Valerie Morse

Against Freedom

The War on Terrorism in Everyday New Zealand Life

1. Welcome to the War on Terrorism

Overseas investment and development re-defined:

3. The First Casualty of War - Privacy

Who is acting on these new powers?

So who are the likely targets for all of this surveillance?

4. The Second Casualty of War - Refugees and Migrants

The case of Mohammed Abbas & Western Union

The case of the Israeli agents

Asylum seekers : the bottom of the pile

The wharfies and the seafarers

The New Zealand government’s relationship with the world

New Zealand aid to the Solomon Islands

Media ownership in New Zealand

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

Valerie Morse

Against Freedom

The War on Terrorism in Everyday New Zealand Life

[Anti-Copyright]

Anti-copyright 2007.

May not be reproduced for purposes of profit.

Published by Rebel Press

P.O. Box 9263

Te Aro

Te Whanganui a Tara (Wellington)

Aotearoa (New Zealand)

Email: info@rebelpress.org.nz

Web: www.rebelpress.org.nz

National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Morse, Valerie.

Against freedom : the war on terrorism in everyday

New Zealand life / Valerie Morse.

ISBN 978-0-473-12236-2

1. State-sponsored terrorism. 2. War on Terrorism, 2001

3. Liberty. 4. Propaganda. 5. New Zealand—Military policy.

I. Title.

327.117—dc 22

Printed on 100% recycled paper.

Cover design: Simi I’Anson-Corrin.

Bound with a hatred for the State infused into every page.

Set in 10.5/13.7pt Adobe Garamond Pro. Titles in Myriad Pro.

Acknowledgments

There are so many people out there who have shaped and continue to shape my thoughts, hopes and dreams for this world. All of my friends in the anarchist community in Wellington have contributed to making this book a reality. In particular, I thank my most thoughtful and generous editor, Torrance, who gave both his time and his not insignficant intellectual abilities to this endeavour. I thank the doctors Ken and Kim whose surgical eyes for detail picked up even the most minute of inconsistencies. My most loving and brilliant friend Simi carved out time to make a striking book cover. I would like to give a special note of thanks to the people in Peace Action Wellington who have provided a space for resistance and education since the start of the war on terrorism. I would like to acknowledge the support of the Freedom Shop anarchist book collective and the Wellington Community Resources Group for their financial support. Finally, I want to thank my family for their unconditional love without which I would have no place to stand.

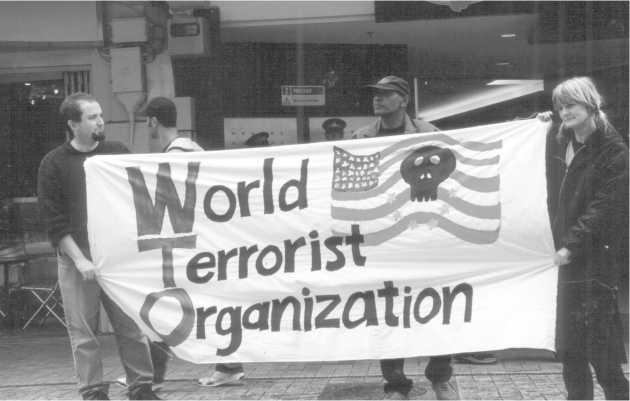

1. Welcome to the War on Terrorism

We are living in a war zone. Every day our freedom, indeed our very survival, is under attack. Since September 11th 2001, when two aeroplanes flew into the World Trade Center in New York City and another into the Pentagon in Washington DC, this war has been openly declared. On the surface, the war on terrorism may appear to be a new phenomenon, marked by extraordinary events. It is not. It is merely the continuation of the same domination and exploitation that has been practised for hundreds of years by those with power against those without — workers, ethnic and religious minorities, people of colour, indigenous people, women, and any other group that challenges this elite power. It is the war of those above against those below. It is the class war; it is the race war; it is a war for power.

In our lifetime, the exercise of continual war has been most notably practised by the United States government. For the generation born after World War II, the perpetual enemy was communism. Like terrorism, communism could manifest anywhere at any time. It was the threat, rather than the reality, which was useful for controlling the domestic population and building a compliant, fearful society. Globally, the enforcement of elite power by the us military was manifested in the bombing of 22 different countries[1] under the guise of fighting communism or the corollary, ‘spreading democracy.’ In the us, the marriage not just of state and corporate power, but of state power and the military-industrial-media complex has created a totalitarian state with all of the appearances of a democracy to its docile, drugged population. In the past 20 years, the accelerated growth of multinational corporations, weapons and communications technology has had the effect of transforming this marriage into a set of interconnected and often incestuous relationships between Western capitalist nation-states and global corporate power.

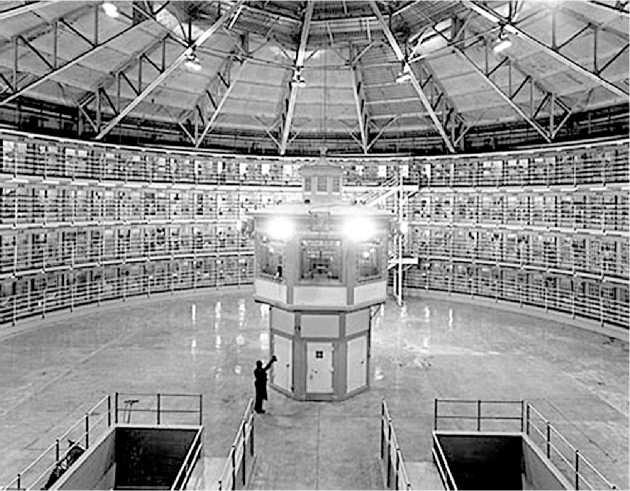

This concentration of power, coupled with modern technology, is one of the most striking ways in which the war on terrorism is markedly different from the war as it has been waged in the past. New technologies of control available to the state and to corporate entities make waging this war easier. These technologies of control include both the subtle and the overt: extensive surveillance over public and private spaces; data collection of nearly every transaction — from telephone calls and banking transactions to dna samples — coupled with the centralisation of that data; the militarisation of police and their use of ever-more deadly crowdcontrol weapons such as tasers; the application of science to developing interrogation techniques and non-detectable torture methods; and finally, the conversion of prison systems to privately-run human warehouses of undesirable people. These are the technologies of the war. The invasion of privacy by the state, the demonisation of refugees and migrants, and the silencing of political dissent, are some of the tactics of the war. The events of 9/11 simply made it easier to apply these technologies and tactics. George Orwell’s dystopian nightmare articulated in his book 1984 should have been a call for action against this intense concentration of power; instead, it has provided a blueprint for oppression.

I do not believe that the war on terrorism is about terrorism. It is about control, and it has both external and internal components. Externally, the war involves the extension of elite and corporate control over natural resources and trade routes, as well as the imposition of a capitalist economy. By extension, it includes the domination of militarily strategic areas around the globe. Throughout us history, corporate and elite interests have coalesced around similar goals to drive foreign policy. These powerful interests — the oil, natural gas, weapons, chemical, pharmaceutical and media sectors — dictate foreign policy and dominate domestic decision-making. In short, their agenda is to maximise exploitation and control while assuming no responsibility beyond the ability to continue these practices. In order that this agenda can be most fully carried out, it is essential that people believe their government is acting on their behalf and for their benefit. This is the internal component of the war on terrorism. In this regard, there are few political tools that are better than war for controlling the domestic population of a nation-state: for uniting people in common cause, for securing consent to abrogate freedoms in exchange for security, for cementing loyalty to the state, and for punishing dissent. The Bush administration needed a war to fulfil the agenda of corporate and elite power. The war on terrorism is not an orchestrated conspiracy: it does not need to be in order to extend state and corporate power. When state and corporate power become inextricably linked, and war is not only central to fulfilling their agenda but actually is one of the goals, it is inevitable that it will be waged.

