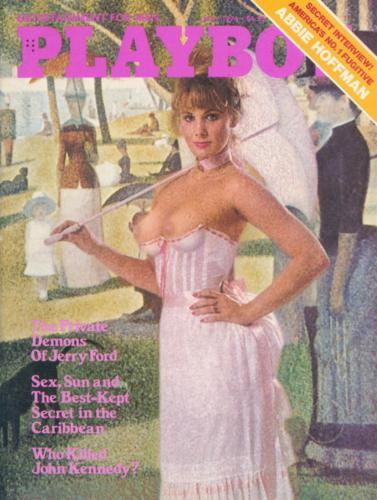

Playboy Interview: Abbie Hoffman

a clandestine conversation with the former yippie leader, now an "absent-minded" fugitive from a life sentence for dealing cocaine

He grew up a smart-assed pool shark in Worcester, Massachusetts, an industrial town famous for being only six miles from the birthplace of the pill. Most townfolk wish the pill had come first. After a checkered scholastic career that included spells at Brandeis and Berkeley, he returned to Massachusetts, where he tried to combine political activism with careers as a psychologist and a pharmaceuticals salesman; by then he had a wife, Sheila, and two young children to support. It was at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival that Hoffman first found himself on the wrong side of a policeman's truncheon--a position he would assume many times over the next decade. He joined the civil-rights movement and spent three years in Mississippi and Georgia alternately fighting off the Ku Klux Klan and trying to register blacks to vote.

After experimenting with LSD and divorcing his wife, Hoffman moved to New York City, where a new culture was breeding on the Lower East Side led by a gang of crazy long-hairs who called themselves Diggers and who believed in giving away everything they could lay their hands on, which, given their nimble fingers, was a lot. These, Hoffman knew, were his people and he emerged as the spokesman for this new class.

Another middle-class refugee, Jerry Rubin, was hanging out on the Lower East Side about then. When Rubin met Hoffman, the Sixties' most famous radical partnership was formed. The pair formalized their association into the Youth International Party--the Yippies--and made plans to invade the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago for a "Festival of Life." Thanks to Mayor Richard Daley and Chicago's finest, something quite different was in store for the demonstrators. Seven months after the convention and its disorders, Hoffman, Rubin and five other white radicals (plus black activist Bobby Seale, whose case was later severed) found themselves indicted under a new law--conspiracy to cross state lines to commit riot--by a new U.S. Attorney General, John N. Mitchell.

The trial of the Chicago Seven, as the group came to be known, symbolized the violent climax to the decade that spawned the generation gap. When, after one of the most controversial trials of the century, five of the seven were convicted--not for conspiracy but for individual "over acts"--thousands of young people took to the campuses and the streets to burn R.O.T.C. buildings and trash business districts throughout America.

In 1971, Hoffman found himself once more arrested, this time for his participation in the May Day demonstrations in Washington. New trends were rocking the antiwar movement. One declared that leadership was inherently evil. Another, backed by the emerging women's movement, hurled charges of elitism and male chauvinism at virtually every white male movement personality. Exiled from his constituency, Hoffman wrote an open letter "resigning" from the movement. He turned to other things. In 1970, he had helped spirit LSD prophet Timothy Leary out of the country to take refuge with Eldridge Cleaver in Algeria. Cleaver, Leary and companions fell out, but Hoffman decided to collect in written form what he had learned from that experience and add to it other forms of outlaw how-to know-how. Although he had achieved commercial success with two previous books, "Revolution for the Hell of It" and "Woodstock Nation," he could find no publisher willing to produce "Steal This Book"--not under that title, anyway. So Hoffman published it himself and "Steal This Book" became an underground classic.

The pressures of police harassment, media overexposure and constant needling from the left had driven Hoffman and his new wife, Anita, to seek a life of seclusion. So with the arrival of his son, america, Hoffman decided to cool his heels, play family man--and write a sequel to "Steal This Book" that would take everything one step further. In August 1973, during the preparation of the book, he arranged a cocaine sale through contacts he says he made for research purposes. With three others, he was arrested in New York's Hotel Diplomat and charged with the sale of cocaine, conviction for which would mean a mandatory life sentence. After spending six weeks in the infamous Tombs prison, Hoffman was released on bail--and resolved he never would spend another minute in jail. In October of that year, he appeared in court in Chicago; although the court of appeals had struck down the Chicago Seven's conviction for incitement to riot, it ordered another trial on charges of contempt of court. Hoffman and his codefendants had never hesitated to express their outrage against septuagenarian Judge Julius Hoffman, who had presided over the original trial. Once more Hoffman was convicted but was not sentenced to a jail term. That, however, was to be one of the last public appearances for Abbie Hoffman. In March of 1974, he vanished and shortly thereafter sent word that he intended to remain a fugitive, dedicated to building an underground network of armed subversion against the Government of the United States. He has since undergone plastic surgery to alter his appearance and, except for a video taping done a year ago for public television that resulted in an article in New Times, this is the first major interview he has granted since that time. Ken Kelley, a free-lance writer with underground connections, contacted us with the possibility of conducting an interview with the man who, since the capture of Patricia Hearst, has become the FBI's most wanted radical fugitive. The story of how Kelley pulled it off appears on page 67.

[Q] Playboy: Why did you decide to risk doing this interview?

[A] Hoffman: It was a collective decision. And the fact is, I read Playboy--but only for the recipes. Family Circle tells you how to make frankfurters in aspic, but Playboy has very sensuous recipes.

[Q] Playboy: So you're a chef as well as a radical fugitive?

[A] Hoffman: Yeah, if you can make a bomb, you should also be able to make a soufflé. Even if you can't spell it.

[Q] Playboy: Have you been making bombs in your new life?

[A] Hoffman: Bombs? Boom-boom? I've never gone bombing. They wouldn't let me come. I belong to an organization and if I do anything important, I check with the division commander. I'm no anarchist, you know.

[Q] Playboy: There are risks in having this conversation, though, aren't there?

[A] Hoffman: Sure, especially because in the small town I live in, people read Playboy--and some of the stories I'll be telling in this interview might be recognized by them. The other thing is that the magazine is clearly taking a risk. Playboy is, in effect, saying that it won't cooperate with the Government in its attempt to capture and cage me. Hugh is putting his ass on the line, no doubt about it. I think it's very brave and courageous.

[Q] Playboy: Let's start with your arrest for dealing cocaine. Why did you decide to go underground rather than fight the charges against you?

[A] Hoffman: We didn't have the time, we didn't have the money to put on an adequate defense. I guess the odds are probably two to one that I could have won the case, but if I'd lost, the penalty was a mandatory life sentence. Mandatory! That means there weren't even any options. It's the same as if it were a murder case. I didn't think the best way to carry out of my goals in life would be to spend the rest of my days in a Rockefeller resort like Attica.

[Q] Playboy: Were you guilty of dealing cocaine?

[A] Hoffman: Well, not in the way that you and I'd use the term dealing. It wasn't my dope. I mean, I played a role--I arranged for two cops to meet each other, but I was set up by them, and besides, they used illegal wire tapping and entry. That was attested to in open court by impartial witnesses, and the transcripts show it. So the answer to your question is no, I was not guilty.

[Q] Playboy: If what you say is true and the transcripts contain that evidence, why haven't the charges against you been dropped?

[A] Hoffman: Without public support, I can't win the case. The hearings have shown that the police committed perjury. Impartial witnesses identified these cops, these same cops that busted me, as the ones who illegally wire-tapped and entered the apartment I was in. However, there is no guarantee that this could be presented in the trial. The courts have to work with the police all the time; the police have incredible resources and power. The rules of evidence, misconceptions about dope, my revolutionary views--none of these help. If it had been an average case, the charges would have been dropped a long time ago. But I haven't been involved in an average case in a dozen years, because every arrest has had political overtones. Political cases have to be fought in the public arena. The district attorney held five press conferences within the first four days after I was busted, announcing that there was nothing unusual about this case.

[Q] Playboy: What were you doing at the time you were busted?

[A] Hoffman: Actually, I was planning the breakout of a friend from Rahway prison in New Jersey. Nothing more on that--I don't want to blow his chances for trying again. I was working on a book about crime I was going to call Book-of-the-Month Club Selection, which would include all sorts of stuff on underworld people, dealers, bank robbers. Ironically, I was also giving speeches on Rockefeller's drug laws, which went into effect four days after I was busted. The New York drug laws are the harshest in the country. If you're found guilty, you're eligible for parole in 15 to 25 years. There are rewards for people to turn in their friends.

