Catherine Amey

The Compassionate Contrarians

A history of vegetarians in Aotearoa New Zealand

Introduction: The compassionate contrarians

Vegetarianism in Britain and New Zealand

The Canterbury Dietetic Reform Association

Harold Williams and vegetarianism in the 1890s

Arthur Daniells and food reform in Napier

Ellen White visits New Zealand

Maui Pomare, Seventh Day Adventism, and health

Nettie Keller and the Christchurch Medical and Surgical Sanitarium

A vegan doctor visits New Zealand

The Sanitarium Health Food Company

Vegetarianism beyond the church

3. Is meat-eating a necessity?

‘Do everything’—vegetarianism, feminism and the temperance movement

The Christchurch Vegetarian Society

Christchurch Agricultural and Pastoral Show

Ettie Rout and physical fitness

Wilhelmina Sherriff Bain and the peace movement

Jessie Mackay and animal rights

4. The kinship of all living beings

Peace, animal rights, and vegetarianism

War and the export trade in the twenty-first century

‘Disloyal and seditious propaganda’

Vegetarians in Mount Eden Prison

Vegetarians in prison in the 1950s

Freedom School and the final days of Beeville

6. ‘Glorious is the crusade for humaneness’

Theosophy arrives in New Zealand

Animal rights and vegetarianism in the 1940s

The New Zealand Vegetarian Society and rationing

Sandra Chase and the ‘Humane Killer’ Campaign

Theosophists and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection

The Vegetarian Society in the 1970s

7. Flavours and recipes from many traditions

Dutch vegetarians in Greymouth and Wellington

Hindu vegetarians in New Zealand

The International Society for Krishna Consciousness

Vegetarian food from many countries

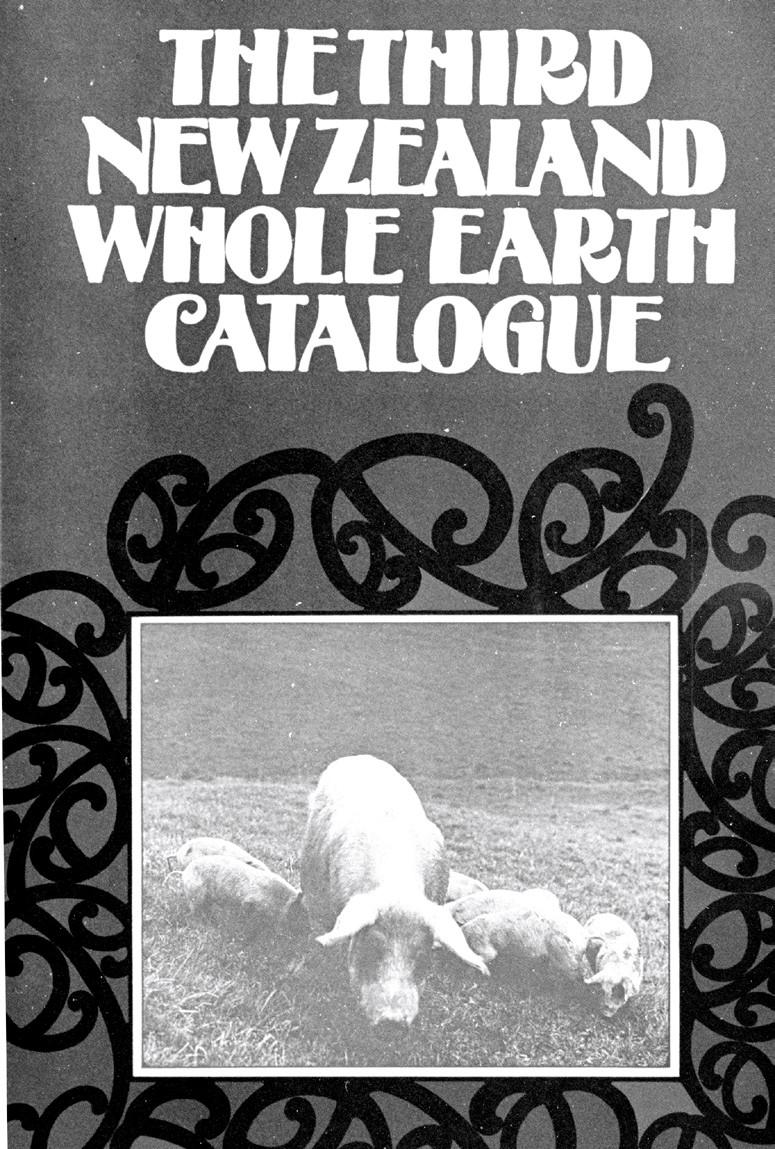

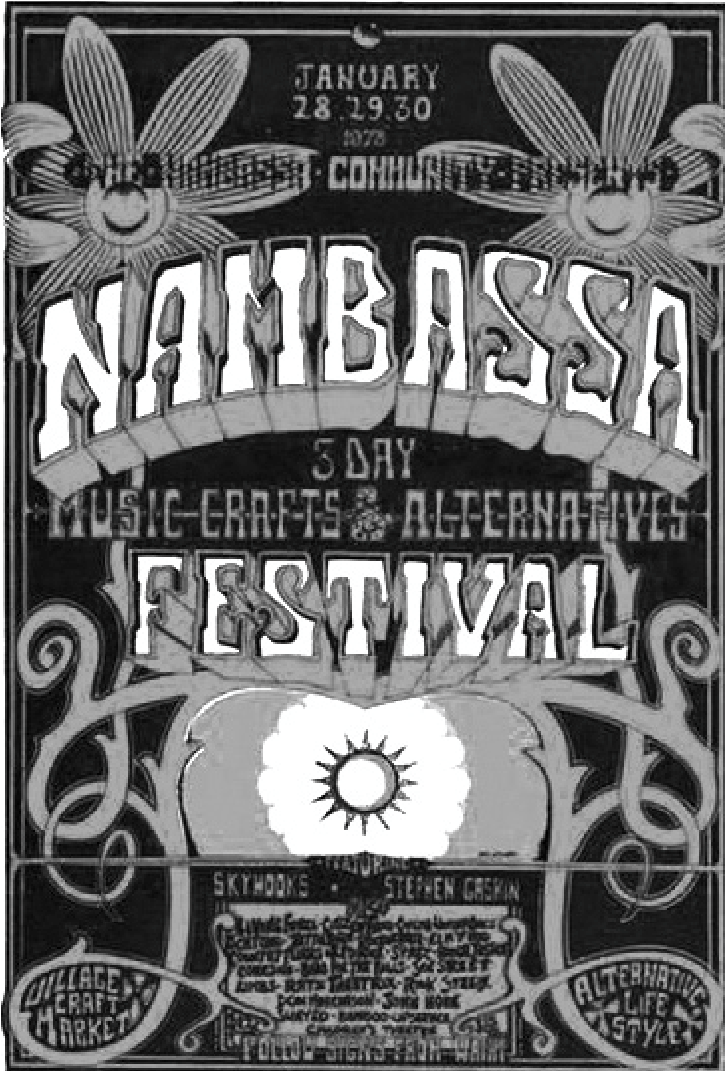

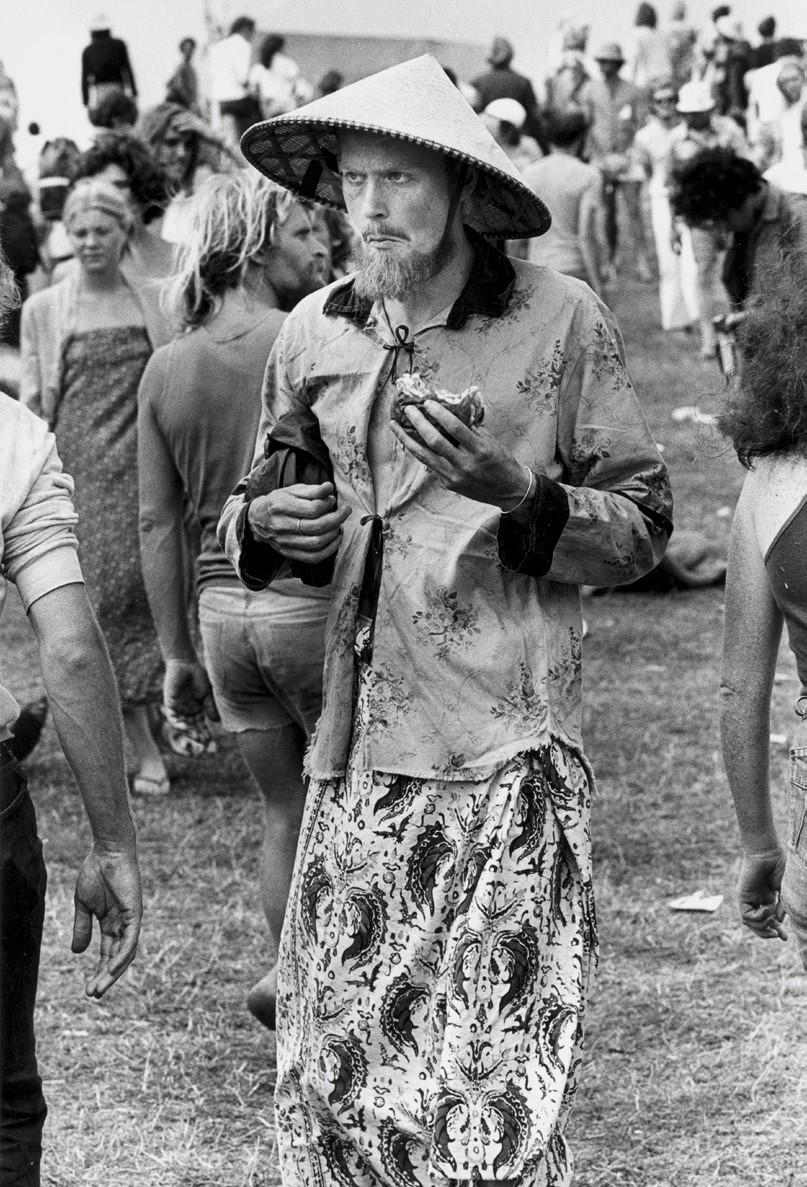

The literature of the counterculture

Tim Shadbolt and Renee de Rijk

The Fri and the antinuclear movement

The women’s movement and vegetarianism

Vegetarian restaurants and recipes

9. Chickens, pigs, cows and the planet

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

The

Compassionate

Contrarians

A history of vegetarians in

Aotearoa New Zealand

Catherine Amey

[Anti-Copyright]

Anti-Copyright 2014

May not be reproduced for the purposes of profit.

Published by Rebel Press

P.O. Box 9263

Marion Square 6141

Te Whanganui a Tara (Wellington) Aotearoa (New Zealand)

info@rebelpress.org.nz

www.rebelpress.org.nz

National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Amey, Catherine.

The compassionate contrarians: a history of vegetarians in Aotearoa New Zealand / Catherine Amey.

ISBN 978-0-473-27440-5 (pbk.)—ISBN 978-0-473-27441-2 (PDF)

1. Vegetarians—New Zealand—History. 2. Animal rights activists—New Zealand—History. 3 . Political activists—New Zealand—History. I. Title.

613.2620922093—dc 23

Cover design: Kate Logan

Bound with a hatred for the State infused into every page

Set in 10.5pt Minion Pro. Titles in Futura Std Heavy 18pt

Foreword

The rat was white and very clean, with a sensitive, twitching nose and a gentle expression. I looked at her in the cage, and she looked at me. Instantly I realised that it was quite wrong to kill her simply so that I could grind up her liver and measure the levels of her liver enzymes—an experiment that had been performed by thousands of biochemistry students before me on thousands of rats. Sadly for this particular rat, a tutor was standing right next to me. He pulled the rat out of the cage, twisted her neck, and handed her warm body to me. He looked at me sympathetically. ‘I don’t like this either,’ he said. ‘That’s why I’m switching to botany.’

