Jerry Rubin

Positively the last underground interview with Abbie Hoffman... (maybe)

Stoned is the best way to appreciate Abbie Hoffman.

Once one of the most visible and persistent symbols of the ’60s, the mythmaking co-founder of the Yippies (along with Jerry Rubin] has been a fugitive for the last six years, ever since his 1973 arrest in New York for conspiracy to sell cocaine.

Since then, the 43-year-old madcap political prankster has lived underground as another person, changing his features with plastic surgery and shedding identities as frequently as a snake does its skin. Unable as Abbie Hoffman to continue his marriage to his wife, Anita, he left her and his then two-year-old son, america, in February 1974, went underground and married someone else (Abbie doesn’t believe in divorce). But vacating a persona is not so easy. At least twice during his travels Abbie has freaked out, including one time in Las Vegas where he ran through a casino yelling out his real name. Remarkably, he was never caught. But the overlapping personalities have left their mark. His sentences don’t always proceed in logical order, the words are hieroglyphs of a bigger picture, precision alternates with metaphor, and there is uncertainty as to whom the personal pronoun I refers to. A puzzle for even the most astute psychology student.

Abbie, the son of a “legitimate” drug salesman from Worcester, Massachusetts, started out by studying humanistic psychology with Abraham Maslow at Brandeis University. But he was “born” in 1960, he says, when his massive and naive faith in the American myth (“truth, justice and the American way”) was shaken by the intruding reality of war, racism and generational revolt that characterized the ’60s. After working in the civil-rights movement in the South in the early part of the decade, Abbie returned to New York and opened up Liberty House to sell poor people’s products from Mississippi, then abruptly changed his lifestyle by becoming a digger (a political prehippie) on New York’s Lower East Side. This was the start of a new American myth, and a new role for Abbie as a new American mythmaker.

Aided by television and its quick dissemination of image, the United States during the ’60s underwent a violent metamorphosis of styles and values more rapidly than was ever possibie before. It was Abbie Hoffman’s genius to learn how to use the media, how to manipulate it to carry messages against the Vietnam War, for marijuana, for community consciousness. “The Sixties,” as writer Marvin Garson once said, “were staged.” Life and politics were transformed into theater for the television cameras. And Abbie Hoffman was one of its prime directors.

Hoffman wrote messianically of new lifestyles and values in his books Revolution for the Hell of It, Woodstock Nation and Steal This Book, the latter a kind of kamikaze attack on corporate consumer society inspired by a digger pamphlet he authored earlier in his career called Fuck the System, by Free. But the culmination of these works, an autobiographical recapitulation of Abbie’s life in the ’60s, will be published in April by Fred Jordan Books, distributed by Grosset and Dunlap. Called Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture(the movie rights have been bought by Universal), it recounts the incredible rites of passage of the individual and the nation during that tumultuous decade.

Ordinarily, the issuance of a new book is not enough to make High Times jump to do an interview. In fact, another interview was originally scheduled for this issue— until we received a phone call from the protean mythmaker himself. The message was clear: He was planning to come up soon, and this might be his last interview on the run.

For such a special occasion, we chose Jerry Rubin, Abbie’s former partner in crime, to see if he could get Abbie, on a friend-to-friend basis, to open up as never before. Jerry as much as Abbie was responsible for the media absurdist politics of the Yippies, and his best-selling book Do It! was perhaps the most widely read example of the guerrilla theater of the time. In fact, so intertwined were the activities of the dynamic duo that to the majority of the American public they often seemed to merge into a single entity known as Abbie and Jerry. The two of them have maintained a close friendship during Abbie s underground sojourn. Naturally we were curious about what kind of chemistry might transpire between them after long estrangement from public collaboration.

Another unknown was Abbie’s feelings about a third figure of the ’60s, Tom Hayden, who along with Jerry, Abbie and four others became enshrined as a member of the Chicago 7. The 1969 trial was an attempt by the government to derail the counterculture by incarcerating its leaders on trumped-up conspiracy charges growing out of the demonstrations during the 1968 Democratic convention. It will go down in history as an example of the way political fights can be waged in the courts. Since that time, Hayden, whose Port Huron Statement led to the founding of SDS in 1962, has left radical politics, married movie actress Jane Fonda, and waged a nearly successful campaign for the Democratic senatorial nomination in his adopted state of California.

Getting Jerry reservations to go underground was not easy, but we did manage to send him there. While doing a college lecture he met Abbie at a hotel in Mississippi. This is what he reports: “Abbie is a tough interviewee. He likes to tell stories instead of giving direct answers. Later, when I confronted Abbie with this, he replied, ‘Telling stories is an old Jewish form of defense.’ I had wanted to slip past the defense, get at the man behind the myth.”

Rubin: You’ve been a fugitive for six years now, ever since the State of New York charged you with conspiracy to sell cocaine. What are you facing?

Hoffman: Fifteen or 25 to life imprisonment, probably in some cage in Attica.

Rubin: Would you get extra time since you’ve escaped them so long?

Hoffman: Well, you get five for jumping bail; interstate flight—that’s extra. If I get caught it’s very, very bad, very hazardous. I could get killed. It’s the fame factor. If you’ve been seen on television it’s magnified into super power and magic by viewers, and the police translate this into violence. They see you as ten feet tall. If they burst in here right now I’d have to immediately be calm and reassure them: “I know you’re doing your job, guys. I’m doing mine. Don’t worry, nothing is going to happen, just get out the handcuffs.” I’ve played this scene so often in the past, you know. The danger is they misunderstand exactly who you are and can misuse their guns. I want to live as long as Abraham. I have a lot to do in life and don’t want to go down at the hands of a shaky policeman or run down by drunken reality.

Rubin: But you occasionally seem so reckless to others. Not to me; I think you’re basically deliberate.

Hoffman: Well, I enjoy the sensation of being swept along by my own reckless abandonment. That’s my motto for the ’80s. By definition of living an outlaw’s life I must live every moment on the edge and to its fullest. But the planning is behind the scenes, in my mind’s internal dialogue—where I’m constantly testing and rejecting—and in the years of discipline and determination required to be here now in this very spot, being hunted while all around me is chaos and faulty communication.