[A] Anyway, I had been interviewing dope dealers. I wanted to include a chapter on cocaine, because it was in fashion, you know, and I didn't think it was particularly harmful: Medical research has only proved that it scours your sinuses. If you examine its history, it's been used by blacks a lot, so of course it has been illegal for about 60 years--to get blacks into jail. So one of the dealers turns out to be a cop, which I didn't know at the time. I'd known this person since the Columbia demonstrations of '68--he was probably a cop then, too--and I saw him occasionally. His name is Louie. In the course of telling me about cocaine dealing, he asked if I knew anyone interested in buying it. And, in asking around, I discovered a few people who decided to pool their resources. I brought the scale and we went down to the Hotel Diplomat--I was to get a tip for being the scale bearer. Anyway, instead of Louie, up popped 30 cops through the wallpaper, shouting, "We got your ass now!" and similar cop childishnesses. I felt real bad.

[A] As soon as I was in the slam, bail was set at $200,000. Then, later, it was cut in half and eventually I only had to post $10,000 because I followed my lawyer's advice and didn't run off at the mouth. If you play their game and don't say anything nasty, just keep quiet and look at your shoes, the bail goes down--if not, as was the case with the Panthers, bail stays up and you stay in. Of course, my silence added to the presumption of guilt.

[Q] Playboy: You were locked up for six weeks before bail was posted, weren't you?

[A] Hoffman: Yes, in the Tombs in Manhattan during the hottest summer in New York history. I was placed in the administrative ward--that's murder and up--for my own "protection." It was so hot everyone soaked towels in the toilets and wrapped them around themselves. There was no air. And I couldn't eat for six days, because the food was so miserable. There were rats in the bread. In front of my cell, a guy got his eye ripped out of its socket. People are turned into animals. I developed the not-unrealistic fear of homosexual rape after being stalked. It's built into the system, the control mechanism. I made up my mind that if I could get out, nothing would ever get me back.

[Q] Playboy: How much cocaine did they find in the hotel room?

[A] Hoffman: Three pounds.

[Q] Playboy: And you claim you were there only to observe and take notes for your book?

[A] Hoffman: And to referee, to arrange the meeting.

[Q] Playboy: Come on; why would you go to all that trouble for research and a tip?

[A] Hoffman: That's the only thing I'm ashamed of--that I got money for it. In my mind, doing anything for profit is evil, so that even if I was set up, I felt both guilty and innocent. It got pretty complicated, morally. I don't know if I'm innocent or guilty. All I know is that I was to be an example. To be a dealer. as they know it, I would have to have had Mafia connections. I don't know that area. I don't even know the marijuana empire.

[A] But if I'm considered guilty, then the police are, too. We had affidavits attesting to the fact that the cops entered my mother-in-law's house illegally, posing as workers for the phone company. A cop who was instrumental in the bust was recognized by a witness as one of the "telephone-company men." There are tapes, too, which the cops made: The room had been bugged. Even my prosecutor didn't believe the police. But he was one of the guys in the D.A.'s office who wanted to make it big. Meanwhile, the cops who had done the bugging "vanished" and my lawyers couldn't get hold of them. The official excuse for the vanishing was that we'd be gunning for them. When the court asked the CIA for its files on me, the CIA came back with something to the effect that it had never heard of me. It admitted to having files on 10,000 radicals, but not on me. Meanwhile, the judge, a kindly black lady, seemed to want to give me a good chance--to do a Sirica--but with all those witnesses testifying to wire tapping and those two cops lying, she had to choose and she chose the cops. Of course, judges have to work with cops every day; it's a rare judge who will go against them in such circumstances.

[Q] Playboy: Were there other attempts at setups?

[A] Hoffman: Well, in the Tombs, I met this guy who tried to talk to me about jumping bail and escaping through his connection to Argentina. Instinctively, I didn't trust this guy. It seemed to me that he might be another planted informer, who could testily that I was making Plans to jump bail, which meant my bail would be revoked and I'd be wearing handcuffs throughout the trial. I was warned by a lawyer that the D.A.'s office might try something like that. The tactic is to make you so skittish that you land in jail for thinking about escaping.

[Q] Playboy: You were thinking about it, weren't you?

[A] Hoffman: Sure. Once I was out. I talked with a friend who had been in Attica and I knew I would end up being bumped off. That's not theoretical, either. I would have been killed in Attica--no doubt about it. I was having nightmares all during that time. I had dreams about being gunned down by the piggy sheriff in the Dodge ads.

[Q] Playboy: Had you considered the possibility of going underground before your cocaine bust?

[A] Hoffman: Yes. I had always considered it an honor to harbor any fugitive. Now I was on the other side, Potentially. I decided to try a dry run in 1971 and I toured the island of St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands with a false identity card. Here I am, and I've rented a house and put a deposit on it, and I come out to my rented car and there's this meter maid, a short little lady, putting a ticket on it--the meter has run out. Like a jerk, I stick my nose in it and she says, "Excuse me, could I see your licenser" So I show her my license, but she wants some special license they hand tourists and which I haven't got, and she arrests me. She's steering me gently to the police station, which is conveniently only about 40 feet away, and when I get there, I'm more under arrest than ever. I can get out for a $100 bail fee, only I don't have $100. I'm on bail at the time, and a violation is 10, 20, 30 years in a case like that. Then they say, "OK, court is in session." The judge's name is Hoffman. I think, "God, it's only a year and a half after the Chicago trial, has Julius Hoffman retired here?" So I walk in, trying to look like a six-foot-two-inch blond Italian, and this Judge Hoffman is black. I walk up to the bench sideways and talk in an altered voice. He says it's a five-dollar fine and the tourist agency's fault. Later, I find out it is perfectly legal to live in a U.S. colony assuming an alias--you can use an alias as long as it's not for purposes of fraud. But I was surveyed constantly. Once the news broke that I was there, the local police decided that I was there to stir up the blacks. Actually, that was the real changing-the-diapers period.

[Q] Playboy: What were the first preparations you made to go underground?

[A] Hoffman: Well, it seemed like I had been preparing for a long time before the actual idea occurred to me. My background gave me some idea about political asylum that a person like Patricia Hearst, for example, couldn't have. I had investigated the political-asylum angle for other people, so I knew the practical and psychological areas. It seemed to me that Algeria, where I had helped bundle Learn off to, was inhospitable; a person was liable to end up under house arrest or charged with the use of narcotics there. The exile community itself was unstable--such as Learn himself, who got off the plane in Algeria to take a leak and told everyone where he was going so he could get fan letters. I never have favored asylum in the long run. Exiles get cut off from the struggle. They end up getting dislocated, like all those 19th Century Russian anarchists hanging around Zurich bleeding for a bowl of borsch. If an exile sees something wrong happening, he's helpless. In the FBI's eyes, you are like a sore nerve ending; you can expose the presence of the CIA just by being there. So they want you liquidated. It's difficult to tell how sincere a country that takes in exiles really is--Israel has this big mother myth of itself as refuge for all Jews in trouble, but I wouldn't be worth threatening negotiations over a Phantom jet.

[Q] Playboy: You mean you considered Israel as a possible asylum?

[A] Hoffman: Nah, I don't believe in a religious state. I'm a Communist. To say that every Jew should support Israel is like saying every Catholic should have supported Mussolini's Italy. Well, fuck that. But Jews are interesting people--we were chosen, after all. But chosen to do what? There are two kinds of Jews in the world: the kind that go for broke and the kind that go for the money. Those who go for broke say crazy things like, "Every kid wants to fuck his mother," or "Workers of the world, unite." Jewish troublemakers. That's the creative, humanistic trend in Judaism, but there's another: "Don't rock the boat." It fucked up my childhood. But I've gotten some perspective on it now. In my new life, people don't know I'm Jewish--you notice I don't look Jewish!--and I sometimes hear anti-Semitic jokes I never heard before.

[Q] Playboy: What other identities did you consider?

[A] Hoffman: Well, I thought about becoming an Italian. I was told I'd have friends in Sicily, no questions asked. And, of course, a year ago at Christmas I was Mickey Mouse at Disney World.

[Q] Playboy: You look as if the experience aged you.