Capitalism needs war: on one hand, corporate and elite interests can never be satisfied — they can never be too big, too powerful, and too rich — as a result, conflict will ensue as they continually seek to exploit resources and profit from waging war. On the other hand, their theft of global resources and inexcusable exploitation periodically becomes so obscenely obvious to the vast majority of people, who are not content to sit back and get fucked over, that war must be manufactured and manipulated to appear desirable and even necessary for people’s survival. The rich gear up the propaganda machines, create a good enemy and make sure that the people are too distracted by fear and fervour to remember what is actually happening to them. One only needs to look at the history of wars waged by the United States to see this recurring theme: World War I, II, Korea and Vietnam were all wars about elite control, not, as they would have us believe, about ‘fighting fascism’ or ‘fighting communism.’ It is an old saying that “when the rich wage war, it’s the poor who die.” This is truer now than ever.

The war on terrorism emerged from the particular political circumstances in 2001 that required the Bush administration to find a new enemy in order that its corporate sponsors could continue their age-old exploitation of people and planet. The war was not launched as a result of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. In 1993, the World Trade Center had been the target of an attempted bombing, allegedly by al-Qaeda operatives, that put Osama Bin Laden on the us government’s most wanted list. Yet at that time, no war was declared. None was needed by elite power to maintain its position of privilege and carry out its agenda of global exploitation. By 2001, that had changed. Growing resistance to state-imposed economic changes required both a new external military strategy and a new domestic diversionary tactic. For anyone paying attention, the 9/11 attacks were utterly predictable, if somewhat spectacular in their execution. Similarly, the resulting declaration of war was equally predictable.

The end of the cold war signalled a ‘threat deficit,’ as it is known in the war business — the lack of a credible opponent to the us military. In academic and policy circles, there was significant discourse about the downsizing of the us military and its redeployment as a peacekeeping army throughout the 1990s. This sent shivers up the backs of a small group of morally conservative and economically liberal men in power, including Donald Rumsfeld, who would become Bush’s architect of the war on terrorism and the subsequent invasion of Iraq. These men were determined to ensure us military domination of the world, and by extension, the corporate profits of those in the war and oil businesses. For them, the timing of 9/11 was prophetic. By 2001 the effects of the great neo-liberal economic experiment carried out voluntarily in most Western nations in the mid-1980s, and by threat of force in many other places, could now be seen: wealth concentrated in the hands of a very, very few people, massive privatisation of public assets and services, rampant foreign direct investment and widespread currency instability. The tangible reality for many people was sweatshop labour conditions or unemployment; no health care, clean water, food or shelter, massive inflation and a polluted environment. Grassroots resistance had been growing throughout Latin America and the ‘Global South’ for a very long time: resistance to a massive ‘free trade zone of the Americas,’ resistance to further forced economic adjustments dictated by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, and resistance to the destruction of traditional ways in exchange for us consumer culture. When resistance to ‘globalisation’ — the clever new name for the same old hyper-exploitation — came to the us in the late 1990s, the powerful elite understood that it was time for more sustained action if they were to maintain control. They responded by inventing the war on terrorism.

Who are the enemies in this war? Anyone who does not endorse the same world-view as these elites. Who are the allies of the elites in this war? Anyone who can profit from it or who is willing to propagate its message, encourage the loyalty of people to their rulers, instil a fear of the enemy, arm or equip the soldiers, or fight the battles. It does not take much imagination to appreciate why Middle Eastern Muslim men were cast in the role of the stereotypical enemy: they are not ‘us’ — they are not white, they are not Christian, they do not endorse the world-view of Western elite power, they have control of vast oil and natural gas reserves, they live in a strategically important area, and they are sufficiently menacing. They are not the only enemy, of course. They are just the most visible. September 11th delivered them to elite power: a worthy opponent, one who could fly planes into the heart of the us military and bring down the symbols of us capitalism; one that people would rally against, send their sons and daughters to fight and die against.

It was as if September 11th was specifically stage-managed for maximum impact on the psyche of the us people. It is difficult to appreciate the monolithic power of television in daily life, but in the us, where the average person watches nearly five hours of TV every day,[2] it does not imitate life, it is life. The images played over and over and over again cemented the idea of a nation under siege. These images coupled with rhetoric declaring “you are with us or you are with the terrorists”[3] gave the Bush administration free reign to do whatever it wanted — both domestically and throughout the world.

The start of the “war without end” was officially declared by George W Bush on 6 October 2001 when the bombing of Afghanistan began. To most people in the us, the response seemed appropriate, even natural. Drunk on nationalist propaganda, the us population was happy to sanction the bombing of 23 million people in exchange for a false sense of justice done.

It is important to see that the war on terrorism is not the creation of a small number of people who are intentionally manipulating events in a sinister conspiracy to pervert the course of democracy, although certainly some events have been totally manufactured to serve an unseen agenda. Rather, it is that the entire system exists to carry out a fundamentally violent and exploitative agenda while appearing to be in the service of the people. Further to this, the war on terrorism has arisen in a particular way because a broad range of corporate and elite interests with common goals have coalesced with the technologies capable of delivering those things. Internally, the domestic population is subject to ever-greater totalitarian control under the pretence of ‘security.’ Externally, the military invades and occupies to enrich the elite through war-profiteering and in order that they may steal the natural resources of the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa.

It is perhaps easy to see these imperial practices in operation in the us. Where does New Zealand fit in this global war zone? It may seem extreme to call New Zealand a nation-state run by imperial warlords and an elite clique who seek only to consolidate their power and access to resources. I do not believe that it is extreme.

Colonisation, systematic discrimination against Maori, racist immigration policies, support for uk, then us wars, worker oppression, crumbs given to the masses, the illusion of democracy and media complicity, are all part of the history of this war. Like the us, the war on terrorism is nothing new in New Zealand; rather, it is the continuation of the same exploitation practised by those in power for more than 165 years.

New Zealand history is, to be sure, contested ground. What is not contested is that it is a nation-state founded on waves of colonial settlement, primarily British, on-going war with some Maori iwi (tribes), and the establishment of a Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. Given the settlement process established by the 1975 Treaty of Waitangi Act, it is hardly extreme to suggest that there was outrageous theft of land and resources committed by both the Crown and individual colonisers. It is also hardly extreme to suggest that Maori have suffered continual alienation from their lands, culture and language for nearly 200 years. These are not the subject of debate; indeed, the Crown has admitted as much in its apologies to individual iwi, including Kai Tahu, Tainui and Te Arawa. But these are not the incidental by-products of an otherwise kind and generous government trying to do the right thing. They were and are the concerted acts of imperial warlords aiming to systematically control the country. Study the people’s history of the 1860s confiscation of land from Taranaki Maori or the 2004 confiscation of Maori land under the Foreshore and Seabed Act and you will see this imperial agenda in operation. These are but two examples in a long history of exploitation.

The background for staging the current phase of the war on terrorism was set during the fourth Labour government of the mid- 1980s. Its actions on the nuclear-free issue vis-à-vis the neo-liberal economic reforms provide an illuminating example of how the war works: the elite give some small, moral victory to us while stealing on a massive scale. The nuclear-free declaration appeased a large proportion of the political left, coming as it did after a very long, sustained grassroots campaign. This was seen as a major snub to the United States and a strong statement about New Zealand’s independent and principled stand on international relations. But in the Beehive and the boardrooms, the vast resources of the country were being sold off to multinational corporations and enriching a few who were in the know. Moreover, the schism with the us military was more a ruse, a façade, than a reality. New Zealand’s supply of intelligence information from the two spy bases located here continued uninterrupted. Similarly, New Zealand’s military continued to follow the us around the world in its invasions and occupations, albeit quietly.

