevailed. Although some states came down hard on sodomy, no scholars have discovered any state laws restricting what we would call drugs. George Washington, typical of Virginia planters, grew hemp, which is marijuana. For the most part, this material was used to make rope, but there’s no record of anyone being arrested for smoking the rope, or any other substance. Since fields sometimes caught fire, and the acrid fumes entered the lungs, people must have known something was happening. Benjamin Franklin, the most widely traveled and exotic experimenter of the group, probably used opium to check a painful kidney stone problem. Now, the fact that Ben experimented with drugs or was a sexual libertine for most of his life is not exactly highlighted by the DAR or the Bicentennial Commission. Enforcers write history faster than they can write laws. What we read in our grade-school textbooks is, obviously, a watered-down and slanted version of history. A thought-control mechanism. To question the “official version” of history, you must do some extra digging. You must rebel.

For example, you rarely read about the drugs that proliferated in America in’the nineteenth century. But some historians say the U.S. had more drug addicts per capita in the second half of the nineteenth century than it does today. Mark Twain was a big cocaine fan. Buffalo Bill, Kit Carson, and other legendary western heroes smoked, drank, and ate just about everything the Indians did. Peyote use was common. Opiates were readily available to the general public: doctors prescribed them, made their own concoctions, and pushed them directly, while drugstores sold them over the counter. Hundreds of medicines containing opium or its derivatives—with names like Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral and Godfrey’s Cordial (a mixture of opium, molasses for sweetening, and sassafras for additional flavoring)—were available in grocery and general stores. Opium was the poor man’s high: narcotics were much cheaper than liquor in those days and were generally considered safer.

Couldn’t get to the store? No problem. The Sears & Roebuck catalogue offered a two-ounce bottle of laudanum—opium doused in alcohol—for eighteen cents, or two dollars for one and a half pints. As for the kiddies, well, children should be seen and not heard. There were plenty of patent medicines for them, too, with names like Mistress Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, Mother Bailey’s Quieting Syrup, and Kopp’s Baby Friend. They all contained opiates. At the giant 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, a Turkish hashish stand “to enhance the Fair experience” was very popular. Dr. John Morgan, Professor of Pharmacology at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, estimated that 5% of the population was physically dependent on over-the-counter opiates.

Doctors prescribed opiates for pain, cough, diarrhea, and dysentery. In fact, the nineteenth-century doctor prescribed morphine the way doctors today give out tranquilizers—with a shovel. One 1880 textbook listed fifty-four diseases that could be alleviated with morphine injections. Morphine was even given to alcoholics, in the belief that it was better to be hooked on narcotics than on alcohol. (This practice continued in the rural South until narcotics prohibition got serious in the late thirties.)

Interestingly, the demographics of users back then differed greatly from users today: they were largely female, mostly white, and mostly in their forties. Women users, outnumbering men by nearly three to one, were an easy target for addiction—first, because opiates were prescribed for menstrual and menopausal discomforts; and second, because it was thought unwomanly to be seen drinking liquor in public, or to have it lingering on your breath. So while husbands were in town chuckin’ ’em down at the local saloon, the wives were back home demurely taking their opium. Smoking cigarettes, as the Virginia Slims folks like to remind us, was considered unfeminine. Fortunately for their lungs’ sake, the wives hadn’t “come a long way” yet.

It was all legal back then: opium was being imported, and morphine was then being extracted and manufactured from it. Opium poppies were also grown inside the U.S., in places like Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Florida, and Louisiana in the East, and in California and Arizona in the West. They were often homegrown, no more difficult to raise than the colorful spring varieties in my own flower garden. Over time, a few states took it upon themselves to ban opium. Congress couldn’t pass any antidrug legislation until the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, and didn’t register the first all-inclusive drug act until 1942 with the Narcotics Control Act.

I can still remember, as a child, seeing official licenses to distribute opium and coca leaf products in my uncle’s pharmacy and even later on the wall of my father’s medical supply company in the late forties.

The federal role in enforcement began in earnest in 1937, with the appointment of Harry Anslinger to the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) and federal enactment of the Marijuana Tax Act. This was barely three years after the repeal of alcohol prohibition. Anslinger was the first drug czar of this country, and he helped direct much of the subsequent propaganda. Viewing the movie Reefer Madness will give you a glimpse into the narrow mind of Czar Anslinger.