[A] Hoffman: No, that's the plastic surgery. A woman I lived with told me that now I look like the normal Abbie Hoffman--but handsomer. So it has its Cinderella aspect, you know. Your face changes, you have to be different all the way through. I trained myself to change my eye movements--I used to make eye contact with everyone; now I know how to glaze over, keep preoccupied. I learned karate to change my gait, losing ten pounds in the process. Being away from Anita changed things, too--if you have to keep in touch with someone through a complex letter system, it changes things.

[Q] Playboy: What was the plastic surgery like?

[A] Hoffman: Well, it started out kinda freaky. I wanted the doctors to age me, which shocked them enough to land me in a loony bin right there. The whole world wants to look younger and this creep walks in and says, "Wrinkle me up, man!" I told them that I was doing a TV series in Canada for children, playing the part of some grandfatherly old shit--like Captain Kangaroo--and they believed it, fortunately. Hospitals are interesting, because the level of conversation is always, "Hi, sweetie, you've got the best doctor in the whole wide world and there's nothing to worry about"--even though they don't give a fuck about anything but Blue Cross. The cops didn't intervene, because, at the time, I was not yet a fugitive. I could have had a vaginal cyst for all they knew. Anyway, they pumped me up with Demerol and I got high on changing my face. You give the doctor enough money and you can be tall, short, he'll take something out, put something in. So now I have one nice Aryan nose, rosy Anglo cheeks. And for further changes, I had learned about make-up for television appearances. I'd been doing fucking research for three years.

[Q] Playboy: All this was happening before you officially became a fugitive?

[A] Hoffman: Yeah, the judge is taking her time, thinking I'll show up because she's playing Sirica while playing footsie with the cops. Meanwhile, I'm trying everything out--except for drag; I don't think I could have worked in drag.

[Q] Playboy: But just to stay on the track, when exactly did you make the decision to go underground?

[A] Hoffman: When I was in Mexico City. Dick Cavett didn't know it, but he paid for my escape. Cavett contacted me and sent me a ticket when I was on his show. It was made out in my name from Mexico City to New York to Richmond to Atlanta to "void." The ticket was open-ended, in other words, so I could keep moving. And the South seemed a good place to vanish, once I started thinking about it. I figured I'd catch the Allman Brothers' show in Atlanta, then fade out from there. I gave my last public speech at the University of Richmond after I'd made up my mind. I didn't know where I was going, but I knew I wasn't coming back. It was a good speech and I put in a clue that I was splitting. I said, "Tell Rocky when he comes looking that he ain't ever gonna find me."

[Q] Playboy: Aside from the plastic surgery, how did you change your physical appearance?

[A] Hoffman: I started talking with this cab-driver in Atlanta who was getting his hair conked. The idea occurred to me, "Goodbye, famous frizzy hair." I decided that if I had only one life, I would rather live it as a blonde. Blondes have more fun, right? Back in my hotel room, I slathered my hair--and my snatch--with Clairol, half-blinding myself in the process; those fumes nearly killed me. After the chemical ordeal, I went to the mirror, expecting to look as Nordic as Veronica Lake--but nothing had changed. My hair was still brown. My hair was still frizzy. I looked at the instructions on the package. I had followed them exactly. It seemed my body was just not going to take that shit sitting down. So certain things didn't work.

[Q] Playboy: Well, you don't look like the same person now.

[A] Hoffman: Yeah, that pleases me. I'm a new face and I've got my clothes all changed and everything. All those "Wanted" posters come out, and I paste them up all over the mirror and say, "I don't know who the fuck you are." But for a while, it was strange. Plastic surgery hurts. I didn't believe anything but the pain for a while. It took me three weeks to recover. There's no accurate way of telling if you have changed as much as you think you have. Recovering in New Mexico, I ran into this kid I could have sworn recognized me from some campus organizing I had done or something. I tried to bluff it, but I am sure he knew. Probably I just smelled like Abbie Hoffman.

[Q] Playboy: Was the surgery expensive?

[A] Hoffman: Absolutely. But the doctor hurt me, so I skipped out. Blue Cross doesn't pay for that kind of thing.

[Q] Playboy: How did you and Anita face the prospect of separating?

[A] Hoffman: At first, we were so busy getting mobilized, in kind of a trance, nothing really hit us. When it did, we just cried. Nothing is as intimate as crying with someone--not loving, not balling. One of the hardest things was my kid, america, who I won't see grow up. My kid became the symbol of everything that would be missed. I became really pensive. I had to look at everything. But once I started to go, it was a question of mechanics.

[Q] Playboy: What did you do in your first months as a fugitive?

[A] Hoffman: Well, for six months I worked (continued on page 72) as a teacher. I was very even, very disciplined, very tight. Everyone kept telling me that after six months it would be cool, so I played Mrs. Grundy and kept kids from gouging each other's eyes out with Ticonderoga pencils. No one could eat the crayons. Everyone went to the bathroom only after raising his hand. But they were the loneliest months of my life. I didn't talk to anyone. Then a crazy lady fell in love with me. She was a Catholic, so I had to go Catholic pretty quick. I went to church every Sunday for five weeks and didn't blow it once. I tell you, I genuflect like a pro. Finally, I began to make my way into the world very, very delicately, all my feelers out. I made new friends who didn't know who I was.

[A] For caution's sake, I vanished several times and re-emerged elsewhere, using another name and identity apparatus. Then there was always the fear that someone who had known me in my last false incarnation would walk up and call me Ted when I was now David. There's no way of shutting up an insistent acquaintance quickly--no little flip of the thumb that means "Cut it out; it's urgent"--so I would just have to be on the lookout without seeming to be. If you look paranoid, you bring things on your ass. So there was always a question of the fine balance.

[Q] Playboy: Have you seen old friends since you've been under?

[A] Hoffman: Oh, yes, but not as Abbie Hoffman. I have talked with very old friends without their catching on--it was like being at your own funeral. But it was necessary. Occasionally, I have visitors from the past, but it throws me off pattern. If I take an old friend to a party, he's so uptight about blowing my cover that he usually ends up in the bathroom trying to vomit up that one beer that might have loosened his tongue. Friends from the past have to make all the adjustments too quickly. They think they might call me by the right name. The wrong-right name, I mean. See how confusing it gets? It actually happened once, but no one noticed. But they always feel everyone knows. They read signals where there are no signals. I keep it down to a minimum because it's hard on everyone.

[Q] Playboy: Have your friends and family been harassed by the FBI?

[A] Hoffman: Anita has been turned into a surrogate black widow: Every time she goes on a date, they jump the guy. They're trying to isolate her to the point of craziness. They've smashed communes--anyplace they think I may have been gets some kind of ugly attention. Hell, they tried to stop my father's will; they tried to keep everything in escrow. My brother inherited the business and I was left $1000--but they tried to keep the will from taking effect, as if that would smoke me out. They're all over the place.

[Q] Playboy: How competent does the FBI seem to you from your perspective?

[A] Hoffman: It is a good deal less active than you'd think from watching Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., bagging his man once a week on television. But they can make it hard on you, anyway. If someone like me--aged 39--tries to get a job, a longtime résumé is hard to forge. They also assume that you will resume past contacts--one of whom is bound to be an agent. Or they think that word will get around, that they've infiltrated the left so deeply that they'll soon pick up information and crack your web.

[A] I assume that in my case they have at least a couple of goons after me permanently, because it is important enough to reach the newspapers and they will get a lot of mileage out of that. They were really boosted by nailing Patty Hearst. The FBI never looked so good. She's not dead, they've got her and all the others--excluding the ones they killed--and it took the heat off. The FBI was looking incompetent for a while and it was hurting the budget, not to mention the big macho myth dear to the heart of every Amurrican. The Patty Hearst case allowed them to learn a lot about fugitive life.

[Q] Playboy: Do you move around as much as Patty Hearst did?

[A] Hoffman: I'm not as athletic. I'm more domestic. I probably move around less than you do. I heard the average American moves every two years. I've lived as long as eight or nine months in the same spot, with intermittent periods of travel. I've been in almost every state of the Union--except New York. I could get into New York and out, I know exactly how to do it. I almost did a video-tape thing of me defying the police to shut me out, but I decided it was a little banal. And though I am sure I can get away with it, it almost tempts fate. I want to maintain courteous relations with fate.