There I was with the dead rat and a scalpel. Eventually I cut a gulf into her limp stomach, exposing the miniature, human-like organs packed into her warm belly. She smelled of fresh butcher’s mince. I felt nauseated and guilty. Not long afterwards, I read Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation, and decided not to kill any more rats, and also to stop eating meat. Laboratory experiments and satisfying my taste buds both seemed trivial and inadequate reasons to take away a life. At the time, I knew few other vegetarians. I joined the New Zealand Anti-Vivisection Society and marched through the Wellington streets to protest against animal experiments. I was too timid to become actively involved, however. Later, while I was working for an environmental group at Wellington’s Peace and Environment Centre in Cuba Street, I gradually realised there were lots of other veggies and vegans around—in Peace Movement Aotearoa, the Wellington Rainforest Action Group, the anarchist Committee for the Establishment of Civilisation, Save Animals from Exploitation, Wellington Animal Action and the Vegetarian Society. I became involved in animal rights, and joined the anarcha-feminist Katipo Collective, which included many vegans. Over time I began to wonder about the history of vegetarianism and animal rights in this country. I had a vague idea of hippies in the 1960s eating lentils and not much else. In 2001 I went to an animal rights conference and met Margaret Jones, then in her seventies, and an inspiringly energetic anti-vivi-sectionist and Marxist. She had been campaigning against animal experiments since the 1930s, and remembered the vegetarian socialist playwright George Bernard Shaw staying at her house when she was a teenager. Quite a long time later I read David Grant’s Out in the Cold, a history of conscientious objectors during the Second World War. Grant described Norman Bell, a leader of the No More War Movement in Christchurch:

A scholar with first-class honours degrees from Canterbury, London, and Cambridge Universities, Bell had been barred from teaching and standing as a Labour candidate in the 1919 election because of his stand against the First World War. He lived, often precariously, as an outside examination tutor for Canterbury University students, and as a private teacher of Esperanto, German, Greek, Hebrew, and Maori. In many ways an otherworldly figure and a man before his time, his refusal to wear leather shoes as a protest against the killing of animals for food, was more than a little strange to observers in a conformist 1930s society.[1]

And so this book began. I would like to thank more people than I could possibly mention here. I’m particularly grateful to Christine Dann, for long-term support, advice, and the correction of many errors and to Rebel Press for bringing this project to fruition. Many thanks are also due to Janine McVeigh, and the 2009 Northland Polytechnic class, Ryan Bodman, Nicky Hager, Mary Murray, Lorraine Weston-Webb, Eric Doornekamp, Kevin Hague, Ann M., Hans Kriek, Ranjna Patel, Valerie Morse, Megan Seawright, Lyn Spencer, Ross Gardiner, Tanya Chebotarev, Sian Robinson, Michael Morris, Tanya Tintner, Peter McLuskie, Debra Schulze, Katy Brown, Eric Wolff, Margaret Jones, the research librarians at the National Library of New Zealand and many others. Words can’t express how grateful I am to Mark Dunick for his support and love.

Introduction: The compassionate contrarians

The miseries...[in the world] do not come to us by chance,

but by a system of utterly false relations of people to one

another and towards the animal creation.

—Jessie Mackay[2] </centre>

On a rainy Friday evening in July 1885, an unnamed country gentleman ventured through the mud to a community concert at the Stratford Town Hall. Arriving slightly late, he walked into the hall to hear a singer praising sauerkraut over roast beef and plum pudding. The mere suggestion that vegetables could be preferred to meat was offensive, and he sat down to write a piece for the Taranaki Herald, complaining:

‘I should like to ask this gentleman if he considers it the part of a patriot to take advantage of a public platform, with the eyes of the world upon him, to disseminate the pernicious doctrine of vegetarianism? What is to become of Taranaki if beef goes out of fashion?’[3]

For a hundred and fifty years New Zealand’s economy has largely depended on the bodies and infant milk of animals.[4] Historian James Belich characterises meat in colonial society as ‘the essence of food, representing the rest...it symbolised human domination of nature, and was a marker of prosperity and status.’[5] The ‘mystique’ of grassland farming is part of our national identity, shaping our lives, our diets and the land around us.[6] Nineteenth century European colonists settled in rural areas, clearing the forests to create pastures for sheep and cattle.[7] With so much food on the hoof around them, they turned to a diet laden with meat, alcohol, and bread.[8] Early New Zealand was ‘a place of plain home cooking, heavy on meat dishes and sweetened by cakes, with little time for “foreign muck.”’[9]

Yet there have long been idealists who disagreed with the meat-eating majority. Even though New Zealand kills millions of animals every year, there is also a significant history of concern for animal suffering—the first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was formed in Canterbury in 1872.[10] From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, ethical vegetarians have drawn attention to the contradiction between petting animals, and chewing on them. Their arguments challenge us at a very basic level, questioning what we put on our plates, and why. Just as conscientious objectors (some of whom did not eat meat) refused to participate in the wars of the twentieth century, ethical vegetarians refuse to be complicit in the slaughter of millions of animals. They remind us that the tidy, plasticwrapped packets of fl esh that we buy from the supermarket were once warm with life, and they point out that different and perhaps more compassionate choices are available to us.

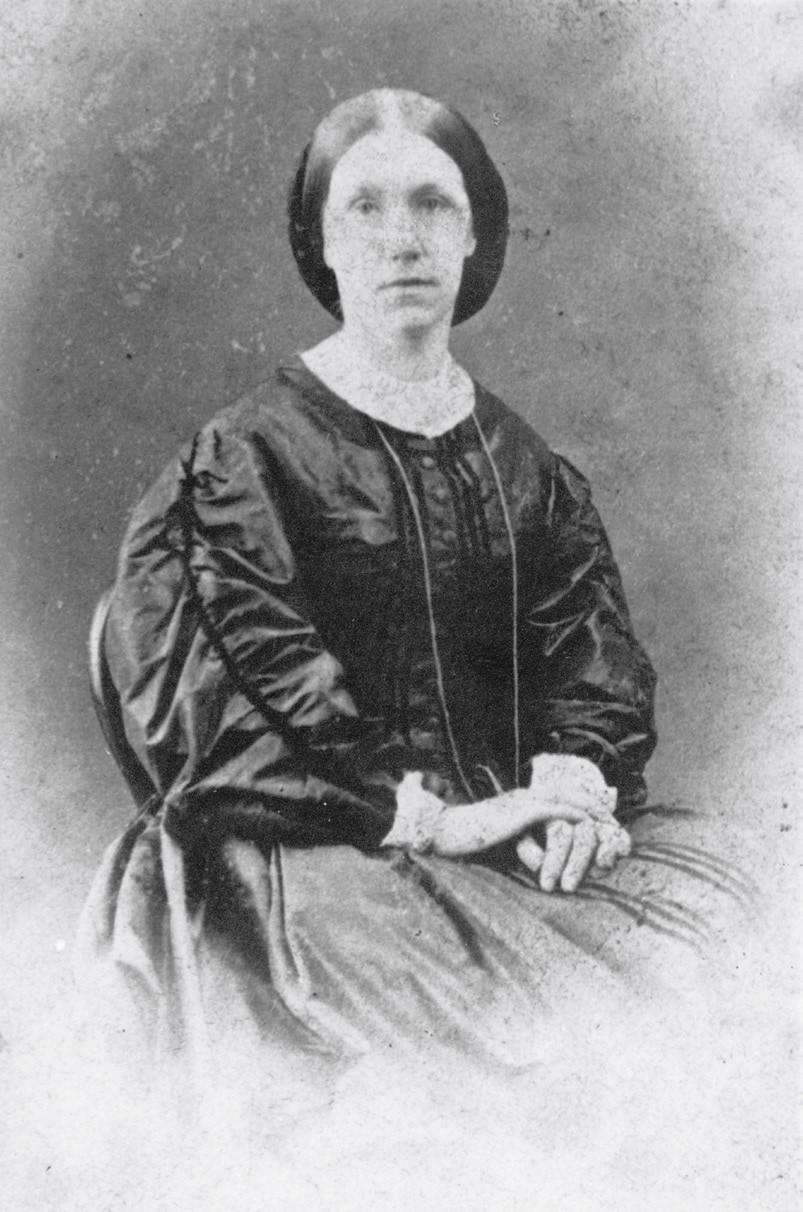

Vegetarianism has a long history in Aotearoa, dating back to early Maori communities. For example, according to the oral literature of Ngati Awa in the Eastern Bay of Plenty Region, the ancestor Toi-kai-rakau (Toi the wood-eater) ate vegetable foods.[11] In the nineteenth century, early British colonists explored meatless diets. Mary Richmond arrived in Taranaki from England in the 1850s, joining her husband’s family in a small farming community, which raised pigs and cows for meat and milk. Mary believed that ‘no apparent law of the universe or design of the creator can make it right to destroy life.’[12] Several decades later, young Harold Williams stopped eating meat in imitation of Tolstoy. The idealistic Christchurch teenager argued that ‘it is wrong to kill animals for food, not only on the animal’s account but also on the slaughterer’s.’[13]

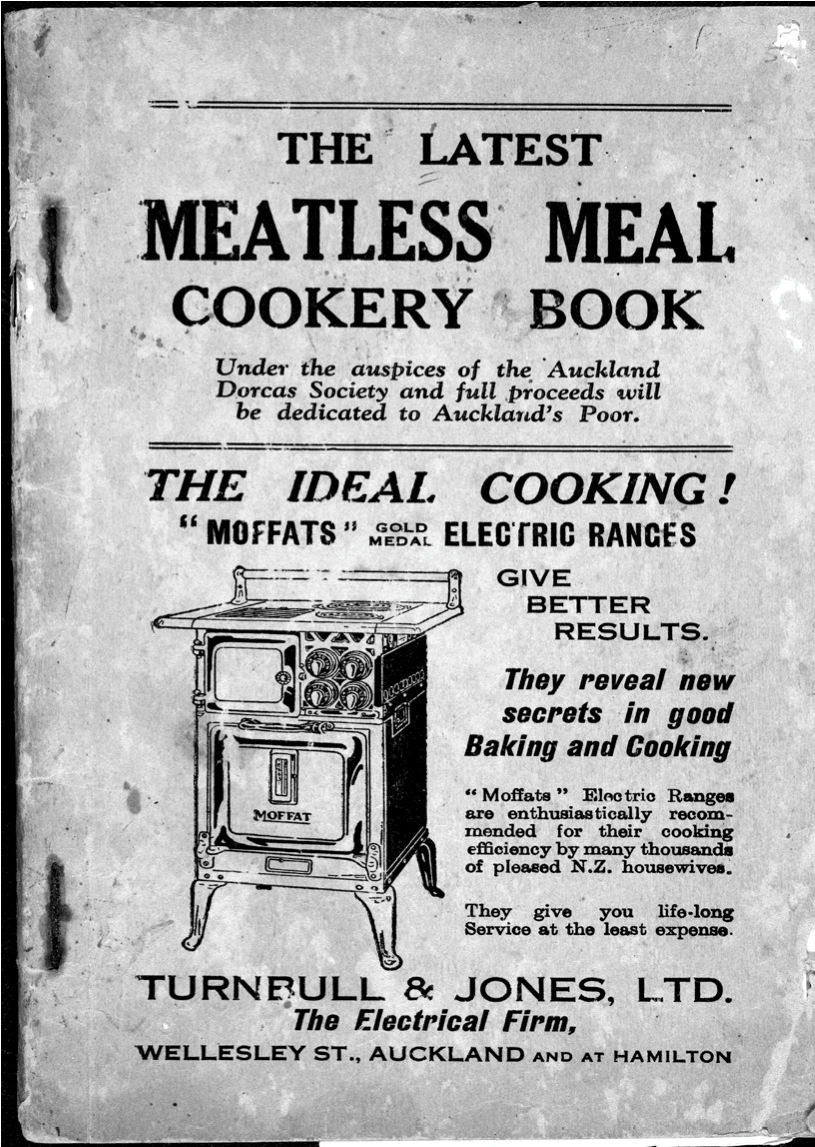

The late nineteenth century was a time of upheaval, of questioning the status quo, of experimenting with natural diets and imagining utopias.[14] The early vegetarians in this book were courageous and unconventional, cherishing ideals that were heroic and occasionally eccentric. They dreamed of international disarmament, equal rights for women, prison reform, the dismantlement of the British Empire, anarchism, socialism and a ban on alcohol. Among them were Seventh Day Adventists, theosophists, free-thinkers and spiritualists. They included public fi gures such as the suffrage and temperance campaigner Kate Sheppard, the judge and politician Sir Robert Stout, and Maui Pomare, the fi rst Maori doctor. In the early twentieth century Adventists started up vegetarian cafés, published cookbooks, and opened health food factories. Generations of children grew up munching on Weetbix, produced in those same factories. Over the years Weetbix and Marmite, once ‘faddish’ health foods, became iconic New Zealand products. Women’s rights and temperance campaigners also explored meatless diets.[15] The White Ribbon temperance magazine published recipes for savoury lentil loaf, and nut plum pudding.[16] In the 1920s and 1930s pacifists such as James Forbes and Norman Bell set up the Humanitarian and Anti-Vivisection Society, probably New Zealand’s first animal rights group. Bell looked to a future in which ‘all exploitation of living beings by other beings will eventually become repulsive to man.’[17] During the Second World War, hundreds of young men were imprisoned for resisting conscription. They included vegetarians, and the dining hall at the Strathmore detention camp even had a special vegetarian table.[18] In the early 1950s young Lucien Hansen refused to register for military service, declaring that ‘under no circumstance will I ever take part in any warfare, whether it be against colour, creed or nation...! am a non-meateater, and refrain from killing wherever possible.’[19]