Rubin: I see you as an outlaw. Is that your childlike romance coming out?

Hoffman: Fugitive is the government’s word. Its derivative is Norman. Outlaw is Anglo-Saxon. Robin Hood was an outlaw. The people called him that, not the sheriff of Nottingham. This is extremely important. We in America, probably more so than any other place in time on earth, have such a problem being precise about our language. But language shapes our environment just as much as the opposite. You become what the media label you. It takes great power for anyone to resist media. It is the burning micro frying the brain. I see that all much more clearly now that I’ve lived in rural settings for so long. But to answer your question on childish romanticism, Herbert Marcuse, who was one of my great teachers, once told me we have all our creative thoughts by the time we’re 18. Therefore, if we’re interested in creating a new planet, it’s kind of stupid to scorn childishness. My kid america is already a wise old man, but you have to find and meet him on his terms. The same with animals and plants. City people don’t have the patience for that.

Rubin: I still don’t understand why you are not caught. You’re so public. You appear in magazines, you contact people.

Hoffman: To use a Yippie four-letter dirty word, it took a lot of work. It took a lot of work, it took a lot of discipline and maybe some luck. A lot of brains. I’ve learned to survive in a number of different kinds of jungles. I was lucky in that sense and in that I have the kind of friends that money can’t buy, which unfortunately doesn’t hold true for most of the other 300,000 fugitives, who are always on my mind.

Rubin: Maybe I’m going out of my role as an interviewer, but I think that you have an ability to get people to really love you. And that’s the source of this support. Also you are a source of power to people. By being powerful yourself you’re able to liberate people to their own potential. I think that’s why you do have so many people who support you.

Hoffman: This is hard for me to take. I think I’m much more human than when you knew me back then. I’m humble because I cracked up on the run. The wife and I had to lick the gum off food stamps to survive and I had to separate from my kids and everybody I love. I had to deal with immense sadness, which I’m not exactly sure I ever had to deal with before. I had no choice but to do it or perish; to learn to love and survive or die. You probably experienced this when your parents died in your early 20s.

Rubin: But I was too young to mourn.

Hoffman: Too young to mourn? I don’t know about that. I see some of those boat people’s kids. “Boat kids.’’ They look like they’re mourning right off. Grief is grief. Loss is loss. Probably it’s more drastic for the young, and that’s why you’ve repressed the feeling.

Rubin: In the mid ’70s you really made a personality transformation, living as a nonperson. You had to learn to live without the crutch of “Abbie Hoffman” actually. You have become a whole new person.

Hoffman: That’s right. I’m at a party in Paris, this fashionable party, and I’m nobody. That’s me. I’m a nobody. No fame, no money, no background. Part of the wallpaper. Right. And I’m trying to engage this pretty young woman in conversation. I usually avoid the ’60s and things like this. But now I’ve got to have views. It’s a verbal party. And the talk goes to this: “So, you’re from America?” The U.S. and the ’60s and what did you think of that? And I give a view of what I think of that. And this is a nobody talking to a woman. She says, “What do you think of the Chicago conspiracy trial?” And we talk a little bit about that and she says, “What do you think of Abbie Hoffman?” And I’m about ready to give a view and she says, “Excuse me, there’s somebody I recognize,” and she walks right out of the conversation because I’m a nobody. I’m not rich. I’m not famous. Incredible.

And what delighted me, what made me I feel so good inside, was that I didn’t take | that too personally. I didn’t feel threatened. I I didn’t have to announce myself. I didn’t feel that my ego was being threatened. I just sat there and I said, “Holy shit. Ain’t people fucking interesting.” I’d have to be the blindest schmuck ever to graduate Brandeis not to recognize that as “growth.”

Rubin: I know people are more interested in me when they find out my name.

Hoffman: Yes. My past identity gave me access. My ceasing to be a nobody had to do with my community organizing during the last two years, when I became another person and assumed my underground identity. I was learning all these skills and living in a rural environment and I didn’t even really have a last name. It’s a small town. I was learning country things: carpentry, horse riding, about weather and wildlife, about listening to others, how to say excuse me and thank you. But something was missing: my reason for existence. Then along come the bureaucrats who want to destroy the valley and put in a nuclear power plant. Someone says to me, “Your little peaceful scene that you built here, your home, is going to be destroyed.” So I go and I study the plans of the engineers and bureaucrats and I say they’re right. And I’m the only one in the valley that can beat them. I’ve won this battle a hundred times. I have no choice but to fight on every level. It’s my home. I built it with these hands.

I care about democracy and the valley people isolated from power. What I learned in the ’60s was how to penetrate the power structure from the street as a nobody. I call that a revolutionary. When lots of people do it it’s a revolution. The ’60s were not the second American revolution, but a civil war, brother against father, family against neighbor. In our valley everyone supports our committee. We are not to be confused with the antinuke marches. We are out to change America, and we, the ’80s, are the true second American revolution. Believe you me, when you see Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture by the biggest movie company in Hollywood, you are going to see the people of every small town in America, my neighbors and my friends.

The people that are involved are farmers and hunters and small business owners and people like that, as well as your pot-smoking backpackers. In order not to get caught I had to be very cautious, very deliberate. I changed my accent. I had to learn the way everybody talks, their manners, the relationships of all these people. We won the battle, by the way, and have gone on to try to capture political control of our country, our state and our nation.

Rubin: How did Three Mile Island affect you?

Hoffman: Well, what happened was it became fashionable to join the antinuke movement. Everyone got involved too quickly because a crisis had occurred and so people started noticing our work more. So Abbie had to withdraw from media land and rethink his whole thing. How many chances could I now take? How much should Abbie talk about the nukes? I’ve decided to broaden the discussion to the environment as a whole, to realize the war in Vietnam—all imperialism—is a war of ecology.

Rubin: But you didn’t retreat. I saw you at the MUSE office one day.