One strong Anslinger supporter was William Randolph Hearst. His yellow-journalism newspapers ran numerous antidrug (especially anti-marijuana) stories with strong racist overtones. These articles were read into the Congressional Record as fact. Larry Sloman, in his book Reefer Madness, quotes Anslinger testifying before Congress: “Most of the marijuana smokers in the U.S. are Negroes, Mexicans, and entertainers.” An interview with Anslin- ger’s close friend Dr. James Munch revealed that the Drug Czar hated jazz, which he labelled “satanic music.” According to Dr. Munch, Anslinger believed that the combination of jazz and marijuana caused white women to have sex with Negroes.

Surprisingly, the strongest lobbyist for the autonomy of Anslin- ger’s agency was J. Edgar Hoover. Wishing to preserve the pristine image of the FBI, Hoover realized that drugs and police corruption went hand in hand. Other supporters included many of the legal drug, tobacco, and alcohol industries, who benefitted economically from the repeal of the prohibition on booze and the imposition of prohibition on now-outlawed drugs. Incidentally, the American Medical Association campaigned against making marijuana illegal, since so many doctors had been using marijuana-based medications.

The chief benefactor of all these laws was organized crime, which during the years of alcohol prohibition had developed a sophisticated system of smuggling, production, marketing, distribution, and bribery. The principal loser was the taxpayer.

One major difference between the nineteenth century and now was in how society treated narcotics users. They were not considered a social menace a hundred years ago, and there was little outcry for prohibition. Moral sanctions against opiate use were rare—addicts weren’t fired from their jobs, people didn’t divorce or turn in addicted spouses, and families weren’t split up, with kids placed in foster homes. In short, there was no attitude problem toward addicts such as we have today; drug users continued to function—erratically, perhaps—in society. Today the opiate user is ostracized, resulting in the formation of an outlaw subculture cut off from society.

Getting from permissive to restrictive took some imagination on the part of the Enforcers. In arguments for the prohibition of narcotics, racism was extremely prevalent. The first anti-opiate ordinance was drafted in 1875, in San Francisco, where the target of the Enforcers was oriental opium dens; Chinese were accused of using such dens to trap white women into slavery. In the early twentieth century, during the congressional debate that led to the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, boll weevil congressmen from the South claimed that cocaine made blacks lust for white female flesh and also made them impervious to bullets. A Southern sheriff testified how he had to “change from .32-caliber to .38-caliber bullets in order to kill niggers crazy on cocaine.” (See Drugs and Minority Oppression by John Helmer.) Anti-marijuana campaigns came of age in the thirties in part because it was a “Mexican habit.” It’s no coincidence that there was a strong concurrent sentiment to “drive Mexicans back across the border.” During efforts to increase the funding and scope of anti-drug legislation in the fifties, through the Kefauver Committee on Organized Crime, it was clear that the targeted users were young urban blacks.

Various legal and moral tactics have been used throughout the century. The attitudes of the police against hippies during the sixties was a new form of cultural prejudice. There was no mistaking the vicious hostility “flower children” elicited from police just by their presence. Little due process or civil rights were observed in thousands of drug busts and frame-ups. Drug enforcement was the easiest way of destroying a counterculture which was allegedly breeding revolution. In 1969 alone, 400,000 arrests for marijuana possession were made.

Biases, moral and political, continue to divide the country.

Contemporary evidence of extensive use of drugs can be found on the shelves of any convenience store. Nicotine is responsible for 200,000 to 300,000 deaths a year, a hundred times more deaths than from all illegal drugs combined. And it is not only legal, but is encouraged by the government in the form of farm subsidies.

Nicotine, incidentally, is the only drug where the overwhelming majority of its users are clinically considered to be addicts. Use and abuse are virtually synonymous where smoking is concerned. Surprisingly, the New York Times Magazine recently ran an excellent article, “Nicotine: Harder to Kick Than Heroin.” I suspect this was hard for Times readers to believe, because of strong class prejudice against heroin. But there is little medical argument with this point. A psychiatrist at Rockefeller University in 1967, after examining and testing heroin addicts, reported: “Cigarette smoking is unquestionably more damaging to the human body than heroin.” Subsequent studies over twenty years have confirmed this.