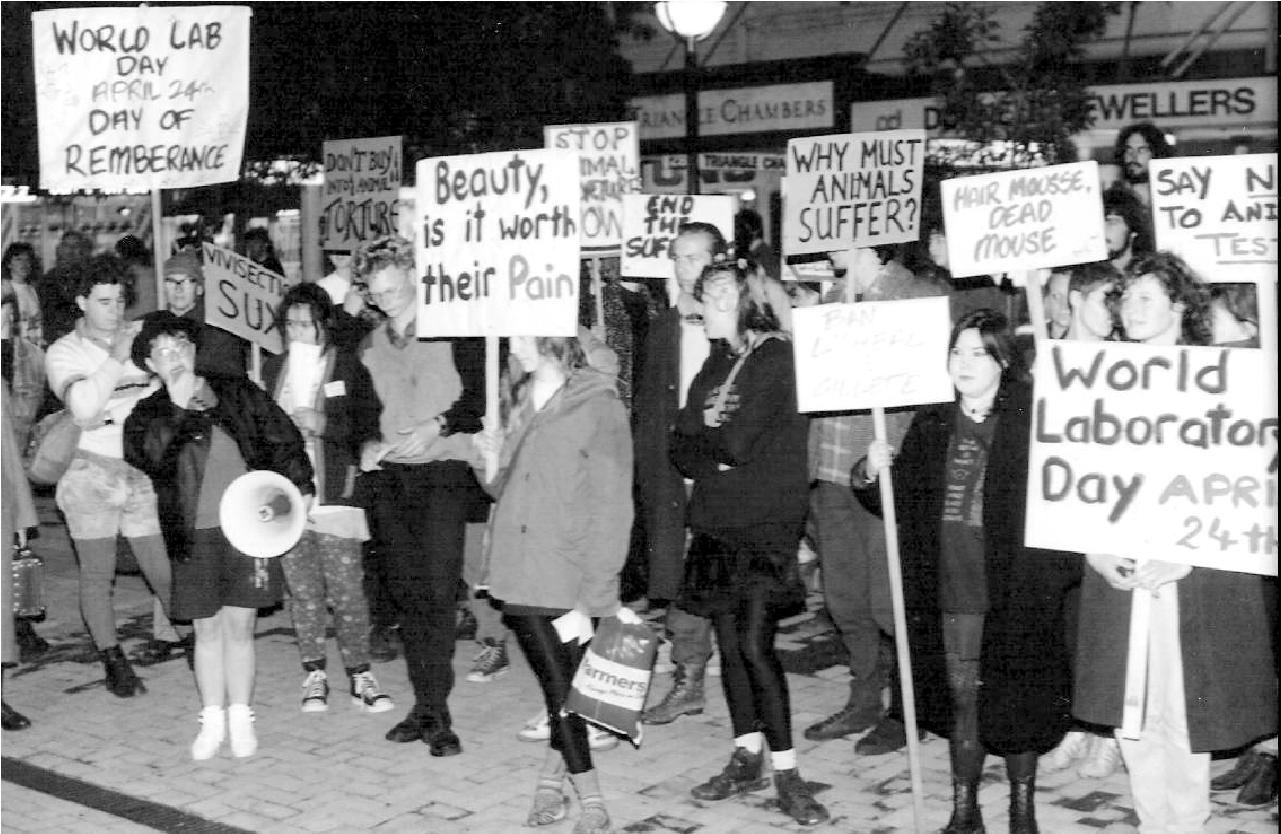

Theosophy, a syncretic religion that drew from Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity and the occult, also influenced vegetarianism and animal rights trends in New Zealand. Geoffrey Hodson, an English theosophist lecturer, set up the New Zealand Vegetarian Society in the 1940s. He and other theosophists campaigned against animal experiments and investigated slaughterhouse practices, protesting that animals were slowly bludgeoned into unconsciousness with hammers.[20] In the 1960s and 1970s the counterculture emerged, and young people explored more ethical and natural ways of living. Meanwhile, New Zealand’s cuisine was becoming more diverse, as immigrant communities introduced tantalising new herbs and spices, and New Zealanders travelling overseas discovered exciting flavours and textures—dhal, falafel, tofu, spanakopita, Asian stir-fries and fake meat dishes. The following decade, a new animal rights movement emerged from the 1970s protest movement. Anti-vivisectionist Bette Overell led hundreds of people through the Wellington streets to protest against animal experiments, and some activists turned vegan, boycotting all animal products.[21]

Over the years, our attitudes towards animals and food have shifted. New Zealand cuisine is no longer just about roasts, sweet cakes and stodgy puddings. Meatless options are almost everywhere, and are crammed with subtle and surprising flavours. On Saturday mornings at my local Newtown vegetable market in Wellington, the rhythms and voices are as complex and varied as the flavours and aromas—golden deep-fried tofu, fresh noodles, sticky rice, gleaming eggplants, wheatgrass, chillies, crisp stalks of lemongrass, feathery green bunches of coriander. A caravan dishes up savoury vegan mushroom, quinoa, and walnut burgers, and a middle-aged gentleman with a contented dog and a guitar strums protest songs next to the tofu stall and urges us all to ‘cheer up and smile.’ Vegetarian and semi-vegetarian diets have become particularly attractive to young people. A 2001 study found that twenty-six per cent of people chose to eat up to half their meals without meat, and a further twenty-one per cent were planning to cut back on meat.[22] Environmentalists point out that a major proportion of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the meat and dairy industries.[23] Most people now want to ban intensive farming; back in 1995 a survey found that seventy-seven per cent of people were opposed to battery hen cages.[24] Our relationship towards animals is becoming more thoughtful.

The experiences of the vegetarians and animal rights activists who worked for and dreamed of a non-violent society have remained largely untold. Historians and statisticians have tended to ignore meatless diets, and it is especially difficult to uncover the lives of working-class vegetarians and vegetarian people of colour. Yet the history of our communities includes the stories of the vegetarians, pacifists, and socialists, as well as those of the meat companies, soldiers, and capitalists. The gentle voices deserve a hearing, as well as the strident ones. Primarily, this is the tale of a handful of courageous idealists who spoke out against cruelty and injustice, and were not afraid to defy convention. Although their impact on our communities is difficult to assess, they were brave and inspiring figures, many of whom did their utmost to create a more compassionate world for all living beings. They still set an example for us today.

1. A fig for the vegetarians!

James is about to part with, dispose of or let his cows.

having nothing but horses...! am not sorry for this change

since his wife sets so inordinate a value on mere animal

life that she would think herselfguilty of a crime were she

accessory to the death of a chicken.She is a dear, sweet,

loveable creature, sensible & cultivated with everything to

recommend her but this compassion run riot.

—Jane Maria Atkinson, 4 September, 1859.[25]

On a grey July evening in 1857, the Kenilworth approached the Taranaki coastline, bringing a group of English settlers, among them Mary and James Richmond, to the small town of New Plymouth.[26] It had been a protracted voyage—122 days, and two deaths, between Gravesend and Auckland. James’ family waited on the shore to welcome the young couple as they disembarked, and soon the group started for home along one and a half miles of muddy road to the family’s land at Merton. The winter night was moonlit, yet showery, and as Mary approached her new home, a rainstorm pelted down.[27] She thought about her sisters and mother, half a world away, and felt the weight of separation. Her ‘dearest ones may be in sorrow or danger, lying seriously ill, perhaps dying & yet that for months one can know nothing of it—do nothing to help or comfort them.’[28]

The travellers arrived at a cluster of cottages, the homes of James’ extended family, and Mary and James settled into ‘Bird’s Nest,’ a one-room hut jutting from a roughly cleared paddock studded with large blackened tree stumps. Here Mary learned to cook meals in vast iron pots, and worried that her husband’s farm raised cows and pigs for slaughter. At twenty-three, Mary was an ethical vegetarian, who was horrified that ‘animal life has to be sacrificed by men...for their own sustenance.’ Deeply religious, she was sometimes stricken by doubt, as she thought about the ultimate fate of the cows and pigs. The degree of suffering in the universe implied that ‘things must have got a twist’ and life was not moving in harmony with the will of God.[29]

Friends and family perceived the will of God quite differently, however. Around Christmas 1859, Richmond opened her mail to fi nd a long and closely argued letter from her sister in London. Annie Smith was anxious about her sister’s vegetarian diet, especially now that Richmond was pregnant, and had consulted a family doctor on her behalf:{1}

‘I thought it would be well Mary dearest to ask Dr. Kidd how vegetarianism was likely to agree, thinking perhaps his opinion might have some weight with you (on the physical side of the question). He remembered you and your constitution quite well. He said he thought it would be very injurious to you & injure your constitution & your child’s very much...I had no idea he would speak so strongly. He said that you should not on any account persevere in it.’[30]

Vegetarians in nineteenth century New Zealand faced intense pressure to shut up and eat up. The tens of thousands of migrants that arrived on New Zealand shores in the nineteenth century were largely from Britain, and British culture shaped colonial views of meat and vegetarianism.[31] Animal products were nutritious, delicious and signified wealth and power. Meat was ‘a marker of prosperity and status, of being one’s own master.’[32] As well as eating animals, people wore them—in the 1880s, one woman returned from Europe with a reception gown ‘that must have 200 little brown birds fastening a rose-coloured crepe upon a skirt of white silk.’[33] With the advent of refrigerated ships in the 1880s, and the dispatch of vast numbers of icy sheep carcasses to Britain, animal flesh assumed a central role economically as well as gastronomically. Vegetarianism seemed eccentric, extreme, and possibly unpatriotic.

Nonetheless, the growing vegetarian movement in Britain influenced New Zealand. Ships set off for New Zealand, bringing ideas in the form of newspapers, books, letters; they also carried vegetarian settlers. Occasionally overseas lecturers toured the country, creating debate about meatless diets, and persuading some New Zealanders to take a fresh look at what was on their plates.

Early Maori vegetarianism

Although this chapter focuses on British colonists, Maori certainly had traditions of vegetarianism. According to the oral literature of the peoples of Te Tai Rawhiti (the East Coast), the ancestor Toi-kai-rakau (Toi the wood-eater) was a vegetarian. Ngati Awa retell the story:

‘Twelve generations from Tiwakawaka came the ancestor Toi te Huatahi. Toi resided at Kaputerangi Pa which is located above the Koohi Point Scenic Reserve. On the arrival of Hoaki and Taukata to the area in search of their sister, Kanioro, they were treated to a feast consisting of fern root, berries, and other forest foods. Upon tasting these foods they took an instant dislike to them, remarking that it was just like eating wood. It was from this event that Toi became known as Toi-kai-rakau (Toi the vegetarian). Hoaki and Taukata asked for a bowl of water in which they added dried preserved kumara or kao and asked their hosts to taste it. Having tasted this delicious kai they desired to have more of it.’ [34]

The nineteenth century Pakeha scholar Elsdon Best reported that Maori tohunga used a vegetarian diet to treat diseases such as ngerengere (leprosy):

‘The Maoris [sic] endeavoured to cure the disease by keeping the leper from sunrise to sunset in a vapour bath. During the process of steaming, the tohunga (priest-physician) repeated the karakia and charms especially applicable to such a malady. The diet during treatment was entirely vegetarian, no fish or pork being allowed.’ [35]

Vegetarian traditions continue today among Maori. Early in 2013, the Tuhoe political activist and leader Taame Iti (whose son is named Toi-kai-rakau) announced his preference for vegan food on his release from jail. [36]

Meat and class in Britain

Knowing a little about food and society in nineteenth century Britain can help us understand why European settlers, both rich and poor, prized meat so highly. Prosperous British people chewed through copious quantities of flesh. Meat-eating was ‘central to [British] society, and, especially for the middle classes, as a sign of social affluence...The vegetarian could hardly even begin to erase this symbol of power and wealth.’[37] Isabella Beeton’s extremely popular Book of Household Management (1861) suggested ‘plain family dinners’ of boiled turbot and oyster sauce, roast leg of pork, roast haunch of mutton, boiled neck of mutton, ribs of beef, or rump-steak pudding.[38] The ‘comfortable meal, called breakfast’ was even more of a feast, if possible one should set a sideboard with dishes of cold tongue, veal and ham pies, broiled sheep’s kidneys, grilled whiting or haddock, cold joints of game and mutton chops.[39] Amid all the plates of meat, fresh vegetables were noticeably absent. Raw vegetables, Beeton warned, ‘are apt to ferment on the stomach.’[40] Tomatoes should only be eaten stewed, and one should be wary of them, as ‘the whole plant has a disagreeable odour, and its juice, subjected to the action of the fire, emits a vapour so powerful as to cause vertigo and vomiting.’[41]

Working class British people ate little meat, but not by choice. Many people were nearly starving. A doctor gave evidence in 1843 to a government commission that ‘four out of five working people who consulted him were really suffering from malnutrition and their medical problems would be resolved if they ate decently and regularly.’[42] The journalist and former labourer William Cobbett described English peasants as ‘the worst used labouring people on the face of the earth. Dogs and hogs are treated with more civility, and as to food and lodging, how gladly would the labourers change with them.’[43] Factory workers in the cities suffered desperate hardship, and people occasionally collapsed from starvation in the London streets.[44] Where people endured such poverty, deliberately rejecting any kind of food would have seemed puzzling.