Hoffman: I also wanted to help MUSE. I mean, the idea of musicians being involved in a cultural/political movement on that level—Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Bonnie Raitt, John Hall and those terrific souls—is great. As are the feelings I have about David Fenton, Sam Lovejoy, Obie Benz, Harvey Wasserman, Holly Near. Hey, I wrote the goddamn book Woodstock Nation. This was a ten-year dream. I was at two of the concerts and the rally. For me this was a dream come true.

Rubin: Don’t you have any doubts?

Hoffman: Yes, of course. I want to hear the Russians’ point of view. I have great mistrust of Tom Hayden, “the candidate.” I mistrust young whippersnappers, wet behind the ears, who don’t listen to people like Dave Dellinger, Dan Ellsberg, and who want to put one worker on the board of the big corporations. That’s Uncle Tomism. I mistrust an audience that would go to see Bruce Springsteen (who I loved and who was the hero of the event) but wouldn’t care if it was anti nukes or pro Nazis or pro banana babies. I question a movement dominated by spoiled rich kids who play at revolution and did not have to try and change America when it literally meant shedding your blood and going to prison for your beliefs—not being given Madison Square Garden and getting your cock sucked by the media moguls—back in the early ’60s.

This, the ’80s, is the real thing, and these young kids better be for real or America and the planet are lost. I agree with Ralph Nader: We don’t need ten-year phaseout programs and compromises with the aerospace industry of California. We need to tear down the plants now! Nader is more honest than Tom and Jane at this point in time. He’s making progress; he’s the one I want to meet, not the Flying Fondas.

Rubin: Getting back to your alleged crime.

Hoffman: My what?

Rubin: Your coke bust.

Hoffman: I’m innocent. Completely innocent. Crime is one of the most complicated words to define. One person’s crime is another person’s means of survival. The prosecutor asked for $500,000 bail in my case as he adjusted his tie for the newspaper boys. He said, and I quote, “This is a crime more heinous than murder.’’ That was six years ago. Now the prosecutor, that same guy, is a partner in a dope case with one of my lawyers; he goes into court and claims coke is harmless. He gets clients off. He’s a good lawyer. So who’s on first?

Rubin: Are you willing to go on trial?

Hoffman: Yes, I am. I’m willing to take a lie-detector test. The problem is the structure of the court system. You and I spent a lifetime in courts. We know it’s got not very much to do with truth. Remember the time in our Chicago trial when the prosecutor read a few lines from my “handbook of revolution” [Revolution for the Hell of It]? Well, our attorney offered to let each juror have the entire book to read. No go. Remember how the former attorney general, Ramsey Clark, was kept off the witness stand? Remember the jury with a median age 20 years older than ours, remember the collusion, now on the public record, between the judge and the FBI? Before I went on trial the courts would have to convince me they, like I, are no longer living in the past. I’m in search of truth. The question I raise is, is our system of law in search of truth?

Rubin: How do you feel about coke?

Hoffman: Cocaine? Well, it’s certainly not a narcotic as defined by every test other than legal. It’s a beneficial stimulant if used correctly. Just ask the Peruvian Indians and all the executives. I’ve met coke dealers whose clients include many of our finest New York judges. The New York Post isn’t quick to call those people “junkies” and demand the streets be swept clean. Cocaine, like any stimulant, has to be properly used, of course, or it can be dangerous. It can screw up the lining in the nose, and if overdone….Malcolm X had the best definition I’ve heard yet. He said it made you feel like Superman of the moment. I should include, as I say in the book, that making coke illegal was a political decision made by racist bigots many of whom were themselves either alcoholics or morphine addicts. I don’t do it much because I can’t afford it. Last night I saw the original version of Modern Times. Did you know there’s a coke scene in that movie? In other versions I had seen it had been censored. I hate censorship. Like Cole Porter’s publishers being forced to change “I get no kicks from cocaine” to “champagne.” There are coke dealers that say I’ve done more for coke than anyone since Freud. There are smart lawyers that say I’m the one with courage enough to fight this through the courts to make coke legal.

Rubin: So why not surface?

Hoffman: Well, I really don’t want to go down in history for that battle. I just don’t want to misuse my energy working as a guinea pig for the court system. I know all battles are important, but right now I’m concerned about saving this beautiful land called America. They would have to make me an offer I really couldn’t refuse.

Rubin: But what if you get caught?

Hoffman: Oh, a disaster. Aside from the accidental shooting I mentioned above, I’d ruin a good movie ending. No one likes to “get caught.” How did you feel when your mother opened the bathroom door while you were masturbating? God, I’d probably pass out, my whole world would be shattered. Many of Abbie’s friends find it difficult to believe, but I am only “acting” the role of Abbie. I am someone else. Let’s call it my B identity.

Rubin: I think that’s what is so fascinating about your six-year odyssey. The ’70s were a time of changing identity—your ending of the book indicates that—and I want to compliment you on such a creative writing achievement. The ending implied you have metamorphosed into another person. You really did the ’70s trip of self-awareness.

Hoffman: Yes, that’s right. There were a series of changes and great confusion and agony, the crack-ups on the run I describe. I hope to do literary justice to the intensity of the experience. But R.D. Laing teaches that “breakdown” can also be “breakthrough.” Each crack-up taught me important lessons about pacing one’s energy, about humility, about being a better person. But I am a different person. Really different. I have an identity I refuse to give up no matter what happens, because I love who I am. It’s not a metamorphosis in any Kafkaesque sense because Abbie was and is my hero, just as he is and will be for millions of others.

Rubin: Aren’t you getting a little bigheaded here?

Hoffman: Well, I know the movie story. I understand movies, I learned about our country by watching movies. That’s the significance of Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture. I’m an American hero. Hey, it’s better than most jobs around. I’m lucky and I don’t want to die, that’s why I, me, this body, could never come back as Abbie. I just don’t want to live last year’s movie any more than Jean Stapleton wants to go on living as Edith Bunker, Archie’s wife. I mean, would you want to go around being confused with a frizzy-headed doll wearing a flag shirt when you’re 80 years old?