It is extrerpely difficult to determine how widespread the use of illegal drugs or the misuse of legal drugs is, especially in a time of hysteria, when “no” is a much safer answer on a questionnaire form or in a phone survey. There is no area, with the possible exception of the arms race, where cooked statistics are so blatantly

DRUGS ARE AS AMERICAN AS APPLE PIE 29 used to justify budget requests as with drugs. Still, both the Enforcers and those championing a more liberal policy toward drug use agree that the number of users is in the millions. The latest National Institute of Drug Abuse figures (for 1985) claim that 62 million Americans have tried marijuana, and 18 million had smoked it in the month of the survey. About 22 million have tried cocaine, 5 to 6 million within the month. Nearly 2 million have used hallucinogens. These are large figures, indeed, but they are dwarfed in comparison to the misuse of prescription drugs, alcohol, and cigarettes. At least 100 million Americans drink alcohol regularly.

The percent of misuse is even more difficult to determine, although a general estimate has been placed at 14 percent of all drug use. Also, nearly 70 percent of drug misuse has been attributed to prescription drugs.

Alcohol, as controversial as heroin, is our second biggest killer drug—120,000 annual fatalities. Readily available in thousands of different forms, it is a drug that destroys lives across the whole fabric of society. It affects the alcoholic’s family, friends, and coworkers. (See Chapter Three, “Common Everyday Myths” for all comparison fatality figures.)

Experts claim the new, popular teenage craze today is crack, though crack is hardly new; people have smoked cocaine for a few thousand years. It is, however, more stable (less affected by humidity, temperature, and sunlight), inexpensive (cut with more additives than cocaine), and easier to smoke in this form (which makes it more dangerous).

But I suspect an “epidemic more severe” than crack and not being talked about at all is the widespread use of easily accessible wine coolers. Promoted on television as if they were harmless soda pop, these wine coolers contain approximately as much alcohol as beer and wine. Barties and Jaymes are more than just homespun philosophers pushing soft drinks; they are responsible for getting the next generation plastered to the gills.

Alcohol is a distant second to the popularity of nicotine among the young. Most kids who smoke started before they were thirteen! According to the New York Times Magazine, the average smoker needs 70,000 hits a year. That’s what you call a chimney, not a human.

Sugar, caffeine, and chocolate are additional substances that if misused, or used by the wrong individuals, can be bad for one’s health. Although legal, all three are pharmacologically considered drugs.

Then there is a whole class of readily available substances, rather benign in nature and not generally thought of as drugs, which can be used as if they were drugs. When I was young, sniffing modelairplane glue was a popular way to fool around, and equally popular was a movement to ban the substance. In prison, sniffing shellac fumes from a pail is a common—though not very exotic—way of getting high. Morning glory seeds became so popular during the sixties as a mild hallucinogen (you have to eat loads of them) that the large seed companies were forced to coat the seeds with a bitter substance so it wouldn’t taste good. Nitrous oxide, or laughing gas, a most interesting drug, is sort of legal: if you buy a can of certain aerosol whipped creams, hold the can upright, slowly bend the nozzle, and deeply inhale the gas propellant. You can open the bottom of the can with an opener later to get the yummy cream. Ha! Ha! Even nutmeg can be used for more than just food seasoning. If you live in a rural wooded area, there are probably dozens of wild things that if brewed, stewed, or eaten raw will alter your state of consciousness, even produce hallucinations. If you really love New York, Wild Man Steve Brill’s botanical tours of Central Park are becoming a popular attraction. He will happily point out the natural highs growing wild in Central Park, but this is strictly an educational expedition. “I show all kinds of mushrooms,” he says, “edible, poisonous, and hallucinogenic.” The Department of Parks frowns upon consumption of park flora and fungi, so be forewarned.

Drugs are everywhere in our society, readily accessible and often used or abused. A wine made out of dandelions in Mississippi, a fraternity house brew at the University of Minnesota which relies on sweat-laden athletic socks as its chief ingredient—the ingenuity of Americans knows no limits when it comes to getting high.