What in particular marks the war on terrorism as a new, more virulent assault by the powerful against us? That is the subject of this book.

Legal changes post 9/11:

In terms of domestic politics after 9/11, a wave of legal changes followed in the wake of manufactured public hysteria. Both government and opposition party members fully endorsed military action, along with the near-complete abrogation of civil liberties and long established rights in order to support us demands for revenge and control. The history of the initial days after 9/11 and the resulting legislation are the natural starting point for understanding the profound impact that this war has had on everyday life in New Zealand.

The United Nations urged countries to pass legislation regarding terrorist financing following the 9/11 attacks. In New Zealand, the Terrorism Suppression (Bombings and Finance) Act was passed immediately in response to this international effort to cut off the flow of money to terrorist organisations.

This was the first act passed in a suite of legislation aimed at putting strict monitoring and controls over potential terrorism activities. Other legislation followed in rapid succession, including the Crimes Amendment Act (originally the Counter-terrorism Bill), the Border Security Act, the Maritime Security Act and the Telecommunications (Interception Capability) Act. More changes are presently working their way through the parliamentary process, such as a major revision of the Immigration Act and the Aviation Security Bill,.

A strong us directive to the United Nations prompted it to recommend a broad anti-terrorism platform. The New Zealand government chose to copy the us legislation almost verbatim for use in the statutes. This government was not the only copycat. The British, Australian and Canadian governments all passed similar legislation. In all cases, these laws were based on hastily drafted and constitutionally dubious ones such as the USA patriot Act, a catchy acronym that stands for Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act (2001), crafted out of hysterical fear and a desire for control.

The on-going UN-mandated international framework for controlling terrorism has been largely directed by the United States which aggressively ‘persuades’ other countries to adopt legislation similar to that now adopted in New Zealand. When carrots are not persuasive, the stick is at hand. This is certainly the case for many Pacific Island nations, where the tangible needs of the local population must now be ignored so that US-dictated counter-terrorism measures can be implemented.

Chapter one, ‘legislating against terror’ will examine in detail the overall agenda of this so-called counter-terrorism legislation, demonstrating that its net extends far beyond catching terrorists.

The first casualty:

The first casualty of the war agenda was personal privacy. The events of 9/11 were a gift to the security and intelligence community, units that had been long ignored by successive governments. Money was lavished upon the police, Security Intelligence Service and Government Communications Security Bureau while their powers were significantly expanded. With plenty of scaremongering propaganda, all of a sudden it seemed that there was a need to ensure ‘national security’ and identify potential terrorists. The counter-terrorism agenda gained political momentum and public acquiescence.

With bigger budgets came new tools and toys with which to conduct surveillance of the population. The technology of the 21st century allows vast quantities of detailed data to be collected on our daily lives. The targets of this surveillance are largely those on the margins of society — refugees, migrant communities, low-paid workers, political activists, Maori and Muslims. Those who are not mainstream, those whose language, skin colour, religion, history or politics do not fit the mould, are the ‘other’ New Zealand — not white, not middle-class, not content with the status quo. In this war, to be the ‘other’ is to be the enemy.

The targets:

There is a widespread view among many liberal human rights advocates that “what should be a struggle against terrorism [has been turned] into a war on minorities.”[4] But the war on terrorism has never been about terrorism, it is about race and class. It is about who is in charge, in New Zealand and around the world.

Both before and after 9/11, boatloads of desperate refugees fled Afghanistan only to be caught in the anti-terrorist hysteria. The people aboard the ship, MV Tampa, were treated as a threat to the Australian state and deemed politically disposable. As a result, most of them were off-loaded to the desolate pacific island of Nauru. Some who were subsequently invited here received little more consideration; upon arrival, they were placed in long-term detention.

In another instance, Ahmed Zaoui, the democratically elected politician fleeing persecution in Algeria, was greeted by an extended interrogation session with the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. Here was a man escaping a country where the torture and political assassinations of his colleagues were commonplace, only to be imprisoned in solitary confinement in what he imagined to be a fair and just country. An exhaustive inquiry deemed him a legitimate asylum seeker; nevertheless, he continues to be a pawn in an international effort to demonise the entire Muslim world.

His situation can be contrasted with that of two Israeli intelligence agents who were found guilty of fraud for illegally obtaining New Zealand passports. After a slap on the wrist, they were returned home to continue their trade. Those on the ‘right’ side of the war are friends to be treated with due courtesy and the benefit of the doubt.

In any era, to be a refugee, to be an asylum-seeker is to be on the extreme margins of society, highly vulnerable to the whims of state intelligence services and unscrupulous individuals. That vulnerability has increased greatly as the label ‘terrorist’ is unjustifiably affixed and freedom is sacrificed in a ceaseless quest for total security.

Intelligence agents have not limited their search for elusive threats to refugee communities. They have targeted the opponents of government policy who question the legitimacy and the motives of the war agenda. Auckland peace activist Bruce Hubbard, arrested in October 2003 for sending an offensive email to the United States embassy, was just one of many such victims. His sentiments articulated the revulsion felt by many people following the invasion of Iraq in 2003. He served as a useful example to others of the ‘big stick’ wielded by the us government to ensure compliance with their world-view.

Campaigners on a variety of issues, including genetic engineering and ownership of the seabed and foreshore, are also viewed as potential threats to the status quo. A climate of fear generated by the draconian counter-terrorism laws serve to channel our dissent into a narrow range of acceptable protest.

Overseas investment and development re-defined:

‘National security’ became synonymous with the domestic economic agenda behind the war, thereby propelling further trade liberalisation and overseas investment initiatives. The narrow, politically correct range of debate in New Zealand politics meant that no alternative was suggested, let alone entertained. Trade agreements followed in rapid succession. Immediately after 9/11 in the us, Bush urged people to go shopping as a means of fighting terrorism and upholding the ‘American way of life.’ Economic security, defined as the rich getting richer, was equated with personal security from terrorism. Those in charge are simply cashing in on fear, ignorance and well-sown patriotic fervour.

Not content with simply imposing the us war agenda within New Zealand, the Labour government has sought to export the war overseas. Development aid, a largely self-serving exercise most of the time, has been harnessed to fight the war on terrorism. Under the guise of aid, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade has seized upon the war agenda to impose disastrous neo-liberal economic reforms in various Pacific Islands. Out in the Pacific, the naked economic agenda of the war on terrorism is exposed. Local priorities for development are shunted aside in favour of improved security measures. In diplomatic exchanges more reminiscent of Britain’s imperial age, Pacific Island states are told to conform or face severe economic repercussions.

When an opportunity for exploitation becomes evident, the government cloaks imperial intervention in the rhetoric of the anti-terrorism crusade. The 2003 invasion of the Solomon Islands by Australia and New Zealand was nothing but a thinly veiled campaign of conquest.

The deployment of New Zealand’s defence force engineers to Iraq can be viewed as a similarly self-serving act. With development funds and rationalisations, New Zealand soldiers were sent on a mission of mercy — one that was under the control of, and which strengthened the resources of, the occupying us army. There is still a widely held view that New Zealand did not participate in the war in Iraq; it is clear that the Labour party’s media spin-doctoring was frighteningly effective.

The winners and losers:

It is not the soldier nor the average person that reaps any benefits of participation in Bush’s (and Clark’s) war. For the taxpayers this war is an expensive undertaking. Material costs include millions in system upgrades to improve border security, passport controls and surveillance systems, all in the name of countering terrorism. Similarly, the costs of New Zealand troops deployed on 18 different missions in 12 countries are borne by us.[5]

Of course, there are winners in this war. Multinational defence, security, oil, and even dairy interests have a stake in the war. War profiteers are certainly not unique to this conflict. In the modern globalised economic environment, where the average profits of transnational mega-corporations exceed those of small countries, these corporations are in charge.