[Q] Playboy: Did the S.L.A. experience teach you anything about your own life as an outlaw?

[A] Hoffman: Yes--that you aren't going to scare the masses into a revolution in the U.S.A. Revolutionary violence has to be very precise--like a scalpel. It has to be used very delicately and it has to be used against objects that are seen as evil by a broad enough range of people. The most important object of an underground revolutionary group is survival, not to get caught. The S.L.A. would have been better off sitting on its collective ass for six years and not doing anything. Its survival would have been a revolutionary act. But then it blew it when it started militant actions of a dubious nature--like killing a black superintendent. I used to have this out with black revolutionary groups all the time in New York, you know, about shooting a black cop. If you shoot a cop, shoot a white cop. Shooting a black cop just sharpens distinctions. With revolutionary violence, you don't just go off and shoot the mailman because your welfare check didn't come on time. With revolutionary violence, you attack the enemy. The enemy is defined as the enemy of all people. Your bombs and your bullets had better be well placed--toward the ruling class. Now, should radicals bomb the Pentagon, that has a different quality. But I don't put the S.L.A. down the way the Panthers did.

[Q] Playboy: Did you have any close calls when the FBI was hunting for Patty Hearst?

[A] Hoffman: Patty had me on the move more than anyone else--certainly more than the law. There was a lot of knocking on doors, with agents asking if anyone was moving in--things like that. I'd pick up the paper and it would say that Patty was rumored to be near where I was. Everywhere I went, Patty was on the same block and I'd think, "Oh, God, she's living next door--I've gotta split." I'd think, "Oy, she's gotta come here! Who needs this? I got enough problems." If necessary, though, I figured I might be able to take some heat off her--if there are 50,000 looking for her, maybe I'm enough to divert 10,000 of them. I would have helped her--there's no question about that. I have never not helped a fugitive--and I'm not saying this because I'm a fugitive now. Fugitives are my kind of people. They sleep in closets. They read all the time. They never argue. They don't try to piss people off. I know I try to be good company--I make my hosts feel good by entertaining them, cooking good food.

[Q] Playboy: Did you ever meet Patty Hearst?

[A] Hoffman: Not knowingly. When I was in California, I went to the Hearst castle, San Simeon. My friend Angel took a picture of me in a big funny hat waving Hi, baby, hi, hi, hi to Patty. I sent it to her through the media. That's how you communicate, because we all watch the same television shows.

[Q] Playboy: Angel is the pseudonym of the woman you've been living with. Tell us about her.

[A] Hoffman: I've been very lucky. She's an exciting, interesting companion. I met her after I went underground, and if I'd taken someone with me--there were offers from people who wanted to go--I'd have chosen badly. I was filled with anxiety and fucked up.

[Q] Playboy: Did she know who you were?

[A] Hoffman: From the beginning. But it's not natural for her to call me Abbie--I'm Brian to her. It's absolutely not natural for her to think of that other person.

[Q] Playboy: Why did you decide not to go under with Anita?

[A] Hoffman: I don't make her decisions, and we decided together that this life would be too dangerous for our son, america. The separation has been less painful than you'd imagine, because my friends and comrades have stepped in to fill the void.

[Q] Playboy: In your communications with Anita, have you found out how your son is taking it?

[A] Hoffman: He understands he was not abandoned; we were driven apart by the Government.

[Q] Playboy: What is the closest you and Angel have come to being caught?

[A] Hoffman: Once I was driving a car with Angel asleep in the back seat and I was stopped for speeding. The cop asked me a bunch of questions about the I.D. I was carrying. I knew all the dates and everything, but I hadn't been sleeping well and I was a little slow. So the cop says he wants to wake up Angel and ask her some questions while I stand off to the side. I knew he wanted to see if her story jibed with mine and I was really nervous. He had a loaded shotgun mounted in his car and I was wrestling with the possibility of grabbing the shotgun if he came at me, because I couldn't let him get the handcuffs on me. But she told the story all right and it worked out. Actually, once I was arrested for a charge more serious than traffic.

[Q] Playboy: What was that?

[A] Hoffman: Dope. Party dope. I was with a group that got busted and somehow I just talked my way out of it. I didn't know what I was saying.

[Q] Playboy: How, in fact, do you support yourself? Where do you get money to rent cars, to feed yourself, and so on?

[A] Hoffman: At the beginning, I had some people who helped me out financially, and I had some funds of my own--maybe $5000 or $6000 from articles I'd written. But, on occasion, I've been close to desperation. And I have engaged in illegal activities.

[Q] Playboy: Such as?

[A] Hoffman: Low-level, teeny-bopper white crime. Traveler's checks, stuff of that nature.

[Q] Playboy: Do you shoplift?

[A] Hoffman: Yes. I don't steal socks from sporting-goods stores in Los Angeles, backed up by a chorus of machine guns, I'll tell you that. But there have been times I've let my fingers do the walking.

[Q] Playboy: What about cash?

[A] Hoffman: Yeah, that's always a problem. I like to have a certain amount of money on me, in case I have to bribe a cop. That sometimes works.

[Q] Playboy: It does?

[A] Hoffman: They are not above corruption, young man.

[Q] Playboy: Aren't you worried that something as relatively insignificant as shoplifting could get you caught?

[A] Hoffman: I have to survive and it's very hard at my age to get hired for a job and I'm pretty good at shoplifting. Actually, I got forced into it by a repressive, puritanical society. When I was very little, I had to swipe dirty books, because I was ashamed to buy them: 48-year-old teenagers with huge boobs and he cupped her breasts in his hands and felt her inner thigh, higher, higher ... which was enough in those days. So sex and theft are highly correlated in my life.

[Q] Playboy: But you haven't often been close to desperation, have you?

[A] Hoffman: No. I have a lifestyle I would term primitive elegance.

[Q] Playboy: You make it sound like great fun. Has it been?

[A] Hoffman: No. You've known me from the past, so when we meet, you're more or less seeing the old me. But if you were to observe me through a one-way mirror as I interact with my new friends, you'd see a different person--maybe several different persons. And packing too many identities into your head at once can become very difficult. At the beginning, when people would press me for information, I'd introduce a tremendous personal tragedy--such as my parents getting killed in a car crash. It would stop the questioning. But I can't always remember what my newest story is. People will come up to me and say, "It's a shame your mother died in Calcutta," and I have to say to myself, "Let's see ..." I've told other stories, but I'm trying to be selective, picking stories about people who won't read Playboy. It can get confusing. In fact, once I cracked.

[Q] Playboy: How did it happen?

[A] Hoffman: I did this taped interview for public television, but I was only impersonating myself; it wasn't real. I said on the tape that I was together, I was pretty healthy. But, in fact, I went right out and cracked, really flipped out. Knowing the U.S. as I do, I had the good sense to head for Las Vegas. I knew I was cracking and I said to myself, "Don't go near the tables, don't go near the tables--you crack there and they'll call the cops." I figured upstairs would be all right--you could be moaning and crying in a corner of an elevator and everybody would assume you'd just lost your business at the crap tables. So I managed to get into a hotel room and then let go. I ripped the furniture apart. I screamed out who I was--Abbie Hoffman!--all over the place. Once, I was standing next to Mort Sahl, who didn't recognize me, and I kept yelling things like, "Play Red!" and "This is all going to Bangladesh!" I talked for 52 straight hours, until my lips were all cracked. For a few days, Angel and I got into the car and just drove through the desert. I kept hallucinating that she was Patty Hearst--and I had my doubts as to who I was. Luckily, Angel was a good soldier and knew how to deal with it. She got me some tranquilizers, which I wouldn't swallow at first, because I was fantasizing that they were poison. But finally I cooled out. Health food, no meat and a secure environment for a couple of weeks and I was OK.

[Q] Playboy: Could you flip out again?

[A] Hoffman: No. No. That caught me by surprise. I can't answer the question. I don't know. Life is full of surprises. I don't know.

[Q] Playboy: Was that the only time the identity switching got to you?

[A] Hoffman: Yes. After two years, these changes aren't very awkward. I have several levels of identity. Like now I'm Abbie, but if a friend came into this room who knew me as Brian, I'd be Abbie and Brian both, and when you leave, I'll be all Brian--except for what I write and lock in the trunk. It gives me an exhilaration and confidence to realize I can move from one role to another.

[Q] Playboy: You seem to be saying that in one sense you're freer now than you were before.