The first thing I would do if I had to surface would be to legally change my name. That would be the quickest way to make a long story short. If they just quietly dropped the hunt and the charges. I’d make no fanfare, just keep right on doing what I’m doing.

Rubin: I’ve seen some of your other life. How much can you talk about?

Hoffman: Well, much of that will be in the next book, and the movie. I’m an environment activist, have been for over two years. I live in a beautiful valley. I dedicate the book, of course, to my wife and the valley people who taught me truth, justice and the American way. I’ve been on radio, TV, spoken in barrooms, passed out leaflets, done office shit work, raised money. I work as hard as I did on the Chicago trials.

Rubin: I find it impossible you’re not discovered.

Hoffman: Maybe I have been. My neighbors are very shrewd people. My model is the Clint Eastwood movie, The Outlaw Josie Wales. He’s a fugitive renegade from the Civil War who’s chased by a posse but eventually arrives and settles in a valley. His neighbors protect him when the posse shows up. There’s no gun battle. They just point a different way: “He went thataway.” For all I know that’s happened already. There was a rumor, but right now I’m a valuable member, well respected and loved by many in my community. And the love is mutual. Angel, my wife, led me through the valley of the shadow of death up the mountain of hope and down into the heartland valley of life. She’s my last wife, my running mate. We’re very close and very in love.

Rubin: And Anita—I was moved to tears by the great love you show for Anita in the book and what a great pain separation from her and america, your newborn son, must have been. For a year I shared your grief.

Hoffman: Thank you. That’s why no matter what happens to us down the road, we’ll always be close friends. And as to Anita, she and I are lovers, but, well, like, I talk about all the fucking in the movement in the ’60s. Let’s just say now, I don’t mix that sort of pleasure with business.

Rubin: Speaking of business, are you insulted if I call you a good businessman?

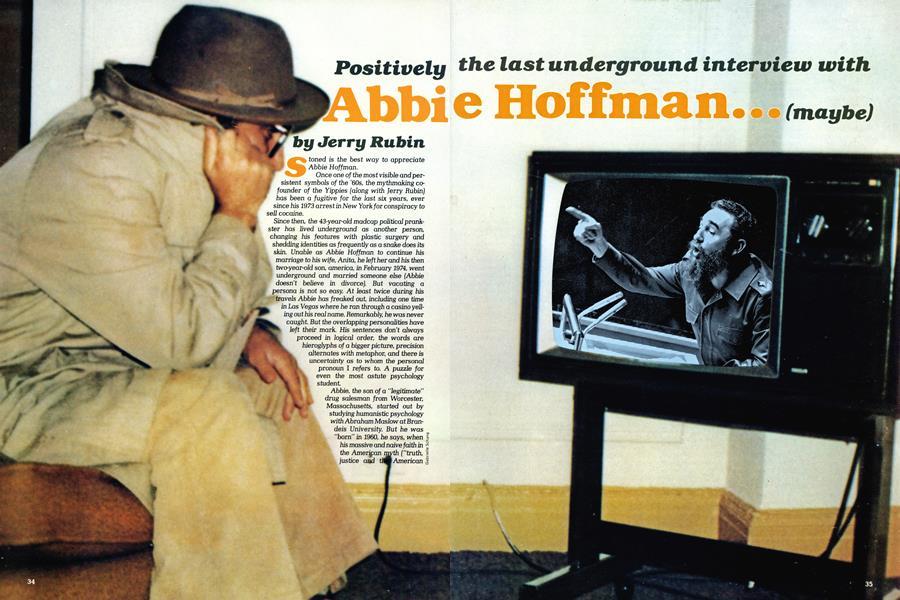

Hoffman: Not anymore. Fidel Castro and my father, Johnnie Hoffman, taught me that not only is there no contradiction between being a good businessman, a good man, and a good revolutionary, one must be all three, unless, of course, one is a woman.

Rubin: Abbie, let me tell you that when I go on the college trail these days I’m asked a lot of questions from a tiny minority. And there is the question that the reporters have: “Are you a relic of the ’60s?” How would you answer that question?

Hoffman: I’m not sure I’d waste my time. Actually, I don’t feel compelled to say I’m not a relic. Relics are very valuable anyway. I don’t feel a need to explain myself. It’s just a dumb question because why would a reporter be interviewing a has-been anyway?

I just want to show people what I can do because what I can do, they can do. I did it twice, and I’m just an average kid.

Rubin: How interested do you think people are in the ’60s these days?

Hoffman: The ’60s are an emotional attitude, which I’m sure is what we both understand it to be. An emotional stance. They are absolutely fascinating. Nostalgia for the decade is just starting. You can see it in Hollywood. This fall they are going to present a three- or four-hour reenactment of the Chicago conspiracy trial. Jeremy Kagin is the director, a perfect choice. There’s the movie they’re going to make from my book, there are several other ’60s-type books, and I think that all of this is becoming of great interest to people because they’re going to want to know about it. It’s time. My kids want to know. My wife is curious what SDS means and she is my contemporary.

There were many ’60s for many people. I learned that living underground, because you walk down the same streets on the Lower East Side or in Mississippi, or Berkeley or Chicago, and it’s a you, the B personality, that did not experience the ’60s as the A personality did. Everyone is such an egomaniac under capitalism. Think how we use the expression “Everybody’s doing it” when we mean our circle of friends or Walter Cronkite’s circle of friends. All that’s going to change in the “We” decade.

Rubin: In the early ’70s you couldn’t get someone interested in the ’60s for anything.

Hoffman: Well, the ’60s for me never died on one level. And I said that on the tenth anniversary of the Chicago conspiracy trial case. Because we fought against an imperialist war and we won. We have to make this absolutely clear. That’s what Apocalypse Now and all of those revisionist movies fail to make clear. The empire collapsed, and good riddance to bad rubbish. There were two sides. There were the villains and there were heroes, as we saw it. And we, the antiwar forces in America and the Vietnamese, were some of the heroes and those bastards in the White House and the Pentagon were the villains and we won. The proof is that American troops are not fighting in Nicaragua, in Latin America, in Africa, in Iran. Until the troops go out again in force that way, I’ll say the ’60s still live. That’s why my book is a true story: It’s history. If some of the heroes don’t write the history, the villains will. McNamara will get a peace prize. The villains’ view of history will be the ’50s going on ’70s. It won’t be ’60s going on ’80s. Do you see what I mean? To the villains the ’60s will be only a momentary interruption in the building of the American Empire. We have a revolutionary duty to never let that happen, to follow through.