But do not be misled — the war is not about oil. It is about power. It is about strategic control over the resources that fuel the capitalist system. It is also about constructing and controlling how people see the world. Our consent is manufactured by creating, then dehumanising the enemy, by making the ‘other’ deserving of our wrath. This gruesome reality is cleverly cloaked in evocative nationalistic phrases such as ‘defending our way of life.’

The media:

The complicity of the media is required as part of the ‘hearts and minds’ campaign to win public approval for the war. The local media have been compliant in this respect, but are hardly acting patriotically or altruistically. Rather, the few major media outlets, almost all owned by offshore transnational conglomerates, serve up well-crafted propaganda to the population for their own ends. The uncritical view of New Zealand’s involvement in the war on terrorism must be challenged if any change is going to occur. Without an informed population, we are left to swallow the official line, allowing the powerful to pervert the language and discourse for their own ends.

This war is in its sixth year; the invasion and occupation of both Iraq and Afghanistan have been failures for the local people, who are dying by the thousands and enduring unimaginable deprivation and pain. The continuing bellicosity from within the White House suggests that such failures have not diminished the administration’s blood-lust and penchant for military intervention. The very nature of this war means that it must continue. If there is not an enemy, one will be created. Where, then, will the war take us next?

In terms of military targets, obvious victims are Iran, Syria and North Korea. Certainly, Israeli aggression in Lebanon set the stage brilliantly for a us assault on Iran and/or Syria, both Hezbollah’s patrons. The assault on political, economic, social, and religious spheres of life is likely to continue as this manufactured clash of fundamental- isms[6] becomes more strident. While the preservation of freedom and the extension of democracy are extolled as both the purpose and the goal of this war, they become ever more elusive.

An alternative future:

As an alternative to these malevolent forces, a different conception of security is possible. It is one that requires the engagement of every person in our society. It is a different way of viewing New Zealand and its relationships with the world. In the immediate term, New Zealanders can deal effectively with terrorism by refusing to participate in it. We can take direct action against war, by refusing to serve in a military that fights wars of conquest, by refusing to work for companies that profit from bloodshed, and by creating tolerant and informed communities. As importantly, we must be determined to eliminate the intrinsic hierarchy of governments and nation-states. Fundamentally, these structures exist only to protect the power of the elite over our lives. That is the root of this perpetual violence. We must dismantle domination in our ways of being, every day.

United States vice-president Dick Cheney said that the war on terrorism could last for 50 years or more. This war without end is not a war without victims. Any war, regardless of how it is defined, has casualties. The greatest casualty now is freedom. If we don’t fight for it, we can be sure that George W Bush, Helen Clark and all those with power over our lives will happily sacrifice it for us.

2. Legislating Against Terror

The sensational imagery of September 11th 2001 gives rise to the notion that terrorism, in particular Islamic terrorism, started that day. In fact, the United States has been the staging ground for countless attacks by people seeking to advance one political agenda or another. Over the past 100 years in New Zealand, parliament has been passing laws intended to protect the country against terrorists. Laws such as the International Terrorism (Emergency Powers) Act of 1987 exist to “make better provision to deal with international terrorist emergencies.” This particular law was passed immediately following the 1985 bombing of the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland harbour that resulted in the death of Fernando Pereira.

But it was the scenes of people jumping to their deaths amid burning rubble and the hysterical screams of passengers as flight 77 slammed into the Pentagon that cleared a wide berth for the us government to make harsh new anti-terrorism laws. In the days following September 11th, the United Nations and the New Zealand parliament took steps to respond to the us government’s demand for action.

In a state of shock, politicians from all over the world were anxious to be seen to be doing something to combat terrorism. Beginning with United Nations resolution 1373 — “a comprehensive package of counter-terrorism measures to be taken by member States of the UN”[7] — politicians began to formulate how their own governments could best meet the legally binding obligations dictated by the United Nations Security Council.

Here in New Zealand at the time of the attack the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade select committee had been preparing to pass a law to be called the Terrorism Bombings and Financing Act. Its purpose was to make two of the existing United Nations conventions against terrorism part of New Zealand law.[8] However, in the wake of September 11th, nearly all lawmakers believed it was necessary to tack on a raft of strict new anti-terrorism measures.

On 12 September, parliamentarians from across the political spectrum endorsed a resolution condemning the attacks:

That this House records its sense of outrage at the callous acts of violence that took place in New York City, Washington DC, and Pennsylvania in the early hours of this morning, its distress at the resulting horrific loss of life and injuries, and its condemnation of the systematic acts of savagery; expresses its profound sympathy to the injured and to the families of all those who lost their lives; conveys the sincere sympathy of this Parliament and of the people of New Zealand to the people and the Government of the United States of America, for the distress and loss they are suffering; and expresses New Zealand’s strong resolve to work with all other countries in the international community to stamp out terrorism and swiftly bring terrorists to justice.[9]

From this point forward, members of the House had very different views as to how ending terrorism would best be accomplished. Some of the comments issued in the House that day foreshadowed the particular policy positions that parties have subsequently taken in passing anti-terrorism measures.

For example, act party leader, Richard Prebble, suggested that the flour-bombing of Eden Park during the 1981 Springbok rugby tour was an act of terrorism akin to the September 11th attacks. In keeping with his usual reactionary rhetoric on law and order, Prebble declared, “We will not bow to any terrorists.”[10]

National party defence spokesman Lockwood Smith echoed similar vengeful sentiments, offering whatever support so that “no effort is spared in tracking down the evil bastards who planned this thing.” He then juxtaposed the people who carried out the September 11th attacks with what he called the “anarchists who smash up everything in sight as they oppose trade, trade liberalisation, and globalisation” as two sides of the same coin, opposed to global peace and security.[11]

Green party co-leader Rod Donald, on the other hand, expressed his horror, calling it an “undeclared war,” while cautioning against a knee-jerk response to the attacks. “Even when the perpetrators are identified — and they must be punished — we would urge restraint and insist that a rash and violent response would only increase the loss of life, especially of the innocent.”[12]

Reflecting on what he viewed as the roots of terrorist activity, then Alliance party MP Matt Robson said “One of the outstanding causes of violence is the collapse of good governance.”[13] He was specifically speaking about New Zealand’s development aid to the Pacific. His analogy between Pacific countries and Afghanistan on that day gives a clue to his later support for military intervention not only in Afghanistan but also in the Solomon Islands as part of the on-going war on terrorism.

Foreign Minister Phil Goff evoked images of a coming world war by suggesting that September 11th “will go down as a day of in- famy.”[14] Graham Kelly, head of the Defence select committee, noted the irony in that the House was already in the process of passing anti-terrorism measures. “[W]e should think about what role we can play as a good international citizen and how we can build ... civil societies in those countries that the perpetrators of this evil deed may well have come from . That is not easy. It is a long-term action..."[15]

Given that people labelled as ‘terrorists’ come from all sorts of societies, including the United States, it is difficult to make the connection between the acts of specific individuals and the lack of so- called ‘good governance’ in a particular state. Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh is a good case in point. McVeigh had been in the US Army where he received his training in explosives. His rationale for committing the bombing was too much governance, not the lack of it, on the part of the federal government.

Similarly, New Zealand’s support of the subsequent invasion of Afghanistan under the pretext of capturing those responsible for the September 11th attacks cannot be justified on the grounds that Taleban governance was bad or insufficient. As we ultimately learned, 14 of the 19 people directly involved were from Saudi Arabia.