[A] Hoffman: Well, my phone isn't tapped for the first time in 15 years. I'm not under surveillance by three or four agencies. There's a difference between being hunted and being watched. Most people think it's the same, but it's very different.

[Q] Playboy: Let's talk a little about those 15 years. Can you retrace the steps that led you into activism?

[A] Hoffman: My father always blamed Brandeis.

[Q] Playboy: Do you?

[A] Hoffman: Nah. Even back in high school, grade school, I was generally the wise guy in the class, the troublemaker. I was too smart for my own good; if I had had some right teachers, it might have ended up differently. But the teaching was abominable. Biology teachers who would tell you they knew by looking in your eyes whether you'd masturbated that night. An English teacher who used expressions like "There's no niggers in the woodpile," and, of course, the only black in school was in the class. He was class president. One of your basic beiges.

[Q] Playboy: Have you ever gone back to Worcester?

[A] Hoffman: Oh, sure. I even spoke at Holy Cross College and there was a huge turnout. You know, local boy makes bad.

[Q] Playboy: Did you get into any serious trouble in high school?

[A] Hoffman: I was kicked out. I sent that in on my Who's Who questionnaire, that I was the only Jew expelled from Classical High School?

[Q] Playboy: Did they publish it?

[A] Hoffman: No, just all the good shit.

[Q] Playboy: Why were you expelled from school?

[A] Hoffman: There had been a series of incidents--smoking in the boys' room, stuff like that. The final kicker was that, for English class, I wrote a very serious piece about why God doesn't exist. I was real proud of it. My teacher takes it home to read and he comes back and he goes crazy. Starts shaking me and rips the piece up. I'm really pissed and we start fighting. The other teachers had to pull me off. "Hoffie, that's it for you," they said. "Out."

[A] After about a year, my parents felt my career as a bum, hanging around pool halls and bowling alleys, didn't look good in the Jewish community, so they got me into a private school. And then I went to Brandeis. Brandeis and I were ideally suited. In 1955, it was seven years old, and that was about my psychological age. There were tons of great teachers, radical for that time, at Brandeis--Abe Maslow, who was my psychology guru; Herbert Marcuse; Frank Manuel.

[Q] Playboy: You were in college well before the campus radicalism of the Sixties, then.

[A] Hoffman: Oh, yeah, the issues were different. There was the famous door-gap crisis: How wide should a girl leave the door open in the dorm when she was having a boy in? Each year you could trace how closed the door got, you know what I mean? Finally, by my senior year, they allowed you to have the door closed for four hours on a Sunday, and the boy and girl were allowed to be in bed. Now, of course, it's all reversed. The college wants you to close the door and everybody's leaving his door open and fucking and sucking.

[A] Anyway, I finished at Brandeis and went to Berkeley, to study psychology in graduate school at the University of California. And that's where I went to my first demonstration.

[Q] Playboy: Was that part of Mario Savio's Free Speech Movement?

[A] Hoffman: No, Mario came along later, in 1964, but that protest was really set in motion by the one I'm talking about, which took place in May 1960. It was a silent vigil protesting the pending execution of Caryl Chessman. Chessman had been on death row in San Quentin for 12 years; he had become a symbol of the battle against capital punishment. He had been convicted of being a flashlight rapist; he allegedly would jump girls in the dark, put a flashlight in their face and tell them to blow him. One of these women went nuts. There were no deaths involved in these flashlight blow jobs, but he was sentenced to death.

[Q] Playboy: What happened at the demonstration?

[A] Hoffman: We all stood outside the walls of San Quentin; a bunch of students, some celebrities: Shirley MacLaine, Marlon Brando. We carried signs: Thou Shalt not kill. I remember the warden of the prison came out and served us coffee and doughnuts and gave a speech: He didn't believe in capital punishment. The governor, Pat Brown, leading liberal of his time and father of the present governor of California, was saying he didn't believe in capital punishment. Nobody there believed in capital punishment. And at ten in the morning, they're in the gas chamber reading prayers: "May God rest his soul." We went back to Berkeley stunned; it led us to wonder how things like that could come about in a democracy, when nobody wanted that person to die. The wheels of society were set in motion and he died. Nobody could stop them.

[Q] Playboy: What came next?

[A] Hoffman: Well, the House Un-American Activities Committee went to San Francisco for one of its Red witch-hunts, and there were street riots and police stompings and clubbings. For someone educated in the American style who had never even heard of Sacco and Vanzetti--even though the trial was held in my home state--it was a revelation. I had never heard of the Rosenbergs, except that the whole thing was bad for the Jews. I wasn't even taught in high school that there was a Depression in this country in the Thirties, or about the Civil War and about the slaves. Nothing about Joe Hill, Bill Haywood, feminists, abolitionists, none of that. John Brown was a lunatic and Dwight Eisenhower was Abraham; that's the education I got. I never knew about the Japanese internment camps or any of that stuff. America stood for truth and justice and anybody can grow up to be President, and it was the greatest country in the world, expiring from God's brow. Then to see those people being persecuted by HUAC for their beliefs!

[Q] Playboy: What triggered the riots?

[A] Hoffman: What really pissed everybody off was that it was supposed to be a public hearing and people started lining up at dawn and found they couldn't get in; the committee had passed out little white cards to members of the D.A.R. and the American Legion--they were the public. People started pushing and yelling "Down with HUAC," so the San Francisco goon squad was called in. It was a horror show. They used water hoses and rapped heads and they had a thing called the knee bender. They'd put one handcuff on your wrist and turn it once and you're on your knees; a second turn and it breaks your wristbone. After I left Berkeley, when I was back in Massachusetts working as a psychologist at Worcester State Hospital, I saw a movie the Government had made of that incident, showing how it had all been perpetrated by Communists. I was furious. I jabbed a pen through my hand I was so angry. I challenged it from the audience. "I was there!" I yelled. The next day, the local representative from the A.C.L.U. called me and asked if I'd be willing to go on tour with the film and a counterfilm they had made and speak in favor of the abolition of the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. So I did. That was my first political involvement. I went around to different church groups, mostly Unitarians.

[A] Actually, it was the campaign to ban the bomb that attracted me to the first political candidate I worked for, H. Stuart Hughes. He was chairman of SANE [National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy] and in 1962 he ran for the Senate in Massachusetts. He was running against Teddy Kennedy, and running against a Kennedy in Massachusetts was like following a death wish. I don't think the Pope could beat Ted Kennedy in Massachusetts. Certainly not John Hancock or Samuel Adams, and I doubt if even the Pope could. But the experience working on that campaign was good; I learned a lot about community organizing, zoning maps, socioeconomic studies, all that stuff you learn in electoral politics. We had a lot of celebrities involved in that campaign, too.

[Q] Playboy: Such as?

[A] Hoffman: I think Steve Allen, and I remember trying to get Marilyn Monroe involved in the campaign.

[Q] Playboy: Why Marilyn Monroe?

[A] Hoffman: I had read a long interview with her in Life magazine and I could see she was really down; lots of love problems, fame problems, problem problems. And, as a psychologist, which is what I was at the time, I looked at that and said, "She's gonna kill herself. She needs a political cause. She needs the Hughes campaign needs her." It was on a Saturday afternoon. I got to her appointment secretary. I remember talking to her: an elderly woman, very protective. And she said Marilyn had gone to sleep and she would bring it up to her Monday and get back to us. That Sunday morning, Marilyn Monroe was dead. Well, I suppose I, along with a couple of million other American males, felt I could have saved Marilyn Monroe; it was probably a universal fantasy at the time. But certainly she and the Hughes campaign would have been an interesting combination.

[Q] Playboy: What was your next project?

[A] Hoffman: Well, although the main issue was nuclear disarmament, that campaign brought in many of the civil-rights organizers who had been working in the South. And gradually, civil rights became the crux of my involvement. I was a field worker for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC. We used to have a joke in SNCC that nobody was a student, that nobody was nonviolent, nothing was coordinated and there was no fucking committee, so it was a good cover. I was also vice-president of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality. I traveled in New England, setting up groups; I went to Mississippi in 1964 and got busted in Jackson.

[Q] Playboy: What for?

[A] Hoffman: Parading without a permit, I believe it was. Three thousand people were busted and kept in a compound. You know, the whites and blacks were so segregated at that time in Mississippi that they actually spoke different languages. I remember you used to walk in some rural areas, black enclaves, and the blacks would come up, want to touch your skin. They were just curious, you know. How did I get that color skin?