Rubin: You want to be a major interpreter of the ’60s?

Hoffman: My book is to set the record straight. I wanted to start with what happened to me in 1960 and before. Not the ’60s: 1968 to 1972. I wanted to show the transition of the building of a revolutionary and how my own consciousness was developing and how these events were happening to me. Here we were coming out of the ’40s and ’50s, you and I, with our great love for America. Great belief in all the myths. Total gullibility. Not even knowing the Rosenbergs had been executed. And then you see and experience what happens and you’re just shocked constantly. It happened with HUAC [the House Un-American Activities Committee] and the execution of Caryl Chessman and it just kept going and you just didn’t believe it. I didn’t believe Kennedy was assassinated; I didn’t believe we were put on trial in Chicago. I didn’t believe we were being dragged before HUAC. I didn’t believe we were being beaten up and not given a chance to protest. I didn’t believe any of this stuff, because I believed in the American dream of democracy, and all that time those sons of bitches Nixon, J. Edgar Hoover, John Wayne, LBJ, they were spitting on the flag, not us. And now I can read government documents released under the Freedom of Information Act and now I believe it. We got Watergated before it was fashionable. You know what I mean. We didn’t have Woodward and Bernstein and these other investigative journalists around. We were called paranoids by the press.

Rubin: But people said it’s okay to Watergate us because we were calling for a revolution.

Hoffman: Calling for a revolution? Well, I grew up in Boston where revolution was not a dirty word. I wrote a long paper in college about the battles of Lexington and Concord. I can do an hour stand-up comedy routine about the battles. I know the whole history of the minutemen. I compared my youth to Samuel Adams’s several times. I know they ran the first underground newspaper, the Massachusetts Spy. I know all that kind of history, and then to leave Boston and hear the word revolution was bad was weird for me. So that’s why in the end of my book, when I write that when all today’s “isms” are tomorrow’s ancient history, there will still be reactionaries, there will still be revolutionaries. When ABC-TV during the ’60s interviewed me on the Concord Bridge, the DAR and the Legion forced the Lexington City Council to try and sue ABC for illegal trespassing. As things now stand there’s a town ordinance that you need a permit to film on the Concord Bridge. Ridiculous, because at this moment hundreds of people are doing it without a permit and no one seems to be screaming. Go tell me about the law!

Which side are you on? Because I think the word revolution implies growth. It implies change. It isn’t as determined as evolution. It doesn’t imply that Darwinian determinism. So I’m quite happy to say I’m a revolutionary, much better than to say you’re born again. Well, I’m born…

Rubin: Now everybody knows you’re very angry these days about Tom Hayden.

Hoffman: Disappointed.

Rubin: Why are you disappointed?

Hoffman: That’s all in the book. But let’s say it’s political differences: Because I see what he’s doing as subversive and dangerous to the movement. He has a conflict of interest. He is “the candidate” and he is the “spokesman” for the antinuke movement right now. Now that’s a movement that’s growing and has to develop its own philosophy from the bottom up, and over here is “the candidate” wanting desperately to be elected at any price. Those two things come into conflict just as much as does being chairman of the board of General Motors and trying to be senator. You’ve got to resign one thing, you can’t have the other. It’s a conflict of interest. When he talks about strategy it has to be in line with the needs of the aerospace industry in California. He has to separate the issue of nuclear weapons from nuclear energy plants. Because that connection is unrealistic to his right-wing component. He has to embrace Proposition 13. And try to align that with a whole welfare program that has to go on revitalizing the inner cities. That’s something that can’t be done without lying. What he’s doing is sending out pollsters. He and Jane send out publicists, press agents, to spoon-feed the people. I’m not going to say feed the people what they want. They’re going to feed the people what the people think or are told they want in order to get elected. And that’s a long way removed from philosophy and statesmanship; it’s a long way removed from truth. I fail to see any “new” politics here.

These are complex problems that have to be worked out by the people. Tom Hayden is not now and never was “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” He was and is an elitist. He likes shuttle diplomacy, dealing with the top level of society in terms of changing things. He doesn’t come from the bottom up and I don’t think he gives a fuck about the sun. I could say a lot of good things about Tom if you feel it’s necessary. He was a good organizer in Newark; the Port Huron Statement—but Tom turns too many people into objects to get what he wants. He betrays friendship. He places political ambition over personal friendship. Which I don’t consider a new form of politics. And I’m not the only one. I’m not alone when I speak to you about Hayden. When I’m talking about Hayden I’m breaking a ten-year silence where I wasn’t going to say anything bad about any of the people in Chicago.

Rubin: What’s the story? What happened?

Hoffman: He told my wife Anita that I’m a common criminal. What does that mean? Of 450,000 people who were busted for dope, what does that mean? That they’re all going to stay in jail. I knew he never liked the counterculture. I’m common. What does common mean? Common? What a jerk!

Rubin: Well, when did he call you a common criminal?

Hoffman: To Anita. She went to him for a job and he told her nobody in this town will hire you when your husband is a common criminal.

Rubin: On the telephone or in person or what?

Hoffman: Face to face he said it to her. She went to see him. He’s insulated. It’s hard for the wife of an old friend, a former cellmate, it’s hard for a woman now working as a waitress in a Pizza Hut to reach “the candidate.” If you asked him about this rejection, about why he didn’t—of all the people in the Chicago trial—show up for the Bring Abbie Home Rally, he’d lie, say he forgot or no comment. That’s how he handled the Jane Fonda-Joan Baez big debate on Vietnam, the boat people thing which was never really handled. He never signed the letter criticizing Vietnam. He said he lost the letter and wasn’t dodging the issue. Liar. Politician. “The candidate.” Fuck him. He’ll be president, I’ll be in the mountains fighting him. And then we’ll have a real revolution going on. Just like in Latin America. Che Guevara’s fighting his classmates. I’m not running for president. I’m just running…

Rubin: So you wouldn’t support Hayden for senator?