New drugs enter the market continuously. Like Brooke Shields’s blue jeans, these very chic substances are referred to as “designer drugs.” Most just have initials that mean nothing or correspond to a rock group. But the most popular one is termed “Ecstasy.” The reason I say “termed” is because many of us suspect that Ecstasy is several different drugs grouped under one name, that it is a derivative of MDA, which is also suspected of being a class of drugs rather than a single substance. It is hard to keep a listing of the names of all the new drugs coming on the market, let alone their molecular structure. The Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, easily the best chronicler of n^t^drugs, will by the time this book is published have seen abusers of many “1987” drugs. The 1988 models promise to be more varied.

The movement to outlaw certain drugs is sometimes as old as some of the drugs themselves. Of course, no law can be made banning a drug that precedes the invention of the drug itself. In order to make a drug illegal, there has to be a period preceding its illegality when the drug was legal.

Now, making drugs illegal is a tricky process. Lawmakers trying to outlaw cannabis, for example, would have as tough a time as committees trying to decipher rock music if only words were involved. There are probably a thousand or more words to describe grass, pot, or its current slang expressions—“smoke” in the North, “dube” in the South. That’s also a problem in reverse: there could be many drugs with just one name. A law making “Ecstasy” illegal just wouldn’t sound right.

Banning drugs means banishing specific molecular structures. Governments can and do legislate against a molecular structure, but any creative science-minded pusher can rearrange some of the molecules, and presto—you’ve got yourself a custom-made high that produces just about the same high as the outlawed one. Only the new molecular structure isn’t illegal, because even the fastest lawmakers in the world can’t outrace shifting molecules.

Lately, politicans are trying to isolate and outlaw a rather narrow range of molecular structures. The Enforcers, being just as faddish as drug users, have their own top ten, headed by whatever is that year’s “epidemic drug of the year.” Thirty years ago it was marijuana. Twenty years ago it was LSD. Then STP. Then heroin. Then cocaine. Then angel dust (PCP). Then crack. Tomorrow it will be Ecstasy or Adam. Then probably Bazuco—a cheaper, more stable version of crack. Something is always just around the comer, ready to be the new “in” (as in hip) and “out” (as in epidemic) drug.

The Law tries to keep informed, and the users try to keep ahead. Fifty years ago, the cat-and-mouse game was alcohol, and if we were to look at other countries and their cultures, we could find periods where coffee or cigarettes were considered the most evil substances. It’s all part of the same cycle. Enforcers have been working overtime to try and suppress one thing or another since the beginning of time, and with extremely poor results. The only real consistency has been the zealots’ ability to label someone else’s notion of pleasure illegal. Uniforms, badges, guns, budgets, and bribes have also been pretty consistent.

Remember the concept that every illegal drug has to have a prior period when it was legal. The reverse is also sometimes true, with legal drugs having had a prior period of illegality. It’s possible to trace this back to the source of humanity: “In the beginning there was a substance; and some took that substance and got high. Others took that substance, and didn’t get high. Then arose someone who partook of that substance, and got sick, or had an awful time.”

Now who do you think got up and said, “Hey, that’s illegal!”? It certainly wasn’t the ones getting high. They were having too much fun. Those feeling nothing probably said, “Why bother? It’s no big deal.” No, it must have been the one(s) having a bad trip.

Forerunners of the modern-day Enforcer in effect passed a judgment that said, “if you’re getting high, you’re now an outlaw, because you’re outside the laws we’ve just created.” From that first bad primeval trip, and from subsequent definitions of legality, things kept getting more and more confusing.

Fundamentalists say that drug taking is a crime against God and nature, although I’m sure what they really mean is a crime against the Protestant ethic, since pleasure can’t be put in a savings account or postponed to the hereafter. Dr. C. Creighton, a British physician, concluded in 1903 that the Bible is filled with many drug references. “Honeycomb,” “honeywood,” and “calamus” are thought to be pot. The manna that fell to the wandering Jews in the desert is now thought to have been pollen in a windstorm—and it probably contained ergotine, an active ingredient in LSD. David and Solomon were often downing exotic libations of one sort or another. There probably were a lot of nasty drugs in Sodom and Gommorah, though a more benevolent God might have tried something other than incinerating all the inhabitants. There were surely a lot of drugs at the Tower of Babel: not only were the people talking in all sorts of different tongues, they were also talking from different states of altered consciousness, since by that time there were many different substances floating around the marketplace.

