Abbie Hoffman and Jonathan Silvers

An Election Held Hostage

“Reagan Had Informants at the CIA, the NSC, Even Inside the White House Situation Room”

“The obscure we see eventually. The completely apparent takes a little longer.” —Edward R. Murrow

An investigation of the 1980 reagan campaign’s clandestine operations provokes the following questions:

-

Did the Reagan team make its first arms-for-hostages swap five years before the contra deal?

-

Did George Bush’s CIA contacts help sabotage president carter’s hostage negotiations?

-

Were the Tehran captives jailed for an extra 76 days to tip the 1980 election toward Reagan?

On January 20, 1981, minutes into his first term. President Ronald Reagan performed a diplomatic miracle.

For more than a year, a revolutionary government in Iran had held 52 Americans hostage in retaliation lor America’s support of the deposed shah. Id the world’s dismay; President Jimmy Carter was unable to secure their release. Traditional methods of persuasion—an admixture of pleas, threats, economic and military sanctions—proved useless against a fanatic regime that preferred martyrdom to capitulation. Armed with little but epithets and chibs, an Iranian mob had crippled the (barter Presidency and brought America to its knees.

And there the nation remained until Reagan placed his hand on a Bible and took a solemn oath. Hall a world away, the fanatics who had once chanted “Death to the Great Satan” instantly scrambled to appease the country’s new leader. Barely two hours q after the Inauguration, ‘with thanks to Almighty God,” Reagan made the announcement that America had been longing to hear for 444 days: “Some 30 minutes ago. the planes bearing our prisoners left Iranian airspace and they are now free of Iran.”

In the jubilation of homecoming, no one asked why the hostages had been released al that paititular moment. No explanation seemed necessary. Throughout his Presidential campaign, Reagan had slammed the Iranians as “murderous barbarians” and implied that, if elected, there were ways of handling such people. “We did not wish to inherit the hostage crisis,” explains Richard Allen, a Reagan campaign strategist and his first National Security Advisor. “We wanted to make it clear to the Iranians that this was the one issue Reagan was unstable about.” The Reagan transition team circulated menacing rumors that military reprisals and Nonnandylike invasions were “under consideration.” (According to Allen, its propaganda was not without humor: “What’s flat and glows in the dark?” “Tehran, five minutes after Reagans Inauguration.”)

It would be five years before Reagan’s antiterrorist posturing came under scrutiny. In November 1986, a Lebanese newsweekly reported that National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane had secretly negotiated an arms for hostages deal with the Iranian Revolutionary Council in an attempt to win release of captives taken during Reagan's first term. As the scandal unfolded, it was discovered that this was not the rash enterprise of a small group of National Security Council adventurers but a rigorously conceived Presidential initiative.

The White House quickly shifted into damage-control mode. Attorney General Edwin Meese promised a “complete and impartial investigation”—just after the most incriminating documents were shredded. Through a series of discreet tactical maneuvers, the Administration managed to confine all official investigations of Iran/Con/m activities to 1985 and 1986, the period in which the White House said the initiative had begun. The Government panels were deterred from exploring the conspiracy’s origins.

The While House tried despciately to conceal earlier activities for a simple reason: I he Reagan Administration had approved and encouraged the sale of U.S. arms to Iran not only in 1985 but four years earlier, in 1981. Ammunition, replacement parts, even sophisticated American weapons systems began to flow into Tehran—via Israel—within two months of Reagan's 1981 Inauguration.

Moreover, a commanding body of evidence and testimony has recently surfaced that suggests that members of the 1980 Reagan-Bush campaign secretly pursued openings to Iran as early as September 1980, two months before the election. On at least two occasions, emissaries of Ayatollah Khomeini met with Reagan advisors. The Iranians allegedly offered to detain the American hostages past Election Day, humiliating Carter anti ensuring a Reagan victory Given the speed with which the Reagan Administration approved arms sales to Khomeini, the testimony of several Iranian dignitaries and the fact that a similar arms-for-hostages pad was made later, there is every reason to suspect the Reagan campaign capable of cutting a deal.

Former President Jimmy Carter has voiced doubts about his opponent's integrity in that race. In response to our question regarding his knowledge of these allegations. Carter wrote the following on February 24, 1988:

We have had reports since late summer 1980 about Reagan campaign officials dealing with Iranians concerning delayed release of the American hostages. I chose to ignore the reports. Later, as you know, former Iranian president Bani-Sadr has given several interviews stating that such an agreement was made involving Bud McFarlane, George Bush and jxuhaps Bill Casey. By this lime, the elections were over and the results could not be changed. I have never tried to obtain any evidence about these allegations but have trusted that investigations and historical records would someday let the truth be known.