[A] I saw Klan meetings in Mississippi with white sheets and flaming crosses; I was arrested in Yazoo City for going through a red light and they didn't have red lights in the town at the time. I sat in a cell in Georgia with a fucking death sentence hanging over my head for passing out leaflets--treason against the state of Georgia. I jumped bail in Mississippi, bail in Georgia; it was just standard procedure. The judge would call you boy, spit in the spittoons, throw you into a cell with a bunch of locals and give them all some liquor and tell them, "This is a civil-rights worker." You got beat up and thrown out. It was an eye opener. In one Mississippi town, they had a laughing barrel. Blacks wanted to laugh in the center of town, they had to stick their heads in the barrel. I remember when they were looking for Goodman, Schwerner and Chaney, the three civil-rights activists who were killed, they were dragging the swamps and came up with five or six bodies, black bodies. Anyway, it was because of all that that we were trying to seat the Freedom Party delegation at Atlantic City in 1964. And it was there that black power became the focal point of SNCC organizing.

[Q] Playboy: Why?

[A] Hoffman: Because our idealism was crushed. We thought we'd won. And then Lyndon Johnson had to make his deal with the Southern Congressmen and he said, Hubert, if you want to come and visit in the White House, I want you to go out and get those fucking niggers off the Boardwalk, you understand, Hubert? A lot of fucking things were twisted, a lot of secret sexual shit was pulled out and used on delegates, a lot of judgeships were dangled. It was the big issue of that convention, but the blacks got shoved into the back of the bus and the regulars got to vote. After that, there was a great rupture within the organization and the black-power philosophy emerged.

[Q] Playboy: What are your feelings on black separatism today?

[A] Hoffman: In any struggle, there has to be a moratorium, where you can isolate yourself and establish a solid base, whether your thing is feminism or counterculture or black nationalism. The blacks are moving along nationalistic lines now. Black power, the Afro haircut, the dashikis, changing your name, being Moslem. I mean, what's Moslemism? It's another religion; it's racist; it's hierarchical, it's feudalistic; what's so good about that? It gets all fucked up. They're going to Africa and the Africans are laughing at them, because they don't wear Afros.

[Q] Playboy: At least one black separatist, Eldridge Cleaver, has returned to the States to proclaim his allegiance to America. Did you know him?

[A] Hoffman: Not really. I met him once and all he had to say was, "Can you get me some amphetamines?" But Anita stayed with him in North Africa when she went over with a group of Yippies. Cleaver started assigning Anita her bedmates. "You'll shack up with this person," he said, and she got furious. "They're crazy, sexist pigs," she told me later, and she's not someone who throws around a word like crazy lightly. She said Eldridge was on a macho power trip; he had bragged about shooting guys who tried to fool around with his wife, Kathleen. He showed people the bloodstains on the walls.

[Q] Playboy: Were you working full time with the movement during that period, or did you have another job?

[A] Hoffman: In '64, '65, I was working as a pharmaceuticals salesman. Sold pimple medicine. Let me tell you, the drug industry in America hasn't changed since the time people were roaming the Far West selling snake-bite medicine out of the back of a covered wagon. I was sitting right in the middle watching all this shit--drugs being sold for three and four dollars a bottle when the ingredient cost something like two cents. It was during that period that I first dropped acid.

[Q] Playboy: Where did you get it?

[A] Hoffman: Aldous Huxley had told me about LSD back in 1957. And I tried to get it in 1959. I stood in line at a clinic in San Francisco, after Herb Caen had run an announcement in his column in the Chronicle that if anybody wanted to take a new experimental drug called LSD-25, he would be paid $150 for his effort. Jesus, that emptied Berkeley! I got up about six in the morning, but I was about 1500th in line, so ... I didn't get it until 1965. The acid was supplied by the United States Army.

[Q] Playboy: The Army turned you on to acid?

[A] Hoffman: My roommate from college was an Army psychologist, based in Maryland. It's been in the news recently that the Army was doing all those experiments with acid in Maryland. The Army has mighty good fucking acid; it was the best I've ever had.

[Q] Playboy: How often have you taken acid--300 or 400 times?

[A] Hoffman: No way. I'd say 100 times, maybe. A hundred times in ten years is ten times a year? I haven't taken it that much, I think. I take drugs less than my friends.

[Q] Playboy: Less than your friend Tim Leary, for instance?

[A] Hoffman: Yeah, poor Tim. Always fucking up, saying things like, "I'm the first god on this planet." I felt that helping him break out of jail was an important revolutionary act; he was unfairly convicted. But when he informed on the people who helped him out, I could have killed him. I'd have beat the living shit out of him.

[A] Anyway, I'm not so pro-LSD these days. I don't recommend it to everybody. Or I advocate people taking it once in their lifetime, period. If I do have an addiction, it's to sex.

[Q] Playboy: Don't acid and sex mix well?

[A] Hoffman: Yes, and so do sex and revolution.

[Q] Playboy: Did your first acid experience have any lasting effect on your life?

[A] Hoffman: It definitely affected my life. After my first trip, I decided I was going to be a full-time activist; at the time, I was a bowling hustler besides working for SNCC. I also decided to get divorced from my first wife, Sheila, leave my cottage with the picket fence, all that. My trip ended, actually, with my giving a civil-rights speech in a church, which some people say was pretty good. Acid just left me with a wild feeling; I talked to God on the phone, long distance. Collect.

[Q] Playboy: God?

[A] Hoffman: God. I've talked to God every time I've taken acid.

[Q] Playboy: What does God say?

[A] Hoffman: I'm not sure God gets to say all that much. It's more, "Ya, ya, right. Who's paying for the call, Me or you?" The Virgin Mary floated down from a cloud and I got horny. It was a lot of fun. The second trip was a bad trip.

[Q] Playboy: In what way?

[A] Hoffman: A minister chased me around. And then a lot of cops came in. There are always a lot of cops coming into my acid trips. In fact, the week before the cocaine bust, I had taken an acid trip in a sexual-experimentation situation--there's a little tidbit for your readers; after all, this interview isn't for Popular Mechanics. I envisioned the entire cocaine bust from beginning to end--police coming in through the windows, the walls, pounding on the doors. I related sex to complications with the police, apparently.

[Q] Playboy: What was the sexual experimentation about?

[A] Hoffman: I knew you'd ask that. At one point in our lives, Anita and I decided to reverse roles. I took care of the baby and she went into the city every day. We wanted to explore the other halves of ourselves, the masculine and feminine halves, and we used sex as a kind of breakthrough. My head is not there now; I think of myself as a monogamous bigamist. I'm still married to Anita, but I'm living with Angel. Everything is a phase, and Anita and I had lots of sexual experimentation with other people during that period. We both tried every kind of sex. The problem with sex for a revolutionary is that it takes up so much fucking time, discussing it and thinking about it. It's all-encompassing. Anyway, we tried it as a learning experience.

[Q] Playboy: Did you learn anything?

[A] Hoffman: Yes, I experienced what I believed to be a female orgasm.

[Q] Playboy: What was it like?

[A] Hoffman: Longer than a male's and like an ocean wave. Male orgasm is like climbing a mountain; when you're at the top, you shoot your jism. The female was more like waves with no real crescendo.

[Q] Playboy: How did you achieve it?

[A] Hoffman: I scrubbed floors, I washed dishes, I had a vasectomy, I had become more or less a househusband and had all the fantasies that go along with that. Anita was off developing her own career, and when she came back and we made love, I was more passive than active. But we've never had a sick relationship, never. In fact, Germaine Greer once said ours was the only marriage worth saving in America.

[Q] Playboy: Why did you decide to have a vasectomy?

[A] Hoffman: I had a doctor cut into my balls as a political act. It was a statement of conscience; it says you're not going to let your sperm scatter through the world, come what may. One reason I got it was because there were a lot of celebrity fuckers--not fucking for the fucking, just fucking to have a drop of the revolution in them--to get pregnant.

[Q] Playboy: They wanted to fuck you in order to have a baby by Abbie Hoffman?

[A] Hoffman: Yeah. When you're playing around, you don't stop and ask, "Did you take your pill today?" And I'm a sexual maniac, if there is such a thing.

[Q] Playboy: When did you lose your virginity?