Let me make another, more modern, point. In 1956, James Olds discovered that electricity, if transmitted through electrodes implanted in a particular area of the cortex, can get rats high. (It wasn’t Olds that discovered it, rather the laboratory rats he tested. The rats told Doctor Olds they were high. What can I say, lab rats have big mouths.) Dr. Olds himself never tried his means of pleasure, and I don’t blame him. My only experience in taking electricity turned out to be a bummer. That was the time I grabbed two live wires and had this incredibly bad trip. It was so bad that for many years I considered starting a social movement to ban electricity.

What do you think is the most efficiently run corporation in America? If you answered IBM, you were operating on yesterday’s information. Today, Merck Co., Inc. is considered by the Wall Street crowd to hold that position. Merck pumps out chemicals by the thousands. For the politicians, this presents no problem, because legal drug manufacturers contribute greatly to campaign war chests. However, for the clinician concerned about drug addiction, most of these drugs can be misused and abused. Drug companies make their money on overprescribing, not underprescribing. They advertise heavily and give free samples. I can’t tell you how many Celtics games I’ve had to see surrounded by boring hospital supply buyers, riding the payola wagon of my father’s medical supply company.

When the AMA, joining the fall 1986 hysteria, called on physicians to report drug abusers to the police, anyone knowledgeable in the field must have had a good laugh. The New England Journal of Medicine believes that as a group, doctors have the highest abuse level in the country.

When it comes time to define what is a good or bad substance, the dictionary is of little value. Like laws and history, the dictionary is also written by the Enforcers. The original Enforcer in this thought-control sector was Noah Webster. He was a Puritan, and if the Puritans ever got their hands on history, they would surely take out all the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll—and the real Benjamin Franklin, too. No surprise that Webster, rigid prude that he was, tried to remove all hints of earthly pleasure in his original dictionary.

Attorney General Edwin Meese, today’s leading Enforcer of morality, is descended from a long line of Puritans. Meese is not only tough on drugs, but he is also tough on sex, which his blueribbon commission equated with violence. Puritan Meese, before he was Attorney General, was the district attorney of Alameda County in California, where he had a chance to come down hard on the sixties hippies and radicals of Berkeley. (Ronnie was governor at the time.) Puritan leaders are somber, righteous types who believe their pogroms of repression and suppression are the will of God. Casual sex and drug-taking are activities indulged in by, well, savages. Throughout history, attempts have been made to isolate or exterminate the heathens—for their own good.

Psychotherapist Anne Wilson Schaef, in her current book When Society Becomes an Addict, argues that our nation as a whole is exhibiting all the symptoms traditionally attributed to the individual addict. She postulates an “addictive system,” which, among other things, denies reality, needs to control everything around it, and employs other habitual mechanisms—like lying and compulsive stimulation—to “feed its habit.” Schaef demonstrates the wafer-thin line between addiction and obsession—claiming our culture is hooked on work, sex, and money—the Yuppie Triad.

Not all mood-altering drugs are alien to the body. Science has isolated chemicals in the brain called endogenes, which affect our moods and state of consciousness. Apparently, they can trigger themselves or be triggered by a variety of externally induced substances, but the point is, they are already inside us all.

Long ago, when I was a clinical psychologist at a mental hospital, one of our clients was an air swallower. Air swallowers gulp air and force it into their stomachs rather than their lungs. They do this, they say, because it makes them feel high, probably through over-oxygenation of the blood system. It’s a very dangerous practice, since on occasion the stomach will burst like a balloon. Fortunately for the Enforcers, ever ready to outlaw a new substance, air swallowers are not very common. Which is just as well—it’s rather difficult outlawing air.

Bulimia, an illness which causes the sufferer to go on enormous food binges followed by self-induced vomiting, leads to dehydration and rapid weight changes. Unlike air swallowing, it is fairly common but an equally dangerous malady. It leads to no “high,” but satisfies a psychological desire.

For too long discussion about drug abuse and addiction has been substance-oriented. I am trying to point out the futility of this by showing how extremely benign substances, even air and food, can be abused. This is not to say heroin, barbiturates, coffee, chocolate, and Afrin nose sprays offer similar risks, but rather that looking at individuals and their relationships to drugs will tell us much more about the nature of illness. Hopefully, this will lead us to more fruitful research and treatment programs.