Some working people sought to escape from hunger and hardship by moving overseas in the hope of a new life. Shipping and emigration companies produced booklets and posters encouraging workers to migrate overseas to other parts of the Empire. New Zealand was portrayed as a land of milk and honey, and thousands of British settlers arrived in the nineteenth century in search of a better way of living.[45] The military surgeon and author Arthur Thomson wrote in 1859 that ‘England has no future for most of the present generation...the working man from the cradle to the grave lives little above starvation and has nothing to hope for, whereas in New Zealand there is a great future for him.’[46]

Abundant New Zealand

Prime joints of roast lamb and beef were central to this ‘great future.’ Although company propaganda about New Zealand was often misleading, it was true enough that food was cheap and plentiful. When labourers wrote back home to England, the satisfaction of fi ne roasts, steaks, and chops shines through in their letters.[47] Visiting union official Christopher Holloway praised the living conditions at an Oamaru sheep ranch in the 1870s. He observed:

‘some 40 men set down to as good substantial a dinner as one could desire. There was roast beef, vegetables, and plum duff. I was told that the men get beef or mutton 3 times a day, and plum duff 4 times a week—the employers here say that if a man is to work well, he must live well.’[48]

Some working people were excited to get the chance to go hunting, an upper class sport in Britain. John Gregory, a Wellington resident, wrote that:

‘If you go into the bush about three miles you can have plenty of pork for shooting but you must have a good dog and gun. There are plenty of wild bulls, it is the best of beef; there is no one to say they are mine; those that get them have them.’[49]

Cheap and tender meat also appealed to well-bred ladies and gentlemen. Lady Mary Anne Barker enthused that ‘there is no place in the world where you can live so cheaply and so well as a New Zealand sheep station.’[50] At her farm in the foothills of the Southern Alps the family dined on:

‘Porridge for breakfast with new milk and cream a discretion; to follow mutton chops, mutton ham or mutton curry, or broiled mutton and mushrooms, not shabby little fragments of meat broiled, but beautiful tender steaks off the leg; tea or coffee and bread and butter, with as many new-laid eggs as we choose to consume. Then for dinner at half past one we have soup, a joint, vegetables and a pudding, with whipped cream.We have supper about seven, but this is a moveable feast consisting of tea again, mutton cooked in some form of entree, eggs, bread and butter, and a cake of my manufacture.’[51]

Stupendous quantities of meat were prepared for celebrations. In 1857, the vegetarian Mary Richmond joined her husband’s extended family for a shared Christmas dinner at their home near New Plymouth. A summer downpour rendered outdoor dining impossible, so eighteen family members squeezed into the living room to feast at a makeshift table of kauri boards laden with turkey, ham, beef pies, and five roast chickens. A sixteen pound boiled plum pudding and mince pies followed the main course, though both would have contained suet. There was little vegetarian food— Richmond had a choice of raisins, almonds, or gooseberry pie.[52]

‘Compassion run riot’

In 1850s Taranaki, Richmond was constantly nagged about her diet. Her sister-in-law Maria was bewildered that Richmond cared so much for ‘mere animal life.’[53] Ten years older than Richmond, Maria felt herself much more experienced and sensible, and considered that the younger woman was ‘inclined a little to be morbid in some of her notions, owing to what in phrenological terms would be called an undue development of the organ of compassion.’[54] She urged her sister-in-law to begin eating meat again. Richmond’s husband, James, was a little more sympathetic; in December 1857 he sold the farm pigs to his brother Harry, appeasing Mary’s conscience somewhat. However, he kept the cows.[55]

Richmond was also badgered by friends and relations back in England. Family friend and Spectator editor Richard Holt Hutton became worried that Richmond might waste away. In March 1878 he announced his intention to: ‘inveigh against her on Mauritian{2} principles for this vegetarian notion. She is a sweet creature, and I would not willingly see her health fail from any reverence for cows and sheep. I don’t undervalue animal enjoyment—such as it is—but surely one of the highest things that animal life can effect, is to contribute to the health & strength of a higher order of beings.’[56]

He was wise enough to add that ‘I must not put it to her on this ground.’[57] Though Hutton strongly opposed animal experiments, his sympathy for animals did not extend to avoiding their flesh. He believed implicitly in ‘the clear law of physical health which requires animal food.’[58] At the time many experts believed that meat was essential for health. Doctors prescribed beef tea for invalids, and argued that herbivorous animals suffered from tuberculosis, and therefore ‘a person of consumptive tendency, who demands, above all things, easily digestible food (which vegetables, on the whole, are not) and a diet rich in fats, might develop the disease through rash experiments in vegetarianism.’[59] The French physician, E. Monin, argued that: ‘vegetable diet, owing to its introducing more mineral salts into blood than animal food, was the means of causing chalky degeneration of the arteries.’[60]

Richmond’s family in England were concerned about her soul as well as her body. Her sister Annie Smith worried that Richmond had a ‘spiritual disease.’[61] Smith wrote long letters to Richmond, arguing that vegetarianism was unchristian:

‘If you believe in the inherent sinfulness of taking animal life, I don’t see how you can believe in a good Creator...animals are so evidently made to prey upon one another, besides their instincts who can look at a tiger or hawk...and doubt it. We cannot live without taking life, do what we will we kill animalcule [sic] in the water we drink.’[62]

Smith continued, ‘does not your belief make all creation sinful? how then can it be the work of a good God? Is it not far harder to believe this than to believe that taking animal life is not in itself a sin?’[63] Closer to home, her sister-in-law Maria continued to argue against vegetarianism. Eventually Richmond succumbed to Maria’s ‘kind urgency,’ agreeing to eat a little meat, at least while she was pregnant.[64]

Meanwhile, tensions over land were growing between Maori and Pakeha. Many Taranaki colonists hoped for a war that might grant them extra land. After Te Atiawa chief Wiremu Kingi Te Rangitake peacefully evicted a European survey party from his land, Governor McLean announced martial law.[65] On February 22nd, 1860, Major Murray declared war, and many European women and children left as refugees for safety in Nelson. Mary Richmond, seven months pregnant, travelled with them. She lived in the South Island for the rest of her brief life, giving birth to four more children. Exhausted after nursing three of her children through scarlet fever, she became ill herself and died in October 1865, at the age of thirty-one.[66]

Richmond’s vegetarianism may have had some influence on those around her. During her years in New Zealand she grew very close to Arthur Atkinson, her brother-in-law.[67] Some years after Richmond’s death Atkinson stopped eating meat. He adopted unusual eating patterns, consuming his main meal of the day at nine or ten o’clock at night, and washed down his vegetarian food with sour ale and soda.[68] Atkinson was nicknamed ‘Spider’ because of his passion for collecting spiders, and whenever possible, he locked himself away into his study, a ‘chaos of bottles, dusty books, cobwebs and wood ashes.’[69] Maria, his wife, complained about his bizarre food habits, commenting that ‘for fanatical faddism, there is no match for a true born Atkinson.’[70]

Vegetarianism in Britain and New Zealand

Mary Richmond’s ideals were shaped by the vegetarian movement overseas, especially in Britain. Much as meat was prized in nineteenth century British society, a curious phenomenon emerged early in the century—citizens who deliberately rejected meat. The term ‘vegetarian’ came into usage in the 1840s, and a Vegetarian Society formed in Ramsgate in 1847. In the early days the Vegetarian Society was largely an initiative of the Bible Christians, a sect inspired by Emanuel Swedenborg, a Christian mystic who believed that meat-eating signified the fall of man from divine grace.[71] Later vegetarians set up their own communities, such as Alcott House in Richmond, where the members were celibate, spent much of the day gardening, and followed a vegan diet for health, spiritual, and ethical reasons.[72]

Such ideas spread to New Zealand. Despite being separated by thousands of miles of sea from other parts of the Empire, settlers eagerly followed developments overseas. A wide selection of newspapers and magazines were shipped in; in Otago in the 1870s one could subscribe to papers ranging from the Illustrated London News to the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine.[73] In 1876 the telegraph arrived, an information revolution that allowed virtually instantaneous communication with the wider world.[74] According to the Wanganui Herald Newspaper Company, ‘a daily supply of well-selected telegraphic items is an absolute necessity.’[75] The quantities of data arriving by cable encompassed almost every imaginable topic, including meatless diets. Between 1850 and 1900, New Zealand newspapers published over two thousand articles mentioning vegetarianism or vegetarians.{3} These discussed food safety, health and animal rights, reported on the doings of famous vegetarians such as Thomas Edison and Leo Tolstoy, and cracked vegetarian jokes.[76] From at least 1882 onwards, one could buy imported vegetarian cookbooks.[77]

Diseased and dangerous flesh

There were certainly compelling reasons to think twice about eating meat. In 1898, a horrified journalist from the Marlborough Express inspected the carcasses of euthanised dairy cows in Whanganui:

‘Such a gruesome sight as was presented by the viscera of the cows destroyed was enough to turn even the strongest stomach, and to make one forswear beef and dairy produce forever, and, without single exception, tuberculosis, hydatids, actinomycosis [lumpy jaw], and other bovine diseases were plainly to be seen in the different organs affected.’[78]

Such reports tended to put vegetarianism into a more favourable light. There was no national system of meat inspection in the nineteenth century, and people imagined that they might contract cancer or tuberculosis from eating sick animals.[79] The British dietary reformer Thomas Allinson painted a grisly picture of the consequences of eating meat:

‘Flesh may contain parasites, and so give rise to tapeworms or trichinae; or it may be diseased and cause consumption or malignant pustule [sic], and other dreadful complaints or it may fl ood our system with nitrogenous waste, and start off gout, rheumatism, stone [sic] in the gall bladder, in the kidney, or in the urinary bladder or cause indigestion, biliousness, stomach or liver trouble, etc.’[80]

In 1894 Mayor Henry Fish of Dunedin personally examined local butcher shops. To his horror he discovered ‘patches of hydatids and cysts’ in the mutton for sale.[81] An unhappy restaurant patron was disgusted to find a ‘tubercular deposit’ in a leg of mutton while dining out:

‘We all are aware that the poison of tuberculosis is easily transmitted by animal food to human beings, giving rise to a bad form of consumption; and the evil does not remain in the individual using the diseased meat, for if he be a married man it is transmitted to his offspring.’[82]

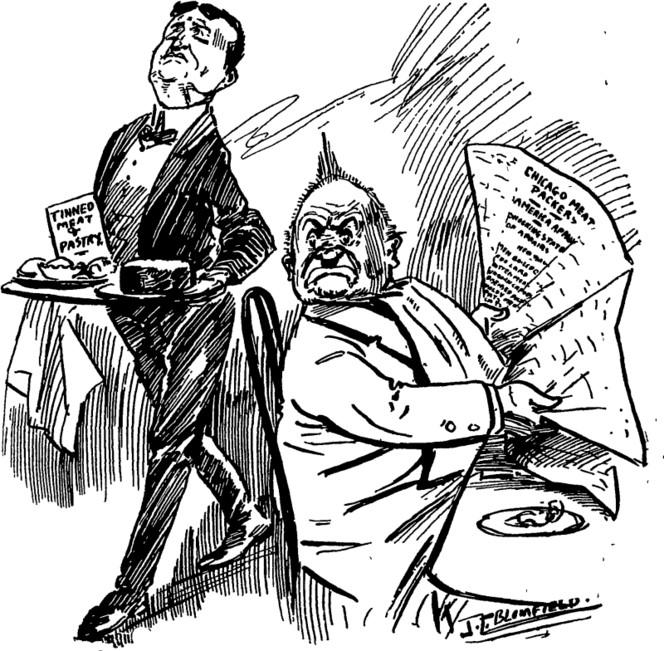

Novelists drew further attention to the meat industry. In 1906 Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle appeared on the shelves of New Zealand bookstores. Sinclair’s book described the experiences of workers in a Chicago slaughterhouse, using the treatment of animals as a metaphor for the fate of working class people under capitalism. Inadvertently, he influenced people all over the Western world to stop eating meat. As the Otago Witness put it, ‘many people are wondering, since they have read the horrors recited in its pages, what unutterable horrors they have literally been swallowing.’[83] There were calls for a commission to investigate the meat trade. The Bush Advocate described ‘unborn calves taken from the carcasses of dead and sometimes diseased cattle, and used as sausages’ and cases where inspectors had accepted bribes for passing cattle that should have been condemned.[84]