[A] Hoffman: You're not talking about group jerking off to see if you can fill a milk bottle in a month? We did that once, a bunch of us kids. And we had jerk-off contests to see who could come the quickest.

[Q] Playboy: Did you win?

[A] Hoffman: This does belong in Popular Mechanics. Sure I won; I'm very competitive. Sixteen seconds. But they had to turn their backs. I was shy.

[Q] Playboy: Do you have any particular theories on sex education?

[A] Hoffman: Well, for one thing, I think it's OK to let kids watch their parents fucking. The conventional wisdom that it will scare them, that they'll think their parents are fighting when they're making love, is just way off the wall. We let america crawl around to satisfy his curiosity about sex. Let him do everything, within limits.

[Q] Playboy: Getting back to politics, what changed you from a more or less conventional activist into a radical one?

[A] Hoffman: I have to thank some cops at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1966 for that. Stokely was there, a bunch of SNCC workers, and we were handing out leaflets. Some redneck cops decided to rip our booth apart. They chased us in the dark, pounded the shit out of us, hauled us off to jail. I was pounded into radicalism, beaten into it by the police. That pig was telling me exactly what to do: He told me to get divorced, to drop more acid, to quit work and go to New York and organize 100 hours a day; that's what he told me with the fucking club. So that's what I did.

[Q] Playboy: Weren't you actually on the payroll of the city of New York at one point?

[A] Hoffman: That was later, in the summer of '68. They had that Lindsay policy of putting a couple of activists on the payroll to be a link between the city and the hippies and runaways who were wandering around the streets at the time. Actually, we ended up throwing the money we earned from that job onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. It brought the big board to a halt. People scrambling, fighting for the bucks. Then we got fired.

[Q] Playboy: By then, you'd formed Yippie, the Youth International Party, hadn't you?

[A] Hoffman: Wait. I think I'll take an underground piss.

[Q] Playboy: Now that you're back, why did you decide to form Yippie?

[A] Hoffman: I always added an exclamation point at the end--Yippie!--to express a certain exuberance, joy, optimism. Our main goal was to end the war. As a means, we decided to find a left wing to the hippie movement and use that as a technique to broaden young people's understanding of why they were running away from home, why they were upset with society, why they couldn't smoke marijuana, why they couldn't learn anything interesting in school, why everything was boring, why songs they liked were being (continued on page 218) Playboy Interview(continued from page 80) banned from radio stations, why they were being drafted into an Army when they didn't want to go out and fight. It was a school of the streets, a school of protest and a technique for communicating through the mass media so that people would go to the demonstrations in Chicago, during the 1968 Democratic Convention.

[Q] Playboy: But didn't the Yippie movement become a sort of Frankenstein's monster for you? Didn't the myth become bigger than the reality?

[A] Hoffman: Yeah. I would show up in Seattle and there would be 30 Yippielettes greeting me at the airport with Fuck written on their foreheads. I made a speech in Lincoln Park at the end of the Chicago demonstrations, saying that Yippie was over. It was a technique, not something I wanted as a movement. But the media image was so strong that it stuck. And then the trial brought us back onto the same stage, in a sense.

[Q] Playboy: You've said you were glad you were indicted with the Chicago Seven. Why?

[A] Hoffman: I thought the Government made a serious mistake in giving us a forum through which we could mobilize cross sections of the population, including the A.C.L.U. element, in opposition to the conspiracy law itself. It's still on the books and it's still the most unjust law in the United States. I'm sorry our case didn't knock it out; our conviction was thrown out because we had a loony judge and there were wire taps and all kinds of other reasons.

[A] We were in the perfect setting. Chicago to me was just another Southern town like the ones I had worked in my civil-rights days. This time the enemy became the court system and we wanted to expose its hypocrisies and brutalities. The system radicalizes the person. It happened to me, it happened to Tom Hayden, it happened to everybody. Things pile up and first thing you know, you are being blamed for a police riot.

[Q] Playboy: You participated in every Democratic Convention from 1964 on, didn't you?

[A] Hoffman: Yeah, '64, '68, '72.

[Q] Playboy: What was '72 like?

[A] Hoffman: Let's talk about '76.

[Q] Playboy: Why do you want to skip '72?

[A] Hoffman: I was lost. I didn't know what I was doing.

[Q] Playboy: You expect us to believe that?

[A] Hoffman: I'm always lost. You haven't driven around with me on a dark night. I get lost a lot; I'm an absent-minded fugitive.

[A] In '72, I thought that supporting McGovern was the quickest way of ending the war in Vietnam. Well, the Eagleton affair was an unfortunate accident that showed a lack of idealism; from then on, it was all downhill. McGovern was so bitter, so wiped out by the defeat, and who wouldn't be? He knew things the American public didn't know. He said that dirty tricks were being used, that Nixon's was the most repressive Administration since Hitler's. Some people thought he was a fucking nut. A year later, he was a Jeane Dixon.

[Q] Playboy: Are you going to make it to the 1976 Democratic Convention?

[A] Hoffman: I'll accept a draft. Me and Hubert Humphrey. I met him once in Miami in 1972. He said to me, "You made some good points there in Chicago," and I replied, "You were the point." I also asked him what drugs he liked--he was a druggist, you know.

[Q] Playboy: What do you think of Gerald Ford?

[A] Hoffman: He's a fucking bimbo. All that flashes in my mind is pictures of him falling down and bumping his face. Even in that famous picture of him, where he posed cooking his own breakfast, I don't know if you noticed, but he was marmalading the wrong side of his English muffin.

[Q] Playboy: Do you think he'll be elected?

[A] Hoffman: Sad choice. Reagan certainly has a chance to knock him out. I think it will be Reagan versus Humphrey.

[Q] Playboy: Who do you pick to win?

[A] Hoffman: Humphrey. Tell me again about American democracy, run it down. After 200 years, one of the world's greatest criminals is shooting golf in San Clemente with more estates than the king of France had. And the second-in-command now is the butcher of Attica, Rockefeller. I think the person who wins is the one who gets the most money. It's a buy-in. The United States has the same percentage of millionaires as the Roman senate had. Everybody grew up to be president.

[Q] Playboy: What does the Roman senate have to do with anything?

[A] Hoffman: Just that the people of the Third World are going to be the Visigoths to the Holy U.S. Empire. The fall of Saigon was the end of the American Empire. It lasted 199 years and that's enough. When an empire falls, it's at its most brutal. Almost all the Jews Hitler killed were from 1944 on. They wanted to get rid of the evidence.

[Q] Playboy: We're not sure about the analogy, but let's talk about America's future and your role in it. Assuming you stay underground, what purpose will you be serving?

[A] Hoffman: I want to help create a government that serves the needs of the people, not only in this country but throughout the world. I don't believe change is going to come peacefully in the United States, not without conspiring with anti-imperialist forces abroad. We need a true Communist Party in the United States--one that knows how to reach people. And because of infiltration and harassment, we have to build that party secretly. There's no other choice. American democracy serves those who don't need it. People yell about taxes and about cutting welfare, but 102 billion dollars went to the Pentagon this year. That's more than all the people in South America earn.

[A] So I'm helping to build an underground network in the United States that will last a number of years and will be used in different ways, depending on the political climate. War is built in to this society and as each war comes along, more and more progressive people will resist it. That's why an underground will be needed.

[Q] Playboy: Are you really a Communist, Abbie, or is that just another label to provoke people?

[A] Hoffman: I'm a full-fledged Commie; better Red than dead. I think everybody oughta say they're a Communist. Like my grandmother, she's a great Commie. Anybody who can keep a secret for 50 years is a good Commie. But it ain't no secret anymore; I'm telling. The people who should come out of their closets now are the Communists. If Picasso was a Communist, what is Dave Dellinger? If Vanessa Redgrave is a Communist, what is Jane Fonda? It's here, why hunt for it all over the world?

[Q] Playboy: How about you? How good a Communist are you?

[A] Hoffman: As a Commie, I'm not that good. Like I say, it's my upbringing. I've had a macho, gambler, hustler American upbringing. Nobody's perfect. I'm also white. With blacks you say, Look, there are 16 of you niggers sitting there in a bathtub and there's this guy up on the hill living alone with 16 bathtubs. That's how you organize black Communists. With whites you need psychoanalysis. You say, You want happiness? A worthwhile life?