This letter prompted an investigation, the results of which follow.

The Campaign

In retrospect, it seems surprising that President Carter was able to mount a serious bid for re-election in 1980. 1 he United States was suffering from the rapid erosion of its industrial base, an Arab oil embargo and post-Vietnam war trauma. Added to double-digit inflation and rising unemployment, the Iran hostage crisis came to symbolize the country's general deterioration. Whether Caner was a victim of those circumstances or their chief architect is debatable. but much of the public regarded him as a poor manager of the complex American system. An internal campaign memo written by Carter’s chief pollster, Patrick Caddell, put it succinctly: “By and large, the American people do not like Jimmy Carter. Indeed, a large segment could be said to loathe the President.”

Loathe him they might, but pit him against the Republican nominee. Ronald Reagan, and lo! Carter suddenly had a decent shot at re-election. Whatever faults Carter had. Reagan matched them one for one. Reagan’s appeal was limited; he was seen as hawkish, misinformed, ultraconservative, too Hollywood.

At its core, the eleclion was a race to select the lesser of two evils. Voters couldn't decide whether they wanted helplessness or extreme conservatism. Time-magazine preference polls consistently showed the candidates separated at most by two percentage points. In mid-October. Tune gave Carter a slight edge, 42 percent to Reagan’s 41 percent.

William Casey. Reagan’s campaign manager, found these statistics unnerving. Above all else, he feared that in the last weeks before the election, Carter would pull an “October Surprise”; that is, bring the hostages home, win back the public’s confidence—and send Reagan back to the ranch. Richard Wirthlin. Reagan’s chief pollster, estimated that a pre-election hostage release could earn Carter five to ten percent of the undecided vole, more than enough to ensure his re-election. Without a hostage release, however. Wirthlin figured that a Reagan win was certain.

Casey had not come so far to Ik denied victory at the 11th hour. At his insistence, the Reagan-Bush campaign began to defend against the possibility of a pre-election hostage release.

Campaign Counter-Intelligence

In early September 1980. Casey and .Meese put together an intelligence operation called the October Sui pi ise group, consisting of ten strategists dedicated lo monitoring inner While House maneuvers. Ils ranks included Richard Allen. Dr. Fred Ik Ie. later Undersecretary of Defense, and John Lehman, later Secretary of the Navy. The New York Times called their activities “war-gaming.” “the guessing of possible Carter moves and the formulation of countermoves.’’ But they soon went beyond guesswork. Like any intelligence operation worth its cloaks and daggers, the group went alter information at its source—the While House and environs.

And they got it. In Cassopolis. Indi ana, on October 28. 1980. then Congressman David Stockman boasled that he had used a “pilfered copy” of Carter’s briefing book to coach Reagan for a televised debate. “Apparently, the Reagan camp's ‘pilfered goods' were correct,” reported The Elkhart Truth “Several limes, both candidates said almost word for word what Stockman predicted.’’

It wasn't until three years later, after the debate incident was recounted by Laurence I. Barrett in with History and Jody Powell suggested that a serious breach of ethics may have occurred, that Congress launched a full-scale inquiry into the affair, dubbed Debalegate. The Subconi in it lee on Human Resources, chaired by Democratic Representative Don Albosta of Michigan, spent nearly a year reviewing internal Reagan-cainpaign operations. Its definitive report. “Unauthorized Transfers of Nonpublic Information During the 1980 Presidential Election,” was released in May 1984. It shocked the few who read its 2400 pages. What had begun as a routine inquiry into the alleged theft of a debate briefing book exploded into a damning indictment of a campaign stall that employed unethical—if not illegal—tactics whenever convenient. The subcommittee didn’t mince words: “As the documents and witness statements show, Reagan-Bush campaign officials both sought and acquired lionpublic Government and Carter-Mondale information and materials.”

The subcommittee’s greatest wrath was reserved for the October Surprise group. William Casey had constructed a vast surveillance network that collected internal White House data. Richard /Mien estimates that perhaps 120 foreign-policy and national-security consultants were affiliated with the Reagan campaign; many had military or intelligence backgrounds. (In comparison, the Government’s National Security Council employs only 65 foreign-policy professionals.)

U.S. district court judge Harold Greene, reviewing a motion for a Special Prosecutor, had only criticism for “an information-gathering apparatus employed by a Presidential campaign that uses former agents of the FBI and the CIA.” The Justice Deparimcni, run by Reagan appointees, saw no need for a Special Prosecutor.