Hoffman: No. I wanted Shirley MacLaine last time and Tom blew it. Tom thought it was a good idea so the next morning he decided to run, and now he’s his own candidate. I’m following his tour very carefully—every single speech. The latest good idea between Jane and Tom is that the first rule is to maintain a sense of humor.

Rubin: Where did they say this?

Hoffman: In Washington. In each stop they take back something from the past. It’s incredible to watch the tour. They keep taking things back from the past.

Rubin: What do you mean?

Hoffman: They’ll take back the Vietnamese when their kid’s name changes from Troi to Troy. But here they are, back on the road again. Hayden and Fonda. The Honda. Honda baby. And what are we taking back? Jane is now taking back everything in Washington. Take a look at this article I’ve been saving, written by some ass-kissing groupie from the Washington Post. She’s asked about Jane once saying that Huey Newton, the Black Panther leader, “is the only man that I’ve ever met that I could trust as a leader in this country.” There are a few kidders in the back room waiting to see how she’ll handle that one. The famous double take, the eyes roll. Take it back. “All I have to say about that is that I was naive and utterly wrong.” Fonda sits down to a burst of applause. And each stop is like that. “Did you say?” “No. I’ll take that back.”

I want to go on record as saying that Huey Newton was a hero of the ’60s and that in all my dealings with him he was a gentleman and a scholar. Of course I didn’t go see him as a Hollywood starlet on the make. I went to see him about getting Tim Leary, an escaped convict, into Algeria…. But I’m giving away too much of the book.

Tom really lied to me once. I didn’t even tell this story in the book.

Rubin: Can you tell High Times?

Hoffman: Oh, the big climax in the trial when we’ve got to go for the judge’s robes and all that. And we’ve got to disrupt him. We’re not martyrs and we don’t want to go to jail. Right. You remember that moment when Tom says Dave [Dellinger] should. You know, he’s a pacifist and pacifists want to go to jail. Tom’s always had that ability, which is very useful in politics, to make objects out of people. I pulled him aside in the ACLU in the toilet room after Dave was arrested, and Tom had indicated that we do nothing in the courtroom because he had some plans afoot. And I said, “Tom, what are you going to do? You say you have this little group of people. Aren’t you promising something?” And Tom said, “We’re going to firebomb the Chicago Tribune at the end of the trial.” So I said, “Can’t you do it tonight?” And he says, “Yes.” Well, nothing happened. You and I put on the world, he put on us. He put on me. He put on his friends. Well, we just put on the world. If we said 500 million people were coming to Chicago, that’s considered a lie.

Rubin: At that moment in that bathroom was Tom Hayden planning that act? Was he maintaining a revolutionary pose to hook you in? Was it a total pose?

Hoffman: Well, total pose. But I’m not out to do him harm. This has not got to do with Tom, by the way. This is all constructive criticism. This is not revenge. This is not a war. I don’t want to destroy Hayden. This has to do with constructive criticism, which is what I believe in, and truth.

I’m out to torpedo the image that he’s projecting: “the candidate.” I’m out to do “the candidate” in and try and help him become a statesman.

Rubin: So you’re saying that Hayden was playing a role in the ’60s as a revolutionary, and now he’s playing the role of the candidate. And manipulating people. Why do you think Jane Fonda’s giving Tom such cover, and what do you think of Jane?

Hoffman: I separate the two of them as individuals although they are moving together as, I guess…

Rubin: They’re a collective…

Hoffman: You can still separate the two people. You must. You have to treat individuals as individuals on this level when we’re talking, and I’m going to talk about the difference between them because it has to do with where you’re coming from and where you’re going with images. Jane Fonda. Hollywood. Barbarella. Movie actress. Moving toward brain. Thinking. Getting more sophisticated. And all that. That’s a positive move. We have Tom Hayden. Coalition activist organizer in the streets. Revolutionary. On trial. Destroy the system by any means necessary, moving toward a corporate position where he’s willing to settle for one worker on the board of General Electric, put on a suit and tie, not legalize marijuana, and next you’ll see him praying in church a lot. He’ll not talk about the rights of the Palestinians for a long, long time because he’s heard the Hollywood street gossip that he’s anti-Semitic.

You know, some people say that I didn’t do Jerry Rubin justice.

Rubin: Me?

Hoffman: Yes. In the book: Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture.

Rubin: Who said that?

Hoffman: The book’s editor.

Rubin: I thought it was okay. It wasn’t a book about our relationship. It was a book about your adventures through the ’60s, and I thought the things you said about me were with few exceptions pretty appropriate. Perhaps there were some unnecessary things.

Hoffman: Unnecessary. Uh-huh. Unnecessary. I was trying to get me and Rennie [Davis] together there. Wait. Unnecessary. Yes. There are some unnecessary things, but I heard you said to the editor, “Did he talk about how we fought?” And he said, “No, there’s no fighting in there.” You wanted me to be a little more…

Rubin: No, no, no, no. I say in my speeches that there was ego competition between us. It’s just human. I mean, it’s no judgment or anything. And maybe my insecurity was the source of my competition. If I had been a more secure person, there would have been no need for me to compete with anybody. Right?

Hoffman: I wasn’t competing. I wasn’t competing with you.

Rubin: Well, you’re very competitive. You’re incredibly competitive.

Hoffman: Maybe with Muhammad Ali. He said he was the greatest and I knew I was. Maybe we’ll have to reduce this to sports.

Rubin: All right.

Hoffman: We have to see. We’re in a game and we’re competitive and you’re the quarterback on this side and I’m the quarterback on this side and now the game is over and we’ll go out and have a beer together and make jokes about all the spectators. That’s the kind of competition that I can understand.