And to conclude our discussion with a note on recreational drugs, here’s a quote from a study by the advertising agency D’Arcy Masius Benton & Bowles reported in the New Republic (3/23/87). The report, “Fears and Fantasies of the American Consumer,” surveyed 1,552 U.S. households, asking them to identify their primary source of pleasure and satisfaction. Surprisingly, “drugs are four times as popular as grandchildren as a source of pleasure and satisfaction to the average American.” So if we have to say no to drugs, which apparently make a lot of people happy, what are we supposed to say to our grandchildren when they call collect!?

I’ll hold by my initial premise, that drugs are as American as apple pie, that in reality they surround us and comprise us. Virtually all Americans, with the exception of a few Christian Scientists and scores of hypocrites, ingest quantities of drugs. Drugs are an integral part of our long history, and will inevitably play an even greater role in our future. To deny this fact is to deny reality.

3. Common Everyday Myths About Drugs

The Billion-Dollar Bust

The monetary value of illicit drugs—always publicized in the media when yet another “biggest drug bust in history” is reported—boggles the mind. In no other area of economics are figures so readily distorted.

Let’s say, for example, that 500 pounds of cocaine are seized after it has crossed the border and is in the importer-wholesaler’s house. The price the dealer paid for that very large quantity would be about $1 million, or $2,000 per pound. This represents the lowest price and highest product quality.

Enter the nares. The public has been fed an elaborate story of keen-eyed border patrols, coordinating efforts with local, state, and national enforcement agencies. Month-long stakeouts, round- the-clock surveillance. Ha! Someone in Bolivia, Colombia, or stateside probably had a grudge or wanted to cut down on competition and made a single phone call to a desperate agency, the tip-off, a favor which may be returned in kind. “Hello, Rodriguez, this is the DEA. Tuesdays from three to five p.m. are all yours.” “Gracias, companero. ”

A smuggler for a major Colombia cocaine cartel testified before Congress that he “donated” $10 million to the CIA for the Nicaraguan Contras. “The cartel figured it was buying a little friendship,” he said.

Now, one of “the biggest busts in history” is about to unfold.

Since Geraldo Rivera has brought a camera crew and promised two minutes on the evening news, the Enforcers put on an extra good show. It’s supposed to look like “Miami Vice,” and it does. Only this is the real thing!

As to price, for some strange reason that one-million-dollar shipment has miraculously and immediately become worth $2 billion! Wow!

Here’s how it happens. If the bust never took place, the 500 pounds, which was originally at 96 percent purity, would be immediately doubled (stepped on, cut, etc.) at the wholesaler’s with a look-alike additive, usually an Italian baby laxative (the reason why many coke users do extra number-twos in the toilet). These 500 pounds are distributed in single-pound units for about $10,000 each. That’s now $10 million. Each pound at the distributor’s is doubled with more additive, reducing the purity to 24 percent of the original shipment. And these 2,000 pounds are subdistributed as one-ounce packages for $1,000 each. That’s now $32 million, if the calculator is correct. But wait, we’re not done yet! Street cocaine varies from 6 percent to 20 percent purity when bought in single-gram units or processed into crack. Let’s just leave it at 24 percent purity. The price on the street: $100 per gram. There are approximately 907,200 grams in 2,000 pounds. Sell each gram at $100 a shot, you get an end price of $90,718,500. Make it an even billion, since most will be sold at less than 24% purity. A thousandfold increase! Not bad, considering that nothing has left the premises.

The day after the bust, the TV news will be trumpeting, “Major drug raid nets $1 billion in coke!” Isn’t that amazing! Using this economic system, I can prove that a car you just bought for $10,000 is actually worth $500,000. But I’d have to break it down and sell each part separately to very desperate parts buyers in countries under economic embargo by the U.S. I couldn’t sell in bulk, have any lost or unsold parts, or any overhead, travel or labor costs. And no middle people to take risks, do work, or make profit.

The rare newscaster adds the phrase “at street value” to the one billion. Some media outlets automatically halve all drug figures reported by the Drug Enforcement Administration or the local DA’s office. This is called responsible journalism. But all use some maximum potential street profit figure instead of the price actually paid by the importer.

Why is it done this way? Here again, inflated numbers make everyone look good—the DEA, the local sheriff, the hard-working cop, the news team; even the apprehended dealer puffs up his chest a bit. Certainly his lawyers are happy, thinking they’ll actually get their fees paid.