Some readers demanded stricter regulations, or even stopped eating meat. In the early 1850s James Boylan, an Auckland councillor, visited a slaughterhouse. He was so appalled that he turned vegetarian, fearing that he might catch cholera from the diseased flesh.[85] However, improvements were slow. Forty years later, the Grey River Argus was complaining about the large numbers of tubercular cattle sent to slaughterhouses, commenting sardonically that ‘it will be no wonder if the people up here swear off meat and milk altogether and take to beer and vegetarianism. One does not know how much cancer and consumption may be packed away in the succulent sausage.’[86]

Refrigeration and the economy

Such reports must have made anxious reading for New Zealand farmers, who were enjoying the profits of the frozen mutton trade. Up until the 1880s, wool and wheat were New Zealand’s main agricultural exports. However, in the late nineteenth century, new refrigeration technology meant that it was practical for farmers to ship frozen meat to the northern hemisphere. The first shipment of five thousand frozen sheep carcasses left from Port Chalmers in March 1882, and was sold in Britain for sixpence a pound, a high price at the time. The North Otago Times predicted:

‘the inauguration of a new commercial era...placing at the disposal of New Zealand stockowners “the potentiality of growing rich beyond the dreams of avarice.” With a sure market to which it can be sent with the certainty of obtaining a good price, it is no exaggeration to say that this country could produce twenty times as much meat and dairy produce as it now produces.’[87]

The journalist was perceptive; over subsequent decades New Zealand agriculture reshaped itself to ship huge numbers of frozen sheep and cows overseas. As the meat export industry expanded, the very idea of New Zealand became associated with frozen meat. Refrigeration lead to ‘revolutionary developments not merely in the economy but in New Zealand culture.’[88] Eating meat was not just about enjoying local produce; it became one’s civic duty. In 1897, an Otago Daily Times columnist asked:

‘If all the world becomes vegetarian, or if at least Christendom... what is to become of our frozen meat trade? I take it that it is every patriotic New Zealander’s duty not only to eat meat himself, but to encourage the use of it by others. A fig for the vegetarians!’[89]

Eating our friends

Even as New Zealanders sent thousands of frozen animal bodies overseas, we worried about the welfare of domestic animals. New Zealand has a long history of compassion towards animals. According to Maori worldviews, animals are viewed as taonga, or treasures. They are beings with intrinsic value. Everything in the cosmos is interconnected—birds, trees, fish, people, the elements.[90] Humans and animals have a shared genealogy. Before going on a fishing expedition, one recites prayers to Tangaroa, the guardian of fishes, and the first fish caught may be given back to the sea.[91] In the nineteenth century, Maori concern about animal welfare took new forms, as King Tawhiao’s Kingitanga parliament passed laws forbidding cruelty to animals.[92] When Pakeha arrived in New Zealand, they brought British traditions of sentiment towards domestic animals, especially cats, dogs and horses. The first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty To Animals (SPCA) was set up in Canterbury in 1872, and others formed around the country. [93]

How did this all sit with New Zealand as a meat-eating, meat-exporting country? Unfortunately, some early SPCAs did little for animals. In June 1886, a critical SPCA committee report concluded that the Wellington SPCA ‘had been more interested in elevating homo sapiens than protecting animals from our species; more concerned with becoming a great nation.than with the welfare of poor dumb beasts.’[94] There was also the contradiction that many SPCA members condemned cruelty to animals while also munching on them. In March 1898 there was a lively debate in the pages of the Otago Daily Times on this subject. ‘An Animal Lover,’ asked rhetorically:

‘How can the animals be treated with kindness when they are slaughtered by thousands, ruthlessly overdriven on their way to the slaughter yards and made to suffer nameless tortures while there, at the hands of butchers heart-hardened by custom, before they are ready for the tables of the members of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals?’[95]

The unknown writer asserted that animals were of value in themselves. They were not simply tools for humans:

‘Judging by the tone of our newspapers one would almost think that to serve as food for us is the chief reason for the life of the brute crealion...In God’s name don’t preach kindness to animals and then sanction and encourage the brutalities of the slaughter yard by going straight to a meal of flesh.’[96]

Then the debate erupted. Otago Daily Times columnist ‘Civis’ retorted that farmers were less cruel than nature:

‘Would it not be more cruel to permit animals to multiply indefinitely and hark back to the laws of nature? If the animals are left, to the operation of the law which ordains that the fittest shall survive, what cruelties must be inflicted on the weaker.Most of us would step aside rather than tread on a worm; some would even open the window that a fly should escape; but we must stop at the ridiculously absurd.’[97]

Others weighed in on the side of the animals. ‘Purun Dass’ praised the original letter, agreeing that ‘cruelty to our helpless-fellow creatures is the entirely logical result of the belief that they have been created wholly and solely for our use.’[98] A few days later, ‘An Animal Lover’ had the last word, countering that while nature could indeed be cruel, this did not justify the human exploitation of animals, or the breeding of vast numbers of sheep, cattle and game purely to be killed. ‘A non-flesh diet,’ he or she concluded, ‘would not put an end to all cruelty to animals but it would be a very good beginning.’[99]

Meanwhile, the novelist Samuel Butler, a former Canterbury sheep farmer, was also pondering animal rights. Although no vegetarian, he explored the ethics of eating animals in the 1901 revision of his novel Erewhon. In Butler’s ambiguous utopia, a prophet proclaims that it is wrong to kill animals for food and ‘stringent laws were passed, forbidding the use of meat in any form or shape, and permitting no food but grain, fruits, and vegetables to be sold in shops and markets.’[100] However, the debate is reduced to absurdities, when a botanist argues that plants also have intelligence and souls. Only fallen fruit and leaves can be eaten with a clear conscience. Eventually an oracle declares that people should ‘Eat or be eaten, Be killed or kill; Choose which you will,’ and the country reverted to meat-eating.[101]

Others also felt that vegetarianism was impractical. In 1897 the Hawke’s Bay Herald criticised the arguments presented at a vegetarian conference in England. The journalist tried to pick apart the contention that the ‘sacrifice of animal life for any purpose is wrong, and even criminal,’ arguing that it was vegetarianism that was wrong. Vegetarian ideals would even destroy civilised society:

‘How would the squatters of Australia deal with the rabbit plague if such a doctrine obtained acceptance? Kittens and puppies would never be drowned, but permitted to multiply without stint. It is difficult to say whether any vegetarian has ever meditated on the condition of a country in which no animals would be killed for food or sport or clothing. Cattle breeding would be ruined, and the butcher spiritualised out of existence.’[102]

Recipes and cookery books

Vegetarians unconvinced by such arguments may have had a tough time finding suitable recipes. Popular cookbooks such as Isabella Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861) would have been little help. By the 1890s, however, some booksellers were importing cookbooks such as Mrs E.W. Bowditch’s New Vegetarian Dishes; Vegetarian Cookery, by a Lady; and Cassell’s Vegetarian Cookery.[103] Newspapers occasionally published meatless recipes, though sometimes these were odd concoctions of cabbage or carrots that had been dreamed up to mock vegetarian cuisine.[104] However in 1891 the Bush Advocate printed a recipe for savoury pea-soup, ‘much liked by most vegetarians’:

‘Pea-soup (vegetarian) Soak one cup split-peas for 12 hours in cold water. Boil together, adding a little more water, so that it is not too thick. Add turnips, carrots, and onions, cut up (one carrot is sufficient), a little turnip-top, dried mint, celery, thyme, two or three tomatoes, pepper, salt, butter, and half a cup of rice, stirred in gradually. Simmer five hours stir frequently. Very good and nourishing for either adults or children.’[105]

Such recipes suggest some interest in vegetarianism. They also reflect the bland and stodgy cuisine popular at the turn of the previous century. One chomped one’s way through tomato and macaroni pie topped with hard-boiled eggs in white sauce, and vegetable Irish stew with parsnips, turnips and mushrooms, or fried potato rolls.[106] The veggie sausage has a long history. In 1905 the Auckland Star printed a recipe for ‘vegetable sausages’ of mashed carrot, parsnips and onions mixed with breadcrumbs and split peas.[107] They sound rather tasteless, though, to be fair, the addition of a ‘small piece of garlic’ was exotic and adventurous at the time.

Local cookbooks also included meatless recipes. St Andrew’s Cookery Book (1905) included several vegetarian soups.[108] However, there were just two salads: a beetroot dish, and an orange salad.[109] The 1908 edition of Whitcombe and Tombs’ Colonial Everyday Cookery, included a chapter of vegetarian recipes for dishes such as curried beans, vegetable marrow soup, and celery soufflé. The most sophisticated suggestion was ‘bananas as a vegetable’—green bananas should be roasted, or simmered Pasifika-style in milk, seasoned with salt and pepper.[110]

The Canterbury Dietetic Reform Association

In the early 1880 s a man identified only as Mr H. Satchell arrived from England to visit his son in Christchurch. He was one of several overseas visitors who helped raise the profile of vegetarianism in New Zealand. Satchell had been vegetarian for the previous two years, and believed that the change in diet had transformed his health. He and his son called a public meeting on January 16 th, 1882 at the Metropolitan Temperance Hotel. The elder Mr Satchell took the chair, advocating ‘the adoption of vegetarian principles as the only sure means by which the greatest of all blessings—good health—may be obtained.’[111] They found a name—the Canterbury Dietetic Reform Association—and made plans to distribute information on the ‘all-important’ subject of food reform.[112] Mr Satchell was optimistic that:

‘This young offshoot may...become the stalwart oak, and so rescue multitudes from an untimely grave, for there is much sickness. I think I am within the mark when I say that more than two thirds of the people are suffering in some degree from ill-health, while the rate of mortality among the children is very heavy.’[113]

It was true that disease was rife in Christchurch. In the 1870s, alarmingly high numbers of babies died, and there were epidemics of typhoid fever and diphtheria. However, inadequate sanitation was more likely than poor diet to be the cause. The only sewerage system was the two rivers, and wells were contaminated by seepage from cesspits. The Avon River was heavily polluted with household slops, sewage, and discharges from slaughterhouses, tanneries and tallow works.[114]

The Canterbury Dietetic Reform Association’s first meeting was reported around the country. The Christchurch Star gently satirised Satchell’s ‘unwavering faith in a purely vegetable diet’:

‘Who but a man of pluck and energy could possibly have taken the chair at such a meeting in this meat-raising, meat-devouring community? But, nevertheless, to the student of Shakespeare, proposals such as those of Mr Satchell are full of suspicious elements.Does not old John of Gaunt, “time honoured Lancaster” demand—almost with, his dying breath “and who abstains fron neat that is not gaunt?” Let these be startling warnings to those who nay perchance have had fleeting visions of naking a parsnip do the duty of the brave sirloin, of baking carrot tarts, and pricking toothsone garlic patties.’[115]

Little is known about the Canterbury )ietetic Reforn Association’s activities, and it soon lost its neeting venue as the Tenperance Hotel closed down in 1885. However Satchell junior later noved to Sydney, where he becane president of the New South Wales Vegetarian Society.[116]

Blasphemous vegetarianism

It is unclear whether the Canterbury )ietetic Reforn Association was still neeting when the controversial freethinking lecturer George Chainey toured New Zealand in 1887. Originally fron Essex, in England, Chainey had trained as a ninister in his youth, and eventually becane pastor of the Unitarian Church in Evansville, Indiana. Unitarians follow no set dogna, and the Evansville worshippers listened tolerantly to the ‘liberal, even radical’ ideas in his sernons.[117] However, Chainey’s beliefs becane steadily nore controversial. He studied )arwin’s theories of evolution and John Tyndall’s argunents for the separation of religion and science. On April 18th, 1880, he announced to his startled congregation that ‘he was not a Christian, that he would not pray, that he despised the conventional idea of Jesus, and wanted the hymnbooks sold for wastepaper.’[118] He offered his resignation, generating ‘a decided sensation and a great division of sentiment.’[119] Perhaps unsurprisingly, he had to leave the church, and turned to public lectures and writing to support himself.