More chilling was the response from United Future leader Peter Dunne who accepted as natural and obvious that, as a result of the event, “we will be forced to accept changes, limits to our freedom, and limits to live our lives the way we did yesterday, as we seek to remove this cancer from amongst us.”[16]

Against this backdrop the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade select committee sat down to reconsider the Terrorism (Bombings and Financing) Bill. Chairman Kelly related that there was a strong feeling among the members that the bill needed to be strengthened “to take into account the new environment we are in.”[17]

The committee made a decision to use the pending bill, which had already gone through its second reading, as the vehicle to give effect to the United Nations’ demands for more stringent domestic laws on terrorism in the wake of the attacks.[18] In most cases no substantive changes to legislation are made following a second reading, as there is no opportunity for wider comment or input.

The committee hastily addressed the demands in the United Nations resolution 1373 that required countries “to report to it within 90 days of actions they have taken or will take to implement the resolution.” These reports were due by 27 December 2001.

Staff drafted significant and far-reaching amendments to the original bill. Changes encompassed everything from the name, now to be called the Terrorism Suppression Act, to the inclusion of a definition of terrorism and stiff new criminal penalties. All were “intended to cover gaps in New Zealand law.”[19]

Pressured both directly by the us and indirectly though the UN Security Council, members of the select committee felt that urgent action had to be taken. In order to move swiftly most of the members of the committee felt it was appropriate to call for private supplementary submissions on the proposed amendments from a small, handpicked group of stakeholders.[20]

The New Zealand Herald reported that “just eight organisations [were] given the chance to make submissions, and in less than a week.” The organisations were: the Council of Trade Unions, Business NZ, the Law Society, the Law Commission, the Council for Civil Liberties, Amnesty International, the Bankers’ Association and the Institute of Chartered Accountants.[21]

Disturbed by the sweeping powers being included in the amended bill and the abrogation of proper democratic processes, Green MP Keith Locke exposed the secretive hearings to the press in what was labelled a breach of parliamentary privilege.[22] Outraged at the broad changes that were being planned the Auckland and Christchurch Councils for Civil Liberties considered boycotting the submission process, saying that “they should not be stampeded into wartime measures.”[23] Following this furore the select committee opened up the submission process. It rejected Locke’s call for a two-month window, but allowed three weeks, and travelled to Auckland and Christchurch to hear oral submissions.

Meanwhile in the House debate raged as to the proper contribution that the government of New Zealand should make to the newly declared us war on terrorism.

The day after the World Trade Center attacks, Winston Peters questioned the wisdom of allowing the Afghani refugees, rescued by the MV Tampa, to be offered asylum here because he believed that they posed a security risk. In reply Jim Anderton said that it was “intolerable to link someone to suspected terrorists on the basis of his or her nationality.”[24]

Collective punishment is indeed illegal under international law. Yet that is precisely what the government did when it offered the New Zealand Special Air Service (nzsas) to assist the United States in Afghanistan. It linked all 17 million people in Afghanistan with the September 11th hijackers.

The commitment of military troops to the invasion of a country was not without political cost in New Zealand. In an urgent debate and series of questions to the prime minister on 18 September, Helen Clark revealed that a range of possible contributions were on offer, including the special forces. She was not willing to go quite as far as Australia did and invoke the anzus treaty, a motion that was put by the act party. The 1951 anzus treaty is a security agreement between the us, Australia and New Zealand. The proposed motion was peculiar not the least because it was the United States, not New

Zealand, that had abrogated its commitments under this treaty in 1986. At that time, the us Navy would neither confirm nor deny the presence of nuclear weapons or power on board its vessels that were seeking access to New Zealand harbours.

Green party co-leader Jeannette Fitzsimons called upon the government to act only upon a specific United Nations resolution that explicitly authorised the use of force and not to endorse a military invasion by the us. The prime minister did not agree with Fitzsimons instead preferring to follow us directives.

Clark was committed to bolstering the United States military response to the attacks in New York, Washington DC and Pennsylvania. Despite claims by the opposition that Clark was “dithering”[25] in her response, she never hesitated to offer intelligence services and to send military personnel to Afghanistan.

Throughout New Zealand there was an outpouring of sadness and shock at the attacks. There was also an overwhelming consensus that any response must be reasonable and consistent with international law. At an Auckland peace vigil on 17 September, local activist Jen Margaret urged that we “keep in mind that two wrongs don’t make a right.... The best hope for a de-escalation of this sort of terrorism is to try and understand the possible reasons why it is happening.”[26] In Wellington thousands of people converged on the streets at lunchtime on 20 September in a rally hastily arranged by two concerned mothers from Island Bay.

Operation Enduring Freedom was launched on 7 October 2001. This attack on the people of Afghanistan was ostensibly incited by the us desire to capture Osama bin Laden. Yet, there is evidence that suggests that bin Laden’s extradition to Pakistan to stand trial had been negotiated at the end of September. us ambassador to Pakistan Wendy Chamberlain was aware of the deal.[27] For whatever reasons, the immediate capture and prosecution of bin Laden on criminal charges did not suit Washington’s interests. The bombings began.

A debate in the House on 3 October reinforced the New Zealand commitment to the war, both overt and covert. The Labour party and the Alliance both endorsed sending the nzsas, justifying the deployment under Section 51 of the United Nations charter.[28] Jenny Shipley and Richard Prebble, staunch loyalists to the United States, moved stronger motions supporting military action. Wyatt Creech said that not supporting a military response was equivalent to doing nothing about terrorism.

Foreign affairs minister Phil Goff’s comments, however, revealed that the greatest contribution that New Zealand would make would not be the troops on the ground, but rather the intelligence information supplied by the Waihopai intercept facility near Blenheim. Uncle Sam has subsequently recognised this useful contribution to the war on terrorism in a Congressional report.[29]

While Clark shielded her decision to send troops under the cover of the United Nations, the government refused to support an amendment that would have limited the nature of their support by proclaiming that the response was “in accordance with international law, with the objective of apprehending terrorists and bringing them to trial, not for revenge or retaliation.”[30] Does this mean that Labour was happy to sanction a military invasion that was not in accordance with international law or was carried out for revenge?

The Alliance supported the amendment, which subsequently failed. Nevertheless, when the debate closed, the Alliance in concert with all of the other parties voted to send nzsas troops to Afghanistan. Only the seven Green party MPs voted against military intervention.

This decision resulted in the great fracturing of the Alliance party. By 25 October the leader of the party, Jim Anderton, was desperately trying to defend his support for the war to party members who were deeply uncomfortable about it.[31] West Auckland members passed four strong resolutions at their October meeting, the most critical of these being that their members of parliament withdraw support for the motion passed on 3 October.[32] While this demand was watered down at the annual conference a month later, it required all members to review their support for the war.

The turmoil within the Alliance over the war on terrorism was matched by turmoil in the Defence, Foreign Affairs and Trade select committee that was considering the Terrorism Suppression Bill. The Committee received 143 submissions on the Bill — a striking contrast to the original, to which no submissions had been made.[33] This level of response reveals the concern about many of the provisions in the draft, particularly given the short time frame for responses.

There was unanimous concern about the denial of basic human rights and freedoms in the draft legislation. A huge range of New Zealand society commented on the legislation, both individually and through such organisations as the New Zealand Society of Authors, Greenpeace, the Institute of Chartered Accountants, the Council for International Development, the Council of Trade Unions and the Privacy Commissioner.

The criticisms of the legislation questioned the necessity for the law — full stop — and the process being used to enact it. Particularly contentious areas of the proposed bill included the definition of terrorism, the process of designating people or organisations as terrorists, the judicial processes and the use of classified information that could not be made public.