Rubin: Yeah, but the level…

Hoffman: I never practice the kind of competition that demands that I have to reduce you as a human in order for me to grow. I totally reject that sick shit. I’m not General Patton! Let’s talk about a difference that I didn’t put in the book that really fascinated me. What are different kinds of courage? Now, Jerry, you described yourself as a coward.

Rubin: Did I?

Hoffman: In Growing (Up) at 37? Yes. You’re Jerry Rubin, this public guerrilla to be feared, and inside is a little boy who’s afraid and…. Right?

Rubin: Oh, yeah. Right.

Hoffman: Right. You are describing this difference between the internal and the external. I studied psychology for all that kind of stuff with Abe Maslow. I played football and other rough sports. So in a certain sense, when things were sort of rough in the streets we rioted in together, I was sort of used to it. I didn’t think you were, and you kept doing it over and over and I kept saying in my head, “Why is he doing this? This is so hard. He’s working so hard to overcome this fear. This is incredibly courageous.”

Rubin: Yeah, I see that now.

Hoffman: It’s like what I wrote in the front of my book: just what you’re supposed to do with fugitives. You’re not supposed to point. We recognize you before you recognize us. We’ve got very good vision and the way you say hello is just smile and nod. You understood a little better than I actually. You taught me that because Bill Ayres and Bernadine Dohrn told me to thank you for not approaching them one day.

Rubin: Oh, I remember that, yes, yes…

Hoffman: You know, someone said that once you reach 30 the friends you make are the friends for the rest of your life. What do you think about that?

Rubin: You mean the friends you have at 30?

Hoffman: The friends that you make, say, in your early 30s. The first 15 years are incubation. The next 15 years are for study. Basically, power is fought between the people who are 30 to 60. And this is the whole dynamic of history. And once you’re over 60, the grandparents, you can align with the people who are really younger. But the basic penchant of history is fought between 30 and 60. And we saw that back in the ’60s and the non-Yippies didn’t. Have you ever studied demographics or looked at demographics as the reason for the ’60s?

Rubin: Sure.

Hoffman: The baby boom and all that. We were the masses. We’re still the most, and by now we’re over 30.

Rubin: And so we’re not pushing…

Hoffman: But we still are “the” culture. We still do determine it. If you look at the magazines, if you look at the fashions. If you look at what you call the ’70s. What are the issues? How do couples relate, and myths, and childbearing, and men to women. Who’s on top and who’s on the bottom. You think 17-year-olds give a shit? Or grandparents? We were, as you remember, glorious about being action freaks. It was the apocalypse. It was war. We acted on impulse. We had to. There were some people quick on their feet. Some not so quick. We were certainly quicker than the generals in the Pentagon. If you read our books during that period they are cheering everybody on. Let’s go team! Rah, rah! You know, it’s not like “this is why we do things” and “this is how we didn’t” and “this is because we were doing it!” We were doing it at the moment. Dwight Macdonald, my crotchety old friend, once said to me, “Whatever possessed you people in the ’60s? The idea of acting on your ideas is so against the intellectual tradition. It just doesn’t make any sense.”

Yeah, I said, that’s what it was. So now we have this period to think about what happened. We got a little bit over the surgery of the nostalgia of we’re losing our youth, the Beatles broke up and I don’t think they’ll ever be united and I could care less. Jerry and Abbie don’t see each other much, you know. Well, it’s time to get through with depression and screw those old boring questions.

Rubin: But, along with what you say, there’s importance to preserving the good of our history…

Hoffman: Of course. The decade thing that you understand real good—and there’s someone before you that understands it much better. José Ortega y Gasset. He does the whole thing and the whole world in terms of generational revolt. He explains everything.

On top of all that I see the ’60s as America’s Renaissance period, the Golden Age. The greatest decade of the 20th century and a significant decade for the entire world. We stopped the empire.

Rubin: How?

Hoffman: The other night I saw Clare Boothe Luce, America’s dragon lady with bright wings. I lived through the great era of America—the ’50s. Both my America and hers climaxed with the execution of the Rosenbergs in the ’50s. America ruled the world, it had all the big bombs and it misused or didn’t know exactly what to do with them. No one force is supposed to rule the world. That’s why the Rosenbergs to me were great heroes, and I hope they tried to give secrets to the Russians (I would have), or whoever it was, and I hope there are some Rosenbergs over there in Russia doing their thing, because no one force is supposed to own the whole enchilada. So, it doesn’t matter what it’s called. The United States of Soviet, USSR, USA. I mean, it was fun when the Beatles mixed it all up. I think they came to this whole insight, and of course that’s one reason why this all happened. We had the Beatles and that was nice and fortunate. We had TV We had the methods of communications. We had a certain kind of shifting in our perception that occurred in the ’60s, and we had the climax and the fall of the American Empire. The quick rise and fall. It happened the moment the government threw the switch up in Sing-Sing: the quickest rise and fall in history.

Rubin: Why are there so many people in the ’70s who say that there were no results of the ’60s? The ’60s didn’t succeed and the world is either a bigger mess or nothing’s happening. What do you think?

Hoffman: They’re wrong. Just unhappy people. Back in the ’60s I said I missed the ’50s. It’s that kind of a thing. You heard me talk about the ’60s and it was all one big exhale. You can’t exhale forever. Did you ever try to do that? One whole decade of a big exhale. You’ve got to inhale. Well, the ’70s is an inhale. When I went into Mississippi in the early ’60s it was psychotherapy, and some people said you’re not supposed to use struggle and movements this way. Well, they were wrong. They were wrong because there is not that separation. The introspective period did occur in the early part of the ’60s for me. The ’60s lasted 13 years. I guess we got up to 1973. It was so good we got three extra years. There were people asking me all about it. Maybe that’s one reason why I got busted and took off. I got tired of people saying, “Are the ’60s over?” It was 1973 already. It was 1974. They kept asking, “Are the ’60s gone?” And meanwhile everybody was saying it was awful, yet wishing we were back in beads and saddles carrying Stop the War signs. What do they want it to keep coming back for?