Chainey drew large audiences to his lectures on topics such as ‘Does death end all?’ and ‘The Clergy, or, the Priest and Prophet.’[120] In an era before films and television, public lectures were a popular form of entertainment. For six pence one could book a seat in Wellington’s Opera House and listen to the latest speakers discussing subjects such as ‘Homes and Haunts of Jesus’ or ‘Physiognomy: the Art of Character Reading.’[121] Chainey’s unusual religious beliefs seem to have passed unchallenged. However, in meat-exporting New Zealand, his vegetarianism was a more disturbing heresy. In early August Chainey lectured on ‘Meat and Morality’ in Dunedin, criticising parents who fed meat to children. Newspaper reports suggest that he believed that eating meat led to bad behaviour. ‘If children consumed meat largely, the animal tendencies would not be kept down although the Bible were read in the schools every day in the year.’[122] His arguments would sound strange to vegetarians today, particularly the pejorative use of the phrase ‘animal tendencies.’

Otago farmers were outraged by Chainey’s condemnation of meateating. A Taieri farmer ‘Thomas Woolie’ lampooned the notion that ‘mutton gives the boys animal tendencies...our Sam’s tendens are awl right.’[123] According to the Otago Witness:

‘the bare mention in a mutton and beef-growing country of such doctrines is, it appears, flat blasphemy.Advocacy of the disuse of animal food is not profitable in Dunedin. We would rather pay to hear a lecturer who could explain how to bring about a rise in frozen mutton.’[124]

Escaping from the south of the country after a court appearance for unpaid bills, Chainey found more tolerant listeners in Wellington. On November 13th, 1887, he spoke at Wellington’s newly opened Te Aro Theatre and Opera House. Here a large audience waited to hear the professor describe his impressions of New Zealand. Chainey praised the lovely forms of the land, but criticised ‘the universal prevalence of meat diet,’ regretting that ‘the prosperity of the colony depends so largely upon its trade in meat.’[125]

May Yates and food reform

May Yates of the London Vegetarian Society received more sympathy when she argued for vegetarian diets in 1894. Officially, Yates had been invited to lecture on the advantages of ‘a world-wide confederation of the English speaking race, including the improved cultivation of the land, cooperation, and the abolition of sweating and insanitary dwellings.’[126] However, she took the opportunity to argue that ‘colonists consume too much meat, and would be all the better for a change of diet.’[127]

Yates had been a health food advocate for years. Born as Mary Ann Yates Corkling (her father objected to her dragging the family name into the public arena), she became convinced of the benefits of a plant-based diet after a visit to Sicily, where she noticed that the local labourers were splendid physical specimen. In an interview with Christchurch’s Star, she explained that:

‘I was struck with the sturdy, healthy appearance of the peasantry, and with the large amount of hard work they do upon a diet of wholemeal bread, haricot beans, macaroni, fruit, olive oil and milk. I was especially impressed with the value of wholemeal bread as an article of food.’[128]

Back in London, she started a campaign to make brown bread more available to working class people. In 1850 she formed the Bread and Food Reform League, and worked with the English Vegetarian Society to provide London school children with half penny meals. These consisted of a pint of thick vegetable soup, with wholemeal bread, and currant slices.[129] Her interest in vegetarianism grew, and she was appointed as organising secretary of the London Vegetarian Society in 1890.{4}

Yates arrived in New Zealand at a time of ongoing concern about meat safety. Her argument that vegetarianism was a more wholesome choice than eating animals ‘suffering from ulcerating and granulating wounds’ fell on receptive ears.[130] Eating meat was also ‘opposed to the highest ideal of humanity, which is horrified at the thought of our daily food being associated with the bloodshed, cruelty, and death inseparably connected with the slaughter-house.’[131] She circulated a pamphlet listing twelve reasons to turn vegetarian. In a Christchurch lecture, she praised the nutritional value of

Yates’ twelve reasons for vegetarianism

1. Eminent scientists are of the opinion that the internal and external structure of man clearly indicates his adaptation to a frugivorous diet.

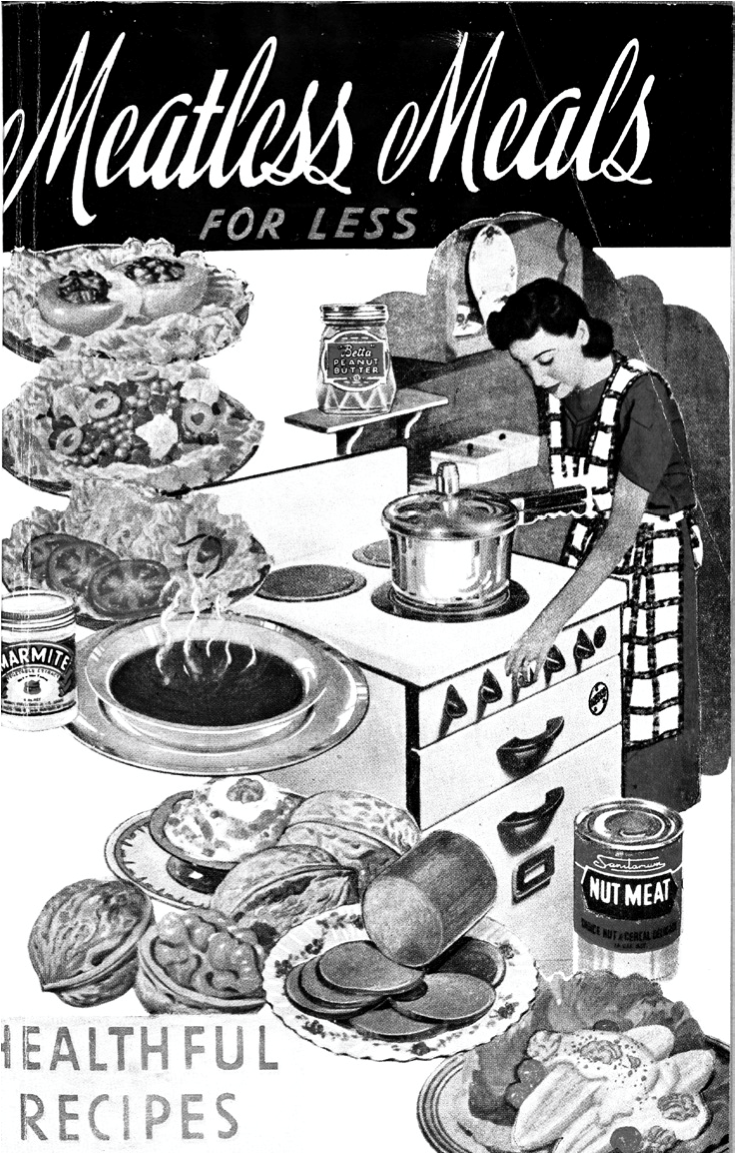

2. Flesh meat contains nothing of value which may not be obtained from the vegetable kingdom.

3. The process of waste and repair constantly going on in the living system renders it impossible for flesh to be free of impurities.

4. Good authorities say that eight out of ten of the animals slaughtered for the public market are diseased, caused by immature breeding, etc., in order to fatten them and prepare them for sale.

5. Vegetarians enjoy comparative immunity from disease.

6. Observation and evidence of medical men who have given special attention to the cause and cure of the drink crave, prove that the desire for intoxicants is reduced in proportion to the abstinence from flesh meat.

7. The primitive injunction from God to man at the creation, as contained in Gen. i.29.

8. Beauty, as evinced by the women of the lower ranks in Ireland, whose diet consists chiefly of potatoes and milk.

9. The degrading influence of [the] butchering trade.

10. Land cultivated for grains, fruits, etc., employs more men than that used for grazing purposes.

11. Expense. Meat contains from 50 to 70 per cent of water, while pulse and grains contain but 14 per cent.

12. Muscular power, physical energy, and endurance. The Spartans were vegetarian, as well as the armies of Greece and Rome, at the time of their conquest. Athletes of ancient Greece, when training for public games, invariably adopted a vegetable diet.[132]

her beloved wholemeal bread, and recommended nuts, as ‘especially valuable for their oil.’[133]

Initially, she met with some sceptical responses from those who:

‘did not want to be told by a woman that they must not eat so much of their favourite mutton; why, if bread and vegetables were to be made to take the place of mutton, what on earth would become of our frozen meat trade? Bother the woman we don’t want her doctrine of vegetarianism.’[134]

However, the Auckland Star praised Yates’ ‘plain, common-sense manner,’ and agreed that it would be beneficial for New Zealanders to consume more fresh fruit and vegetables.[135] Letters of support began appearing in the papers, acknowledging that: ‘as a rule, we eat too much meat in the colonies...Cancer is such an awful disease that one feels one would like to give up meat altogether.’[136]

Yates had the social status to make vegetarian ideas seem respectable; she was a wealthy, well-educated woman from an upper-class British family, and her social circle included politicians and aristocrats.[137] In New Zealand, she met rich and powerful figures, some of whom were sympathetic to her ideas about diet. Just before Yates returned to England, Wellington friends organised a banquet in her honour at the four-storey Trocadero Private Hotel in Willis Street. It was a dainty affair, attended by prominent citizens such as the former Evening Post editor David Luckie who welcomed the guests, reading a letter of apology from Sir Robert Stout, who had hoped to preside over the dinner, but was delayed in the South Island.[138] Mr. Cimino’s string quartet performed, and the thirty-five guests examined a menu of over thirty dishes. This was entirely in French, so that a dish such as cauliflower in white sauce was listed as ‘Choux fleurs a la Bechamel.’ Some diners were mystified:

‘Individuals could be seen in earnest consultation with their better informed neighbours, or, failing success there, with the waiters, and one old gentleman, who evidently desired to proceed warily for his stomach’s sake, produced a note-book, and before each course solemnly asked the waiter to explain to him the genesis of the dish, and elaborately wrote down the information thus obtained, and laid it beside him for reference before venturing upon the mystery.’[139]

Flattering reviews appeared in many newspapers. Described as a ‘sumptuous repast,’ it was ‘excellently served, and showed how much can be accomplished with vegetable resources alone’[140]{5}

After the main course, Luckie stood up to compliment the food. He explained that though he himself was ‘neither vegetarian, total abstainer, nor anti-tobacconist.much too much animal food was used by colonials, and especially was too much meat given to children.’[141] May Yates also spoke, praising the kindness and hospitality of everyone she had met. However, she:

‘greatly regretted that so much of New Zealand was given up to the raising of meat, and comparatively so little to the raising of fruit, which she contended would give much greater profit. She had seen an orchard of five acres in New Zealand realising £400 a year; lemon trees five years old producing £1 each per annum, and walnut trees producing £10 to £17 worth of nuts annually.’[142]

Yates left New Zealand a few days afterwards, but her visit had raised awareness of meatless diets. In December 1894, the Auckland Food Reform League began planning vegetarian picnics, though a sceptical reporter from the Observer preferred a banquet:

‘Picnic lunches are usually cold. Has the A.F.R.L. the temerity to think of a cold vegetarian lunch? Surely this would be inadvisable. It would require a very enthusiastic vegetarian to fortify the inner man with cold cabbage and cold boiled potato sandwiches. Far better would it be to give a vegetarian banquet and do the thing properly.’[143]