Auckland University professor Jane Kelsey’s submission was critical of Mr Goff’s plan to speed the legislation, noting that it “raised serious questions of constitutional propriety ... and the bypassing of proper democratic process.”[34] Several Auckland anarchists made the point more bluntly by proclaiming “the New York incident of September 11 seems to have had the effect of leaving governments blind to democracy..”[35] The New Zealand Council for Civil Liberties submission says “We are at a loss as to why this legislation needs such a massive amendment, which is clearly ill considered, and potentially draconian and possibly unworkable. Resolution 1373 and 1368 do not require it.”[36]

A survivor of Nazism noted in her submission that “great emphasis is given to the word ‘law’ [but] nowhere is mentioned that the government of the day makes those laws themselves.”[37]

Of uniform concern to all of the submitters was the definition of terrorism proposed in the original bill. The United Nations had not been able to agree on a definition of terrorism and none was included in the two resolutions relating to the attacks of September 11th.

Greenpeace offered the most comprehensive overview of the difficulty inherent in any definition of terrorism. Their submission canvassed some of the generally accepted definitions and made three critiques of the proposed New Zealand definition. Neither violence nor violent crimes were central to the definition, by including intent it became a very broad and ambiguous term, and the proposed list of crimes might, under some circumstances, catch non-terrorist ac- tivity.[38]

In the initial bill even protests and civil disobedience could be defined as terrorist activity. “I can’t see how international terrorist groups can be combated by limiting free speech, dissent and peaceful protests ... Surely democracy and dissent go together like bacon and eggs,” wrote one person.[39] Along the same lines, Aucklander David Parker noted that “it is a huge mistake to imagine that the holding of certain ideas make a crime somehow worse than it already is.. The fundamentalists will have won a huge victory if we too create categories of Thought Crime — we must resist that at all costs.”[40]

The process by which individuals or organisations were designated as ‘terrorists’ also received widespread criticism. The process gives exclusive power to the prime minister in consultation with the attorney general to decide who is or is not a terrorist. Thus it is a political process rather than a judicial process and is potentially open to corruption by a prime minister “without the morals, scruples and sense of responsibility.”[41] Most salient is the point that “matters of innocence and guilt are usually established by the courts in this country.”[42]

Submitters to the bill from all backgrounds expressed their concerns that support for liberation struggles such as that against the apartheid regime in South Africa, those by the Irish Republicans and by the Tamil Tigers would result in a ‘terrorist’ designation. Similarly, acts of solidarity with such groups or indeed legitimate worker struggles within New Zealand could also be classed as terrorism.

The use of classified information to make a designation, along with the provisions for a review by the court system, were two of the other areas that were widely criticised in the submissions. One submitter believed that “governance of the country was being handed over to the international intelligence network and foreign agencies, including the cia and Mossad through this law.”[43] Crucially, New Zealand’s lack of guaranteed access to the intelligence information that the United Nations was using to designate terrorists, along with the requirement that it be accepted without questions, would leave the government in an information vacuum.

The privacy commissioner had objected strongly to the use of classified information by security agencies in an earlier law, the Immigration Amendment Act 1998, noting that it was becoming a trend to value security more highly than “cherished and long established rights.” He restated these concerns more strongly in his submission and criticised the new powers extended to the police as one of the agencies with the ability to use such information. “This is a matter of concern in terms of transparency and accountability. Great care should be taken before according the New Zealand police the status of secret police.”[44]

The provision allowing the use of classified evidence in the designation process means that once designated, the terrorist designation can only be challenged on a point of law, not on the evidence presented. If the evidence was accepted, the prime minister could designate a person as a ‘terrorist,’ the person had no right to see the evidence (or even a summary of it) and could not challenge that designation other than on procedural matters.

On 22 March the select committee reported back to parliament on the proposed legislation. Its report contained many changes, amendments that would satisfy some of the critics of the bill. But, for many, it remained a dangerous step towards totalitarianism.

Mr Locke lodged a minority report on the bill. It could have been called a dissenting opinion as it continued to challenge the fundamental necessity for what he described as a draconian law. He used a debate on 24 April to point out that the definition of terrorist was still so broad “as to catch many otherwise legitimate activities of New Zealanders” and that due process through the court system was still effectively being denied.[45] Nevertheless the committee report paved the way for its eventual passage on 8 October 2002. Aside from the Greens it had full parliamentary support.

Less than a week later a bomb ripped through a nightclub in Kuta, Bali, killing nearly 200 people, including three New Zealanders. Coming little more than a year after the 9/11 attacks, and very close to home this devastating blow in a popular New Zealand holiday spot made many members of parliament more anxious to legislate against terror.

The government had already signalled that the Terrorism Suppression Act would be complemented with other terrorism-related laws. On the eve of the long Christmas holiday, the government introduced the Counter-Terrorism Bill. It is not uncommon to have a push on the last day of the year to tidy-up loose ends, pass controversial bills and introduce new ones. That was certainly the case on 17 December 2002.

Setting the stage for the coming year, Phil Goff indicated that the nzsas might well go back to Afghanistan. Locke asked if the United States would use nuclear weapons to attack Iraq and act mp Ken Shirley called for an urgent debate on a suspected terrorist who had been detained by the New Zealand Immigration Service. The request for this debate was denied because the speaker of the house Jonathan Hunt did not believe “that the detention of one possibly illegal immigrant needs to be the subject of an urgent debate.”[46]

The person detained was Ahmed Zaoui, whose case was soon to explode across the headlines amid allegations that the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (nzsis) lost crucial evidence, and suspicion that the inspector-general of Security Intelligence was openly biased. The Christmas holiday would come and go while Zaoui sat in solitary confinement in Paremoremo prison.

Throughout the world the dawn of New Year 2003 was filled not with joy and hope but with apprehension and anxiety about the seemingly inevitable war in Iraq. The United States administration was absolutely unmoved by rational evidence and domestic and international political pressure. The Bush administration was busily fabricating evidence of weapons of mass destruction, and manufacturing propaganda linking Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein to the 9/11 attacks to justify its case for the invasion.

Here, while Clark criticised Bush, she committed New Zealand assistance to efforts in Iraq following the war. Like our other traditional Western partners — Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom — the government wanted to stay on the right side of the us. New Zealand has always strongly supported the United Nations. Given us arrogance towards the United Nations and its failure to acquire a Security Council endorsement to provide adequate political cover from the potential fallout, Clark would not risk making a commitment of troops to the initial invasion. However, Clark’s government was supporting us campaigns, albeit less obviously and with better public relations than the Australians were. The frigate Te Kaha had been deployed to the Gulf of Oman and air force Orions had been sent to assist in surveillance missions. Clark went to great pains to manufacture a strict delineation between the mission in Afghanistan and the mission in Iraq. The separation of these two missions was not made by the Bush administration. Without a doubt, New Zealand forces were freeing up the us military to do other things.

Media hysteria that portrayed Saddam Hussein as an evil villain with direct connections to the September 11th attacks created fertile ground for the acceptance of additional counter-terrorism measures in the us. These measures included military on the streets of major cities, armed air marshals on commercial airliners and the passage of the usa patriot Act which effected draconian anti-terrorism measures and gave a free hand to the federal police and security agencies, including the cia and fbi.

Some of these additional measures were imported into New Zealand in the form of the Counter Terrorism Bill. It was referred to the Defence, Foreign Affairs and Trade select committee on 1 April — just ten days after the start of the war. Under the guise of ratifying additional United Nations conventions specifically against plastic explosives and nuclear materials, its intention was to create a new area of law relating specifically to terrorism.