Rubin: The questions about the ’60s drove you underground?

Hoffman: For instance, going to trial again, dealing with the same role over and over. Asking the same questions, not growing, not learning anything. Oh, that was such a burden. Whew! I mean, you know. I don’t have to tell you. You know. Sometimes I almost want to kiss those two narcs on the lips.

Rubin: So you went underground, in a sense, to escape being Abbie?

Hoffman: To escape being Media Abbie. The media came very close to destroying the real Abbie.

Rubin: Yeah, but you did it in an Abbie way. You kept a frame of reference of being a public outlaw. You actually continued the ’60s into the ’70s.

Hoffman: Well, it took me maybe a year of incubation, where I really had to learn lots and lots of other things to try and figure out exactly the kind of things that are a lot more important. And I might say this is a continuing process that doesn’t end, this sort of thing that I’m describing. But I did not want to reject my past. That’s why I’m against all conversions. I don’t think it is really a healthy sort of a thing, the idea of rejecting your past. You must integrate your past into not only your present but your future.

Rubin: And you?

Hoffman: Well, I’m obviously going to have more influence. One decision that I’ve come to is that I’m going to try and concentrate on truth more and politics less. That’s one thing. That’s one sort of New Year’s Revolution.

Rubin: What do you mean?

Hoffman: I think the process of politics as we know it in general involves lies. Lying is, of course, very intriguing to me. I’m all hung up in this because here I am on this truth kick and I am living a lie. I’m not Abbie Hoffman anymore. Although I love him very much, still have his good qualities, have eliminated some of his idiocies. And you know what?

Rubin: What?

Hoffman: I can beat him in tennis!

Rubin: If you were, say, 20 or 21 right now—a young radical man or woman—how would you express your political consciousness in the ’80s?

Hoffman: Well, at the beginning of the ’80s I would be asking a lot of questions—a lot of questions. I’d want to know a lot about what went on in the ’60s. I’d want to know the stories that weren’t told and the stories that were told. I’d question everything at the school: I’d want to know who discovered America, and I’d want to get 26 opinions on that. And I’d want to know answers to things like Is the CIA or the KGB lying about whether Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were spies? I’d want to know answers about who’s lying and who’s right about Three Mile Island. I’d want to know about why there are no blacks in high positions in the antinuclear movement. I’d want to know if it’s enough to have an Uncle Tom approach to the problems of oil and distribution by putting one worker on the board of General Motors.

Since this is an election year. I’d want to know an awful lot about truth and an awful lot about who’s telling the truth. And I would come to the conclusion that I’m going to study this election, because this is the most important event, both culturally and politically, that ever happened in the history of the United States. That the ’80s are going to be far greater than the ’60s, that the ’80s are going to be the second American revolution, whereas the ’60s were the second civil war. And I’d want to bring everybody together and say that everybody’s right! And I’d want to deal with people who are not going to tell any lies, ever!

Rubin: Who are you going to support in the 1980 election?

Hoffman: My first choice for president of the United States of America is the person I consider the greatest American lawyer in the country, and that happens to be Fidel Castro.

My second choice is the person—the American closest to my roots, to my birth, to where I was born. The name has great significance to me because it played a crucial role in the beginning of the ’60s, during which I certainly had a good time. And he’s a Boston Red Sox fan, and he’s running and he’s going to need some guidance and help, because he’s on the edge of life and he’s got a lot to think about. And that’s Ted Kennedy.

Rubin: Okay.

Hoffman: And my third choice—my third choice? That doesn’t work out! We get all the men in the country, see, and we line them all up and we pick the guy with the biggest bleep! Every politician, every candidate, is a fucking liar. That’s what it is—this country has to get out of lying! It has to get into telling the truth! If I was Ted Kennedy—and I tell you right now—I’m sitting here. When this magazine comes out, all right, and I’m sitting here a year ahead—a year ahead—and I’m telling you: Teddy Kennedy is already president.

Rubin: Right.

Hoffman: We have to live in the future. Now what do I give? Me, “outlaw” in the hills. What advice, after I’ve learned all those how-to-survives when everybody was chasing me and bookmakers said I couldn’t make it with my fucking big mouth and I’ve proved my point and I’ve learned my lesson? What do I say to Teddy? I say, “Teddy, hey, you know, you’re gonna need a lot of help to stay alive.” You know?

And why don’t you go to see Fidel and find out why he eats his own lobster? Why don’t you meet me in my home? Why don’t you come over and meet me for lunch someday? Find out how I cook, I’ll cook you a good meal, Ted. So, we’ll talk on… I’ll tell you about the time I ran a campaign against you, and we met in Worcester, and we’ll bullshit and talk about tennis, and I’ll come be in your tournament. I can beat anybody in your tournament in tennis. I’m great in any court: judicial, tennis, district, Sports Illustrated—it’s all in there, see, and that’s what the book is about. That’s what my movie is about. Excuse me, you see, because I said my—that’s not a good pronoun anymore. I don’t like that pronoun. I like we.

Sometimes, when I feel that everything is in the right position, I think about having a nice party. And I plan to advertise it—full-page ads! In magazines. And I plan to fingerprint it. And I’d say “Mr. & Mrs. Blank would like to invite you to their home for dinner. You know the way, just don’t bring any weapons.” And if Fred Silverman comes, he’s gonna have to bring a contract. And if Bob Dylan comes, he’s gonna have to bring Rod McKuen, and he’s gonna have to tell me why he keeps changing his name. I know why I keep changing my name.

Rubin: Do you think you’ll be aboveground in the ’80s?

Hoffman: That’s a possibility. You’re more concerned about above and below than me. ’Cause you don’t know the B personality. B’s friends don’t worry about me at all, my sanity, my betraying them. They need B. I owe them my life and I made a pledge two years ago that the FBI and no other force was going to remove me from the valley and my work. Not even Hollywood, nor all Abbie’s old friends. It’s just a whole new ball game. So, to quote a great ’60s philosopher, why don’t we end the bullshit questions and just DO IT!