[Q] Playboy: If you're not great as a Communist, how are you as a revolutionary?

[A] Hoffman: I'm a little queasy about using the word revolutionary about myself, because it has so many implications. I'm a social activist. Most people--especially the intellectual community--call you a revolutionary only when you're dead. A social activist can be alive and, more than that, he can be a personality.

[Q] Playboy: Would the Weather Underground agree with that?

[A] Hoffman: One of my criticisms of the Weather Underground is that it hasn't been personalized enough. It draws its models from abroad--such as the Vietnamese--and downplays the individual in favor of the collective. You can't apply that to America. America is a land of soap operas and the Weather Underground should become a soap opera. The S.L.A. did it, but the S.L.A. wasn't strong enough to withstand the pressure and got sucked into the soap opera itself.

[A] Of course, it's dangerous, putting forth your personality the way I do, because it opens you up to incredible criticism on the part of your comrades on the left. Most of them wouldn't do an interview for Playboy--they'd have to go through all sorts of things, such as, What does it mean and how does one justify it? The Weather Underground has a correct analysis of American history, but it has to broaden it to the masses. The members have to start translating their communications into the American language. They can't speak in a foreign language and they can't speak with foreign experience.

[Q] Playboy: Won't these remarks get you into trouble with other people on the left? Isn't it considered bad form to criticize other radical leaders in public?

[A] Hoffman: It used to be considered bad to criticize movement leaders and, in fact, there was a strong antileader trend. I don't have that view now. I believe there are leaders. I remember Bob Dylan's line, "Don't follow leaders/watch the parkin' meters." Well, that's a pretty fucking dumb thing. You follow a parking meter, you get a bump on the head. It wasn't until recently that I accepted the fact that I was a leader.

[A] Leaders have a responsibility and that's to lead. But being a leader doesn't make you any more important than being a dishwasher. The left will succeed only when it develops more anger for the system than it does for the people who happen to be sitting in the same room. I think that was the major fault with the movement, though I think it's changing now.

[Q] Playboy: How is it changing?

[A] Hoffman: The underground has gone through a faddish phase. There have been movies about it and certainly there's great fascination with Patty Hearst. That should be capitalized on to put forth the political message--and I think it will. They should take advantage of it. I didn't come here with a set dictum that was thought out by my group. I don't have set answers. I answer questions as they come to me, right on the spot, and people can sense that. It makes good reading, it gets the message out, and I think there are other fugitives who are capable of doing it even better than I am.

[Q] Playboy: Perhaps, but one of your chief strengths has always been your ability to use, and often manipulate, the media. Even though you're underground, aren't you still doing that--by doing this interview, for instance?

[A] Hoffman: You know, you have to render unto Caesar when you deal with the press. When I did that show for public television, I viewed myself as the director and controller. In this interview, I don't. But it's a chance I have to take. Someone else will direct this, and it's me who may be used. As far as my being successful, I can't count the number of times I was censored and ended up on the cuttingroom floor.

[Q] Playboy: But still, whether or not you are censored, it draws attention to you.

[A] Hoffman: Sure, it's the Zen technique that's so popular in motorcycle repair shops. You stimulate the opposition to react so that it overpowers itself, becomes its own enemy, and you escape in the process. It's the same technique we used in Chicago during the demonstrations. And it's true that I've studied the technique. You have to learn to communicate. You study your environment--in this case, the electronic jungle of the United States--just the way a Latin-American revolutionary studies the back streets the Buenos Aires or a Vietnamese studies the jungles of Indochina. You learn your terrain and how to use it.

[Q] Playboy: When do you think you've been used by the media?

[A] Hoffman: They tried. When I did that Merv Griffin show--the one where they cut me off the screen for wearing a flag shirt--they got so many complaints they wanted to get off the hook. So they offered me $2000 to sit in the audience a couple of nights later. The idea was that Merv was going to say something and get blipped, then the camera would pan to me in the audience, laughing. They were going to make a joke out of the whole issue. Of course, I rejected that; it would have been co-optation. It's an illustration of repressive tolerance, as Herbert Marcuse described it, which means that America maintains the illusion of freedom of speech. But I wanted to make the point that the Merv Griffin show was an example of electronic fascism--and let it lie there. [A spokesman for Merv Griffin denies that any such offer was made.--Ed.]

[Q] Playboy: So even with the splash you've made in the media, you don't think there's freedom of speech or of the press?

[A] Hoffman: Well, there's that old saying that there's no truly free speech because you don't want someone yelling "Fire!" in a crowded theater. And I always said that free speech is yelling "Theater!" at a crowded fire. But that's one of those things that's fun in college discussions, not in real life. There's an illusion that the press is free because it gives equal time to liberals and conservatives and every once in a while you throw in an extremist for human interest. But the press never really gives you a debate. It's never defined in terms of communism versus capitalism, or of imperialism versus the anticolonial struggle. We watched the Vietnam war for ten years not as the ruling class in America versus the Vietnamese people but as our culture versus the evil force of communism. So it was always loaded. It is still loaded--in Angola, for instance. The madmen who run the Pentagon will do anything to prevent the spread of communism and the media tag along like it was 1964 and the Gulf of Tonkin. The M.P.L.A. in Angola is always referred to as "Soviet-backed." The two other groups are termed "pro-Western" when, in fact, both contain Socialist elements.

[A] The media manipulate everything from start to finish. Take the selection of news: What makes news in America? I turned on the TV set and some guy in Kansas had murdered his family and blown his brains out. Now, I know America makes people crazy. That's the one thing I've learned, going around the country--that people are miserable, unhappy. Why should it be news that someone kills some people? That's to keep the population on edge, anxiety prone. I better not take a risk, I better stay alert, I better stay off the streets, because look how crazy my neighbors are. Why isn't there news that helps people psychically, that builds spirit and optimism instead of cynicism and despair and anxiety?

[Q] Playboy: How about you? Are you anxiety prone, paranoid?

[A] Hoffman: No. But fear is different from paranoia. I have a realistic fear. If I open the wrong door, I'm gonna end up in a cage in Attica.

[Q] Playboy: But suppose there were three FBI agents outside your door and they were pounding on it with rifle butts--what would you do?

[A] Hoffman: Well, you have to be specific with these kinds of questions. First of all, there wouldn't be three. They're like nuns; they come in pairs.

[Q] Playboy: All right, two FBI agents. What would you do?

[A] Hoffman: Hmmmm. Have they eaten?

[Q] Playboy: Come on, seriously, Abbie. They burst in on you--what action do you take?

[A] Hoffman: Well, I think the terms of their release could be negotiated. First thing we do is jump them and tie 'em up in a bag, you know.

[Q] Playboy: You are armed, we presume, for self-defense.

[A] Hoffman: I'm armed. I have two arms ... two feet....

[Q] Playboy: What we're getting at is the possibility of your being taken. Would you rather die than go to jail?

[A] Hoffman: Depends on how much time I'd have to spend there.

[Q] Playboy: How about ten years?

[A] Hoffman: Oh, my God. No, ten is out.

[Q] Playboy: Five years?

[A] Hoffman: You're getting closer. Any chance you could become governor of New York in the next decade or so?

[Q] Playboy: Not likely. If you could choose your way of dying, what would it be?

[A] Hoffman: I used to imagine Richard Nixon losing his temper and strangling me on national television. But I think Eric Sevareid would be a better choice, because he stands for all that's true and rational. If he blew his cool and leaped over his desk to strangle me, everyone in America would find out what I already know--that he's always naked from the waist down. I've been to the CBS studio and seen it. So if I could make him show his pecker and hairy white legs on television while he strangled me--yeah, he'd be much better for the role than Nixon.

[Q] Playboy: Are your fantasies of death different now?

[A] Hoffman: My fantasy today is to die in some sort of struggle, but preferably at the age of 110. Of course, if that door opens just now and it ain't room service....

[Q] Playboy: What would you say to people who claim that because you were driven underground, the Government won and you lost?

[A] Hoffman: To me, the issue has always been defined in terms of hide-and-seek--and I'm on the loose. You know what Ché Guevara said, that he was looking for one person to carry the flag, just one person. And Ché is the saint of Latin America. After the Virgin of Guadalupe, that is--at least it's some virgin. I get my Latin-American virgins mixed up.

[Q] Playboy: And you feel you're that one flag carrier? Aren't you romanticizing this underground life of yours?