The committee received 25 submissions on the bill. Most were highly critical of the inclusion of non-terrorist offences within a law about terrorism. The committee heard from Professor Matthew Palmer, dean of the Victoria University school of law, who eloquently argued that terrorism is no different from other criminal behaviour except in its motivation. He noted that while motivation was an element to consider when sentencing a person, it should not be the basis for a new area of law.[47]

There were several major areas around which criticisms of the bill revolved. These included interception warrants, computer assistance orders and tracking devices. Almost without exception all submissions on these sections of the bill believed that civil liberties and privacy were being seriously compromised.

The clauses allowing intercept warrants were largely seen to give police broad powers to go fishing for evidence of crime. As the bill did not mention anything specifically related to terrorism, it could be used for any offence.

Similarly, forcing people to assist police in accessing computer data represented “a significant extension to existing police powers and a departure from established common law and statutory rights.” A person would effectively either be denied the right to avoid selfincrimination or be charged with an offence for exercising the right to remain silent.[48]

The Crown Law Office affirmed that some of the provisions were prima facie inconsistent with the New Zealand Bill of Rights. Crown counsel advised that the ability to track people directly “constitutes an intrusion on reasonable expectations of privacy..”[49] That particular official, however, believed that the value of this measure in combating terrorism justified this intrusion.

Computer programmer Stephen Blackheath of Lower Hutt prepared a cogent submission detailing precisely why this legislation was dangerous to democracy, in that it went far beyond its stated aim of deterring terrorism and, rather, greatly increased state power. He likened this gradual, but discernible, erosion of freedoms as a move towards a totalitarian state and invited the committee to carefully consider its motives in passing such a law.[50]

A more distressing expression of concern was sent to all of the members of the select committee after the formal submission process had closed. A senior doctor employed by the New Zealand police emailed a letter in which he said, “I am now examining my conscience to decide whether I can continue working for the police. As a private citizen, I am terrified at the potential for abuse of this power. I am devastated by the threat it poses to the property and privacy of individual law-abiding New Zealanders.... This law-to-be represents a huge step towards the establishment of a police state.”[51]

The debate on the Counter Terrorism Bill did not go off without a hitch. On 21 October, under urgency, the House considered splitting off many facets of the bill into separate laws. After a long night of charged debate during the second reading, curious bedfellows emerged.

In a rare marriage of ideological opponents, Stephen Franks said, “I rise for the ACT party to take the unusual step of supporting Mr Keith Locke’s warnings.” Clause 7, bringing changes to the 1961 Crimes Act, created concern for both parties. Specifically, the penalty of seven-years’ jail for merely threatening to do harm or causing significant disruption to a commercial activity or a civil administration was unduly harsh and left the law open to interpretation.

Franks argued with National mf Wayne Mapp, rightly pointing out that many things could be captured by the definition of “causing risk to one or more people” — including the promotion of smoking. “This provision does not have an exception for proper purpose, or good faith or political debate” he concluded.[52]

Therefore you will not find the Counter Terrorism Act in the annual Statutes of New Zealand but its provisions are still there. The bill was split into amendments to six existing laws including the Misuse of Drugs Act, the Crimes Act, the Terrorism Suppression Act, the Security Intelligence Service Act, the Sentencing Act and the Summary Proceedings Act.

Deaf to the demands of the submitters and the New Zealand public at large, the government had more anti-terrorism legislation underway before the Counter Terrorism Bill emerged from the select committee.

The Maritime Security Bill and the Border Security Bill were introduced in 2003 and were quickly and conveniently referred to the Government Administration select committee. This committee has largely dealt with financial reviews of various government bodies and miscellaneous legislation that does not fit easily into the ambit of another select committee. It is difficult to understand why these two bills, with obvious connections to national security and international trade, were not referred to the Defence, Foreign Affairs and Trade select committee. Both laws were motivated by a desire to meet United States requirements in the wake of September 11th.

The committee’s report back to parliament on the Maritime Security Bill indicated that significant issues covering international security, trade and treaties were canvassed in this proposed legislation. New requirements under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea and the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code had been pushed through by the US shortly after 9/11. Those provisions dealt with search and seizure powers, international container shipping, identification systems at ports and designation of security areas.

The Government Administration committee noted the difficulty of not actually defining the word security in the law. The committee members placed that difficulty in the too-hard basket and proclaimed that the meaning of security was implicit. The word security has been defined in New Zealand law three times but those were considered inappropriate in this context. Thus the committee avoided its responsibility as law makers and left it open to later judicial interpretation.

Furthermore, the committee was comfortable in making it legal to violate the New Zealand Bill of Rights when dealing with a security incident. The report states that “we believe that the constraints imposed are necessary.”[53] These lawmakers are willing to err on the side of violating fundamental freedoms in order to provide security that they cannot define.

This was not the end of the terrorism agenda. Subsequently, the Telecommunications Interception Capability Bill (2002) was introduced. It requires that telephone and internet companies help in snooping on citizens. The major companies, Telecom and Clear, had only one concern: the cost of compliance. The question of privacy and civil liberties issues were hardly touched upon in the submissions to the select committee. All of the companies were supportive of the intention of the law.

In the process few voices of dissent were heard. The National Council of Women suggested that perhaps the protection of privacy was under threat. The Anti-Bases Campaign, a grassroots group working to end us listening posts in New Zealand, argued that the wording of the legislation did little to protect the privacy of a person whose emails or phone calls might inadvertently be caught up in an interception warrant. Nevertheless, no changes to protect privacy were included.

The Labour government then introduced the Identity (Citizenship and Travel Documents) Bill. The provisions of this bill include vast new powers for politicians. The minister of Internal Affairs is granted powers to refuse to issue, or to cancel, a New Zealand travel document on the grounds of national security. The minister can also apply to the High Court, when it is sentencing a person for a terrorism related offence, to forbid the issue of a passport.

In April 2006, the Immigration Department began the process of reviewing the 1987 Immigration Act with a view towards making significant changes. Without a doubt, the review is being driven by the agenda of the war on terrorism and numerous aspects are cause for serious concern. The use of classified information, the storage and use of biometric information about applicants, the extension of powers to detain people, and the removal of all but one right of appeal, all signal the government’s intention to restrict not only immigration but the ability of people to seek asylum here.

This web of new legislation is the framework of the agenda against freedom. It is a highly structured and well thought out plan to extend state power further into every New Zealander’s daily life, to erode our privacy and our freedom.

The world of international terrorism may seem very far from our daily life. However, its effects are very real.

3. The First Casualty of War - Privacy

While the events of 9/11 were changing the entire political landscape in New Zealand almost overnight, bubbling beneath the surface were the longstanding agendas of intelligence agencies that would now become a centrepiece in the government’s response to terrorism. The agendas were simple: larger budgets, greater emphasis on security issues in Cabinet and increased powers. The nzsis and police had patiently waited for an opening that would positively shift the government’s attention to them. September 11th provided them with that opportunity. The first casualty of this war became our privacy.

Supporters of the war on terrorism argue that greater state powers to invade personal privacy are not only necessary but are a common good to protect everyone’s freedom.[54] This linking of increasingly repressive and invasive state force with ideas of freedom is one of the most alarming tactics of the war. Similarly, the notion that surveillance technology is politically neutral, natural and inevitable is a potent myth propagated by those in power who are intent on retaining it.

New technology, when used to watch, listen and record both personal events and public spaces, makes surveillance almost undetectable. The events of September 11th provided an opportunity for quickly manifested new laws to further erode of individual privacy. This chapter outlines the moves towards greater state surveillance: which agencies are charged with conducting that surveillance, the tools they are using to do it, and who uses the ‘intelligence’ they gather.