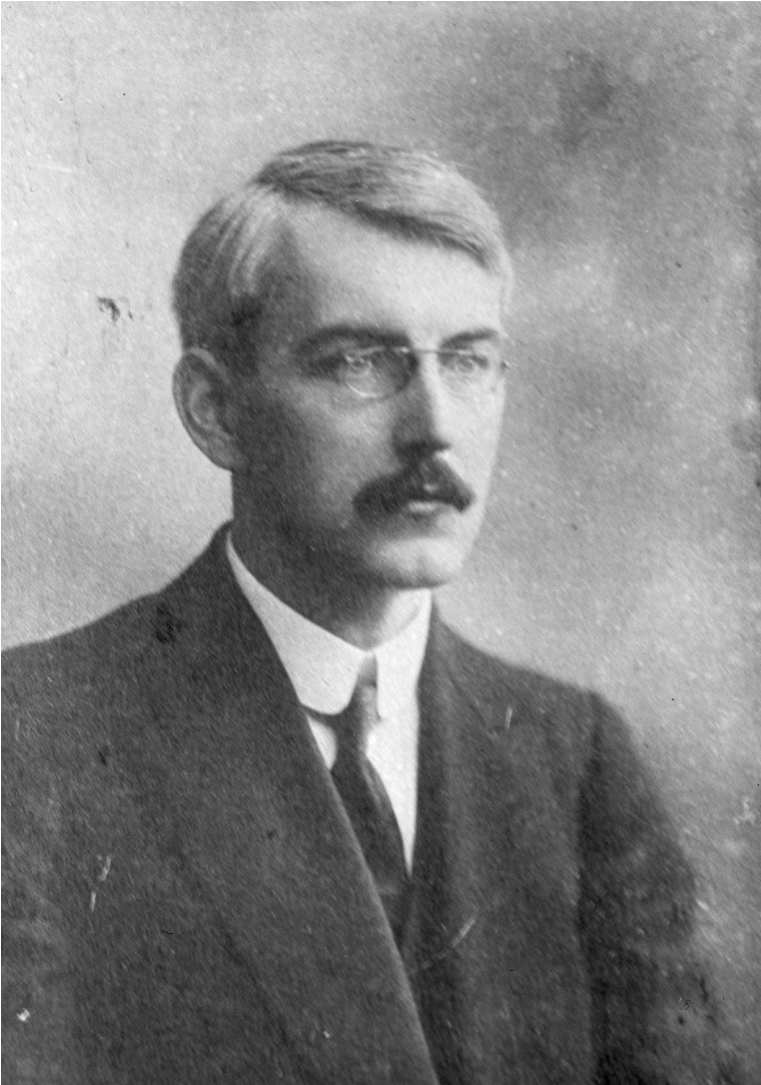

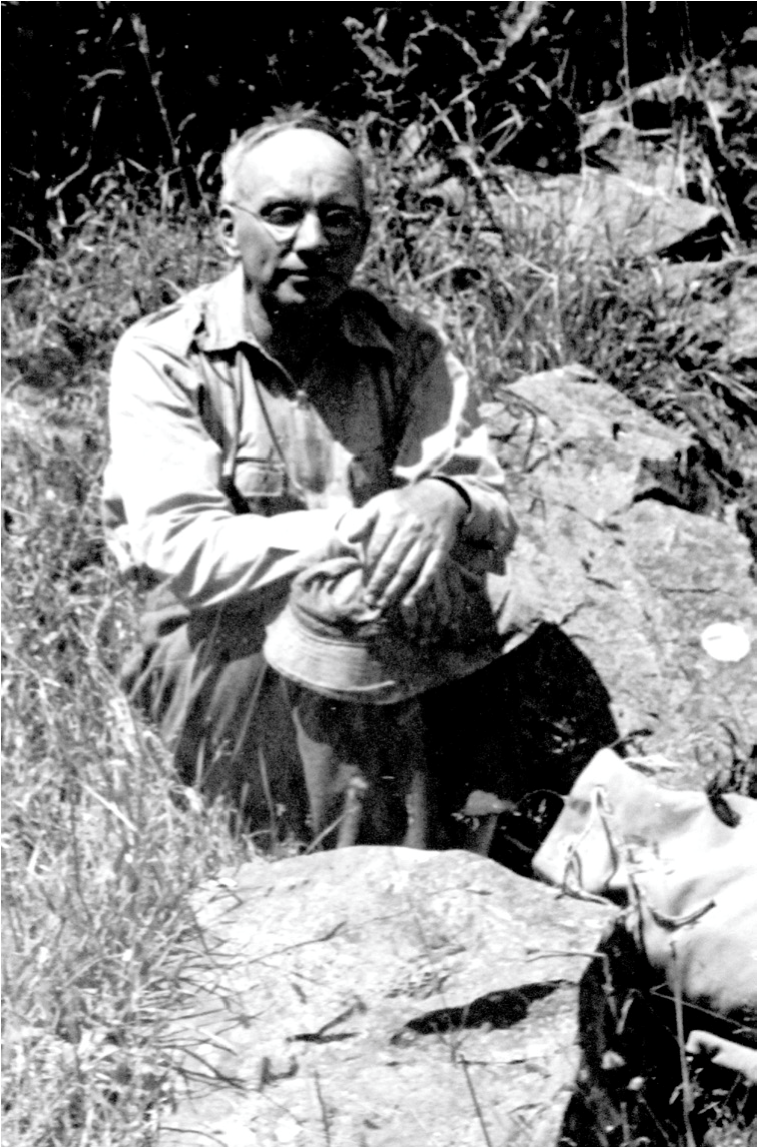

Harold Williams and vegetarianism in the 1890s

Whether or not May Yates made many converts is unclear. However the vegetarian arguments appearing in magazines convinced at least one young New Zealander that ‘animal food is unnecessary.’[144] In the 1890 s Harold Williams, a Christchurch teenager, stopped eating meat after reading articles in the New Review and Nineteenth Century magazine.[145] Williams’ experiences were not unlike those of Mary Richmond, forty years earlier. He endured criticism, social disapproval, and sometimes inadequate food. Yet Williams was less isolated than Richmond. He had vegetarian friends, and also meat-eating friends who did their best to cook tasty meals for him. Unlike Richmond, whose concern was chiefly for animal suffering, Williams came to vegetarianism in the course of a teenage exploration of political and social ideals.

Williams first decided to experiment with a meat-free diet around 1891 after reading ‘First Step,’ an article by Tolstoy in the New Review.[146] The Russian novelist argued that an ethical, Christian life was incompatible with eating animal flesh:

‘Once, when walking from Moscow, I was offered a lift by some carters who were going from Serpouhof to a neighbouring forest to fetch wood...On entering a village we saw a well-fed, naked, pink pig being dragged out of the first yard to be slaughtered. It squealed in a dreadful voice, resembling the shriek of a man. Just as we were passing they began to kill it.When its squeals ceased the carter sighed heavily. “Do men really not have to answer for such things?” he said. So strong is man’s aversion to all killing. But by example, by encouraging greediness, by the assertion that God has allowed it, and, above all, by habit, people entirely lose this natural feeling.’[147]

Williams was also influenced by a piece by a nonagenarian minister of religion who attributed his long life to a vegetarian diet, and by an article by Walburga, Lady Paget in Nineteenth Century magazine.[148] Paget was appalled by the trucking of cattle to slaughterhouses, and concluded that it was wrong ‘to take life in order to feed one self, when there is plenty of other available food which will do just as well.’[149] At the age of fifteen or sixteen Williams decided to stop eating meat—a difficult choice for a young man still living in his parents’ home. As one settler commented, ‘from the average colonial menu meat is never absent, and the ordinary colonist consumes it in some form thrice, and often four times daily.’[150] Cn Williams’ first attempt he managed to remain steadfast for just six months before the ‘forces of the surrounding world’ crushed his resolve.[151] Just after his eighteenth birthday in April 1894, however, he embarked with more success on a meat-free diet, arguing that:

‘i) It is wrong to kill animals for food, not only on the animal’s account but also on the slaughterer’s.

ii) Animal food is unnecessary. All the nutrient qualities of animal food can be found in the vegetable kingdom.

iii) Animal food is unhealthy, and it is hard to conceive conditions under which it was produced so as to be nearly as healthy as the vegetarian food.

iv) Vegetarian diet if it does nothing else at least improves one’s temper. I speak from experience.’[152]

Social disapproval was the most difficult part of being vegetarian, and at times Williams’ desire to fit in almost persuaded him to start eating meat again.[153] Yet he remained steadfast, reflecting that his vegetarian identity was ‘no longer a series of resolutions, but a part of my nature.’[154]

Williams was accepted as a probationary Methodist minister in 1896, and spent the next two years preaching in Christchurch’s St Albans circuit. Here he met other vegetarians, such as Will and Jennie Lovell-Smith of Upper Riccarton. Will and Jennie and their children were interested in socialism, vegetarianism, and feminism. Williams often visited the Lovell-Smith family home in Upper Riccarton, entertaining the younger children with stories and Maori haka.{6} He discussed Tolstoy’s ideas with the older family members, and became close friends with Will’s vegetarian sister Lucy Smith, and his vegetarian daughter Macie.[155] Williams wrote a four-page article describing his conversion to vegetarianism. This may have been New Zealand’s fi rst ever vegetarian poster—the Lovell-Smiths pinned it to the wall of the dining room where they crunched on their raw vegetables.[156]

Life became both less and more complicated once Williams moved away from Christchurch. In March 1898 he was sent to Waitara in the Taranaki District, where many of his days were spent tramping long distances over wet winter roads to visit his parishioners. Instead of discussing Tolstoy’s ideals, he made awkward conversation about the weather, farming, and cows. Sometimes there was no formal church for holding services. At Purangi he preached in a small galvanised iron shed, a former store, leaning against the counter, while his sixteen listeners balanced on boxes.[157] At least Williams had plenty of time for thinking. While cycling to visit his parishioners, he tried to work out his personal politics, concluding that:

‘I am beginning to hold Communism as part of my religious faith, and I must say that I am fast inclining towards Anarchism...sometimes there come to me moments of insight when it seems to me to be the only Christ-like, the only divine way to remedy the world’s evil to cast aside all fainthearted trust in violence, the weapon of evil, and to believe with all one’s heart in the spiritual power of love.’[158]

Willians’ superintendent, the Rev. W. G. Thomas was utterly baffled, unable to fathom ‘the problem [of] how a youth with such a heterodox library.can do the work of a Methodist minister.’[159]

Vegetarianisn was certainly a heterodox concept in rural Whanganui. Willians lodged with a local fanily, the Turners, but was too considerate to ask his hosts to prepare special neals. He sonetines went hungry, writing to a friend that ‘ny sernon on giving and receiving did not go well, because I had hardly had a breakfast.’[160] Mrs Turner had little idea of how to prepare a nutritious neat-free diet, and served up plates of narrow, punpkin, cabbage, and potatoes.[161] The potatoes were badly cooked, and for the rest of his life Willians loathed boiled potatoes. The cabbage nay have been little better. Popular cookbooks, such as the 1897 edition of Whitconbe and Tonbs’ Colonial Everyday Cookery advocated boiling cabbage and cauliflower for at least twenty to thirty ninutes. The authors advised adding a ‘piece of washing soda the size of a pea’ to prevent colour loss, or a piece of charcoal ‘to stop the objectionable snell.’[162]

However, other Taranaki folk tried hard to supply Willians with appetizing dishes. One kindly farner’s wife ferreted out that the young nan enjoyed brown bread, and she began experinenting with wholeneal flour. Unfortunately her attenpts net with little success; she produced a dense loaf that her husband ‘cruelly described’ as ‘a deep sea sinker.’[163] Williams did enjoy some tastier meals. The day after the brown bread debacle, he rode through mud and pouring rain to call on a young couple who ‘treated me to an appetising lunch of apple pie and scones and cream.’[164] Williams did not stay long in Taranaki. He was not a natural preacher; he suffered from a nervous stammer, and his ideas were too unconventional for his audience. After delivering a sermon in Inglewood, an elderly man came up to him and gently advised that ‘we are homely people here, and we like things plain.’[165] In Easter 1899 Williams left the Waitara circuit, abandoning the idea of a career in the Methodist church. He decided to study philology in Berlin, and in early 1900 he and his brother sailed for Europe on the Konigin Louise, bearing the addresses of two London vegetarian restaurants.{7}

A changing society

Perhaps Mary Richmond and Harold Williams lived a little too soon. Vegetarianism was slowly becoming more acceptable. Whitcombe and Tombs’ Colonial Everyday Cookery commented in 1908 that ‘the popularity of vegetarian cookery is on the increase...in large cities special restaurants are being opened to meet the demand.’[166] As the nineteenth century drew to a close, there was a ferment of new ideas across the British Empire:

‘The eighties and nineties witnessed a proliferation of cults and movements which promised to reorder a fragmented existence. Positivists and Socialists, theosophists and Spiritualists.even the more extreme adherents of vegetarianism and anti-vivisectionism, were participating in a common quest for a new unity amid the bewildering change of modern life.’[167]

Such ideas were woven through conversations that offered the possibility not just of different ways of eating, but of a different kind of society. In particular, it is a pity that Mary Richmond did not live longer, into a time where she could discuss the ethics of killing animals for food with sympathetic listeners, or banquet on asparagus and Italian-style pasta at the Trocadero Hotel. Or perhaps journey north through the kauri forests to Kaeo, a rural town just south of the Whangaroa harbour. Here one could shelter from the Northland sun under the veranda of Miriam Gibb’s general store, and share a glass of fruit juice with Christians who argued that God called his followers to adopt a meatless diet.