A great majority of people in New Zealand are under the impression that we have a right to a certain degree of privacy. What happens to that right when the country is at war? Does privacy enjoy some particular boundaries that cannot be breeched even in wartime? To what extent will the New Zealand government use the ruse that they are keeping us ‘safe from terrorists’ in order to further invade our privacy? Certainly in the aftermath of September 11th the New Zealand government said it needed to have far greater access to the intimate details of our lives in order to avert a terrorist attack. “PostSeptember 11 and ‘the Bali tragedy’ there was an understanding by politicians of the importance of security issues,” said one director of a New Zealand intelligence agency.[55]

Under New Zealand law you do have a right to privacy. The Privacy Act of 1992 theoretically places limits on the government’s right to collect and keep information about you. The fourth of the Privacy principles provides assurances that personal information collected by an agency shall not be collected by unlawful means.[56]

Privacy is certainly not absolute in Western liberal countries, however. The argument for the invasion of privacy by the state is that in order for it to operate effectively it must know something about the people that it serves. If you accept that argument then the extent of the invasion of your privacy is merely a matter of negotiation. An alternative notion is that governments actually collect information not in order that they may better serve their citizens, but rather that they may better control them. The stealthy movement towards total surveillance by state agencies certainly lends credence to this idea. Regardless of how you conceptualise the role of the state vis-à-vis personal privacy, the ramifications of data collection are the same: the state has vast stores of information about all of us.

Despite this, most of us are not terribly worried about a few of our details being recorded in a computer database. We willingly sign up for Fly-buy points, we complete entry forms at the grocery store for free prizes and pass our credit card numbers over the phone to the pizza takeaway. The state collects information about us every day, including the amount of our pay cheques, our health histories — after a visit to the emergency room or a cervical smear — and our car registrations, just to name a few.

Are there limits to this data collection? How much information does the government hold about you and what can they do with it? Who gets to decide?

Under the guise of improved security prompted by 9/11, privacy is being eroded in increasingly dramatic ways through new counterterrorism laws, greater police and intelligence powers and advances in surveillance technologies. Together, these laws, powers and technologies form an impressive arsenal for the counter-terrorism initiative the government wages in the name of so-called ‘security.’

The agenda of this part in the anti-terrorism campaign includes the further extension of the state into your private life. Why? Put simply, if the government knows its citizens intimately — by collecting statistics about the whole population and about individual citizens — it has greater power to control them. Knowledge is power.

The tension between personal privacy and the state’s desire for information is ancient. The data collection technology, however, is relatively recent. Fingerprints, id cards, data matching and other privacy invasion schemes were originally used on populations with little political power, such as welfare recipients, immigrants, criminals and members of the military. Subsequently it was applied to groups higher up the socioeconomic ladder. Once in place, the practices are difficult to remove and inevitably expand into more general use.[57]

With little public debate or understanding, two laws were passed in late 2003 and early 2004 that significantly changed the parameters of state involvement in your life. The first of these was the Crimes Amendment Act (No. 6) along with Supplementary Order Paper 85 (sop 85). The second was the Telecommunications (Interception Capability) Act.

Prior to 9/11, security and intelligence issues in New Zealand were very far down the political agenda. A restructuring of the defence force eliminated air combat capability that was deemed extraneous. The emphasis was shifted to participation in international peacekeeping efforts and protection of the country’s exclusive economic zone that extends more than 300 kilometres off the coast. The physical isolation of the country meant the government was far more engaged in hyperactive trade negotiations at the behest of multinational corporations and in dampening the demands of its citizens for decent healthcare, free education, and sustainable welfare than on fighting global terrorism. As a result, the arrival of the Crimes Amendment Act (No. 6) and the subsequent sop 85 to the parliamentary select committee stage had taken years. Given the events of 9/11 and the subsequent expansion of electronic communication, the timing seemed prophetic.

The media labelled this amendment to the Crimes Act as an antihacking law — in effect, a law intended to stop the unauthorised access of communications. The implications for the security and intelligence community could have been significantly limiting. However, the sop provided a specific exemption for intelligence agencies including the nzsis, the Government Communications Security Bureau (gcsb) and ‘law enforcement agencies,’ such as the police.[58]

The Act also amended the definitions of ‘private communication’ to extend it to e-mail, faxes and pagers, not just oral communication as had previously been the case. The term ‘listening device’ was changed to ‘interception device’ and the definition of ‘intercept’ was broadened to recognise the range of technology that might be used to facilitate an interception of a private communication.

It is worth noting that the Law and Order select committee reported that it was current nzsis policy to comply with Privacy principle 9, e.g. that government agencies were not to keep information longer than necessary for the purpose it was collected. The wording of this report suggests that nzsis picks and chooses which of the Privacy principles it wishes to comply with and when it wishes to do so.

It is peculiar that the select committee did not view this Act as an expansion of surveillance powers since the privacy commissioner had warned more than five years earlier that greater transparency in the nzsis process of obtaining an interception warrant was essential to protecting the rights of New Zealanders.[59] This Act was a useful tool to consolidate the power of the intelligence community, as it provided greater clarity on how far they could legally violate your privacy.

The passage of the Telecommunications (Interception Capability) Act then further smoothed the way for the government to access electronic information by removing technical barriers that could impede their ability to hack into your computer system. Internet Service Providers (isps) — those companies that provide you with dial-up or broadband access to the internet and email — were saddled with a ‘duty to assist’ in the legal execution of a search warrant, including providing encryption keys.

The Law and Order select committee report emphatically stated that the “bill does not change or extend in any way the existing powers of surveillance agencies to intercept communications.”[60] This statement was either naïve or intentionally misleading. New telecommunications technology has, of course, fundamentally changed the way that we communicate. As one researcher noted, “the potential to intercept all of someone’s electronic data in 2003 is a much, much larger intrusion into somebody’s life than it was to intercept all of somebody’s electronic data and communications 25 years ago.”[61] In other words, the data available from modern communications technology has the potential to provide far more than just the content of your communications. It can pinpoint your location and the location of the recipient, for example. The law provided a technical means for amassing detailed surveillance without the necessity for broadening the legal right to do so.

Who is acting on these new powers?

There are four agencies that are primarily concerned with the operational side of intelligence and information gathering. These are the gcsb, the nzsis, Defence Force Intelligence and Security (dfis) and the newly created Police Strategic Intelligence Unit (siu). These agencies form the core of the security-intelligence complex, each covering a different aspect or sphere of information.

For years the nzsis, gcsb and defence forces have been at the bottom of budget priority lists for both National- and Labour-led governments. The splendid isolation of the country in geographical terms means a traditional attack or invasion is extremely unlikely.

Like their counterparts overseas, security agencies have struggled to find a role in the post-cold war era. In the early 1990s defence and intelligence experts actually predicted a downsizing of the us military as the red menace of communism faded into history. Threatened with obsolescence, these agencies seized upon the war on terrorism with fervour because it provided an excellent new purpose. Not only would this war provide a fresh reason to exist — and require an injection of money — it would continue to do so, as the threat of terrorism was continually redefined as the ‘war without end.’

Revitalised by the threat of a new enemy, the security and police forces have sought to strengthen their traditional spheres of operation. The first of these agencies is perhaps the least known. The gcsb focuses on signals and communications intelligence. Since 9/11, the gcsb has grown to a staff of 303. In 2005 it received a substantial budget increase from $30 to $38 million.

The existence of this highly secretive agency was completely unknown to the New Zealand public, and Prime Minister Muldoon had little idea of its true function when it was established in 1977. It took the courage of several agents within the organisation and the work of researcher, Nicky Hager, to reveal the agency’s work to the world in a book called Secret Power. It was here that the existence of the five-member spy-network ukusa — that includes not only the United Kingdom and the United States but also Canada, Australia and New Zealand — was exposed and the echelon network data- gathering methods revealed.