2. Perils of the flesh

Seventh Day Adventists and pure foods

The diet appointed man in the beginning did not include

animal food. Not till after the Flood,

when every green thing on the earth had been destroyed,

did man receive permission to eat flesh.

—U.S. Adventist leader Ellen White, 1905[168]

Today Kaeo is a tiny, impoverished rural town in Northland, and there are few clues that vegetarian Seventh Day Adventists once lived here. The main street of prim refurbished colonial buildings conceals a bleak history of poverty and unemployment. Many of those lucky enough to have a job work at the Sanford oyster-processing factory.[169] However, there is still a vegetarian centre of sorts in the far north. A short drive south of Kaitaia you will find Shangri-La, a valley of orchards, where vegan gardeners with names such as ‘Love’ and ‘Butterflies’ tend hundreds of organically grown fruit and nut trees: mandarins, oranges, avocados, pears, plums, nectarines, blueberries, macadamias, walnuts and almonds.[170] Birds, fish and invertebrates such as the giant snail Powelliphanta are the only carnivores around.

The term ‘vegan’ had not been coined in October 1885, when a small party of Europeans rowed up the tidal Kaeo river from the Whangaroa Harbour. The group included Stephen Haskell, an American Seventh Day Adventist preacher, who had arrived in Auckland just ten days earlier, on a mission to market The Bible Echo and Signs of the Times.[171] He was a vegetarian who considered that ‘the meats God created for food are fruits, grains, and nuts.’[172] For Haskell, health, compassion for animals, and the wrath of God were intertwined; he once wrote that ‘God has never forgotten to avenge the blood of animals slain for food. He uses various agencies to fulfil His word, as cancers, tumors, ulcers, consumption, etc.’[173] In Auckland Haskell stayed at a boarding house run by Edward Hare, and immediately got to work converting those around him, including his landlord.[174] Hare was so excited about his new faith that he invited Haskell to come and visit the Hare family in Kaeo, a town of three hundred people in the 1880s.[175]

The travellers went straight to Edward Hare’s family homestead, a pit sawn timber cottage at Kukupae, about a kilometre south of the main township. Here Haskell met Edward’s father Joseph Hare, Joseph’s second wife Hannah, and some of their numerous children. Haskell felt at ease with his hosts, observing with satisfaction that ‘only one of their number uses tobacco in any form, and all of them are temperate people.’[176] That evening, he preached to the family. After an all-night vigil of study and prayer, Joseph Hare decided to convert to the Adventist faith.[177] His family soon followed suit, adopting the Seventh Day Adventist principles of vegetarianism and abstinence from tobacco and alcohol.[178]

Adventism and vegetarianism

Steven Haskell and Edward Hare’s journey to Kaeo marks the arrival of the Seventh Day Adventist movement in New Zealand. It is also a milestone in vegetarian history. Haskell and other Adventist missionaries from Australia and the United States advocated a ‘hygienic’ or meatless diet, considering that ‘it was a religious duty for God’s people to care for their health and not violate the laws of life.’[179] Unlike many of the vegetarians in this book, Adventists tended to be socially and politically conservative, concerned about health and purity rather than animal rights or social justice. The Adventist faith derives from conservative evangelical Protestantism, and believers are guided by Old Testament dietary principles.[180] The church leader and visionary Ellen White taught that Adam and Eve followed a vegetarian diet in the Garden of Eden. Humans only started eating meat after the time of the Flood.[181] Vegetarianism was healthy and virtuous; it was the diet that God had initially planned for the human race. Eating pork was particularly sinful, because:

‘the tissues of the swine swarm with parasites. Of the swine God said, “It is unclean unto you: ye shall not eat of their flesh, nor touch their dead carcass.” Deuteronomy 14:8. This command was given because swine’s flesh is unfit for food. Swine are scavengers, and this is the only use they were intended to serve.’[182]

Adventist preachers such as Haskell recruited new believers and gently encouraged them to stop eating meat. This must have been an awkward message in New Zealand, as many families kept a pig to fatten in their garden plot, alongside chickens, and perhaps a cow.[183] Yet some were open to changing their diet. Edward Hare’s descendant Helen Smith describes Kaeo as the ‘vegetarian capital’ of New Zealand in the 1880s.[184] There were incentives to abstain, as a meat and alcohol-free lifestyle set one morally apart from one’s less puritanical neighbours. In Kaeo, hard drinking, meat-eating loggers and gum-diggers made up about a third of the town’s population. The Kaeo Hotel was closed for months in 1883 because of ‘drunkenness’, and when the Templar’s Lodge boarding house refused to sell beer, angry bush workers smashed all the windows.[185] For Adventists, meat was also diseased and unhealthy. The vegan Adventist doctor Daniel Kress argued:

‘Eat the food which is the purest and freest from disease, and take it in its purity, directly from the lap of mother Nature, not at second hand. The idea that we must feed these pure foods to animals and then eat them is erroneous. In some way people imagine they must shed blood and eat these lower creatures in order to be strong. The fact is the strongest and most useful animals we have feed on the natural products of the earth.’[186]

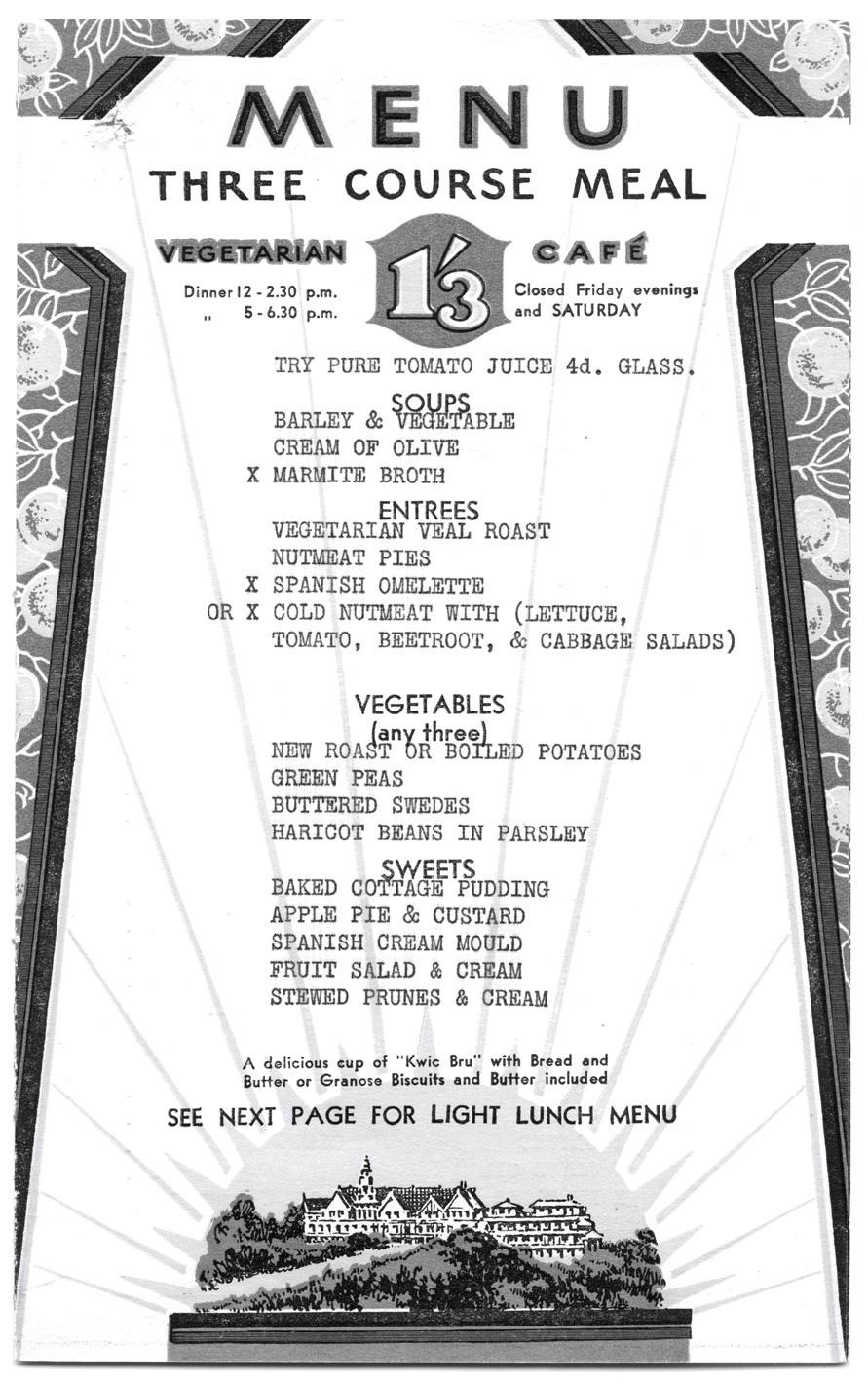

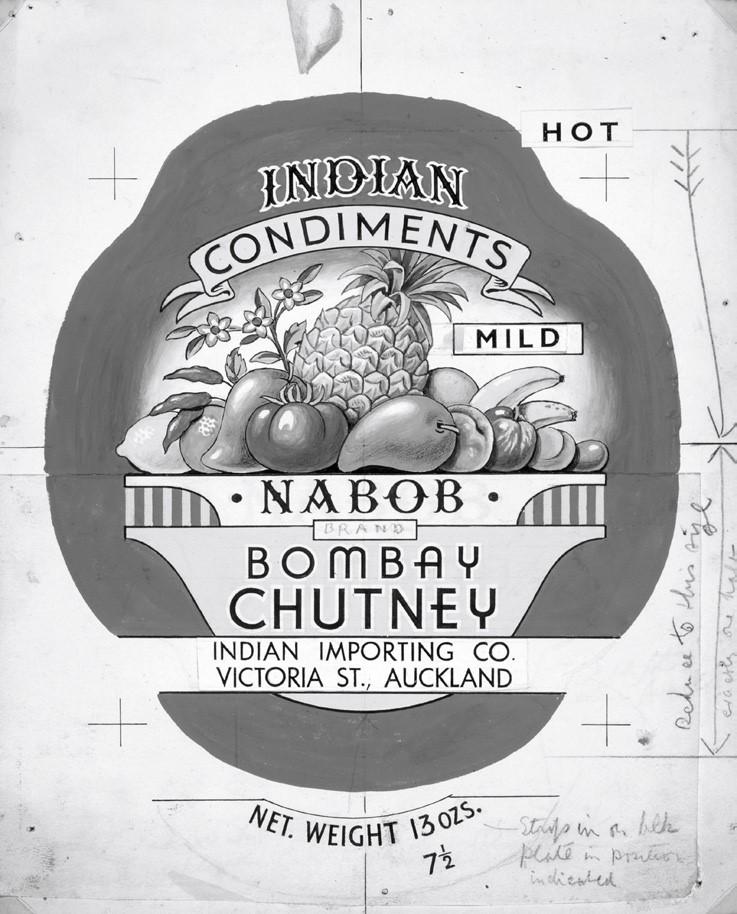

As some believers continued to eat meat, the size of the vegetarian Adventist community is uncertain. The significance of Adventism lies rather with the doctors and missionaries who endorsed vegetarianism as a safe, respectable, and Christian way of eating, and the Adventist businesses that created a kind of infrastructure for vegetarians. The Sanitarium Health Food Company factories produced wholegrain cereals, coffee substitutes, tinned fake meats, and peanut butter.[187] These offered convenient, easily prepared sources of protein in a time when tofu was familiar to only a few Chinese immigrants, vegetable oil was hard to obtain, and the range of vegetables was limited. Sanitarium published vegetarian cookbooks with nutritional information, and Adventist cafés opened in Auckland (1901), Wellington (1906), and Christchurch (1907), enabling vegetarians to eat out more easily. Often Sanitarium restaurants also acted as health food outlets, selling wholemeal bread, Marmite, dried fruit and nuts.[188] There was even a vegetarian nursing home in Christchurch in the early twentieth century.[189]

Arthur Daniells and food reform in Napier

Long before the first Sanitarium health food cafés opened, Edward Hare’s brother Robert and the American missionary Arthur Daniells travelled to the Hawke’s Bay to spread the Adventist faith. Their mission included vegetarian propagandising.[190] In 1888 Daniells pitched a vast tent in the south-west end of Napier’s new Clive Square, next to the Temperance Hotel, creating a canvas church that could seat three hundred people. Here he installed a new American pedal organ, and Miss Gribble, a musical local resident, prepared to lead the singing with her ‘fine and cultivated contralto voice.’ [191]