The complex October Surprise apparatus was admirably stalled and structured. Al Meese’s urging. Admiral Robert Garrick, a retired naval-reserve officer, created a network of loyalists—retired, reserve and active-duty Servicemen—at military bases around the country. 1 hey were instructed to report any aircraft movements that might be related to the hostage situation. It proved effective. For example. Brigadier General Johnny Grant, of the California National Guard, apparently telephoned Admiral Garrick with news of aircraft maneuvers near “where the spare parts are,” implying that the Carter Administration was preparing to exchange military aid for the hostages.

Allen. Ikle and Lehman monitored While House policy decisions for the camp. “We had two firm and enduring rules,” Allen said recently. “Do not interfere with the hostage situation. Deal with no classified information.”

Allen apparently had difficulty enforcing those guidelines. The Albosta subcommittee discovered that by October 1980, senior Reagan advisors had informants at the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the NSC, even inside the White House Situation Room. Moreover, those informants had security clearances ranging from “Confidential’’ to “Eyes Only.” Several NSC', staff members later testified that they had “close friendships” with Reagan aides.

Those friendships often resulted in the sharing of confidential documents. Four-star generals gave the Reagan camp details of the Stealth bomber project. Secretary of State Ed Muskie’s agenda for SALT 11 talks landed on Meese’s desk. Allen received staff reports intended solely for National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski. “These documents were sometimes extraordinarily sensitive material of the highest nature,” Brzezinski told The Washington Post.

The Reagan team was not above paying for information. The informant who allegedly delivered Caner’s debate papers to Casey was paid $2860. ostensibly for research papers that he apparently never prepared.

While those bits and pieces were undoubtedly useful to the Reagan campaign, its primary concern was getting data on the hostages. Here, loo, the quality and quantity of ils espionage was exceptional Between official Stale Department briefings, leaks and their purchases. Reagan advisors may have known as much about the crisis as the President, “ lop Secret—Eyes Only” and “Secret/Sensitive” documents from the U.S. embassy in Tehran were found in Ronald Reagan’s personal campaign file. Reagan said he didn't know how they got there. Angelo Codevilla, a Senate Intelligence Committee staff member, probably passed to Reagan headquarters details on the hostages’ whereabouts in lehran. One entry in Allen’s telephone log reads. “13 Ociobei 1980. 1151 Angelo Codevilla—938-9702. DIA—Hostages—all back in compound last week. Admin, embargoed intelligence. Confirmed” Allen could not offer an explanation. though the message—written in his handwriting—is hardly cryptic. Another Allen memo dated October 10, 1980 (“F.C.l.—Partial release of hostages for parts”), suggests that the Reagan campaign knew the White House was evaluating an arms swap with the Iranians. (EC.L are the initials of Fred C. Ikle.)

Many of Reagan’s best moles were motivated less by devotion to the Republicans than by animus toward Carter. That was especially true of those in the intelligence agencies. Shortly alter the shah was deposed. Carter chewed out the CIA lor misinterpreting the unrest in han. He chastised the Director of Central Intelligence. Admiral Stansfield limier. and reorganized or fired much of the Middle East division. Not surprisingly, relations between the While House and the CIA grew increasingly hostile. “There was no doubt that the CIA was more Republican and didn't like the Democrats,” says Admiral Turner. “And I'm certain that many hoped a Republican would return to the While House.”

CIA operations virtually collapsed in ('alters last year. “The Carter Administration had made a serious mistake,” noted Charlie Beckwith, the colonel in charge of the Desert One rescue team. “A lol of the old whores—guys with lots of street sense and experience—left the agency.”

Another CIA asset volunteers, “Sian Turner fired the best IHA operatives over the hostage crisis. The firees agreed among themselves that they would remain in touch with one another and with their contacts and continue to operate more or less as independents.”

Casey courted those malcontents with considerable success. For example. General Richard Ellis, then head of the Strategic Air Command, put his services at Reagan’s disposal. One memo to Meese noted, “Due to his rank and position, [General Ellis] cannot formally institute a meeting, but if a meeting were requested by R.R., he would be happy to sit down with him.... [The general] wants to blow Jimmy Carter out of the water.” Reagan later appointed Ellis to the U. S. - S o v i e t Standing Consultative Commission.

Reagan’s selection of George Bush as running mate also proved serendipitous. Bush had served as Gerald Ford’s Director of Central Intelligence, an appointment he once called “the best job in Washington.” Although his tenure lasted less than a year, he maintained informal ties to the agency after he left and staffed his ill-fated Presidential campaign with former CIA officials. When the Bush and Reagan campaigns merged in July 1980, their intelligence-gathering abilities increased substantially. Many CIA veterans close to Bush, notably former (TA Director of Security Robert Gambino, assisted Casey and Allen in campaign activities.

“Bush certainly had the ability—and the connections—to get the campaign into the intelligence communities,’’ says Turner.

Prescott Bush, the Vice-Presidential candidates brother, courted a consultant to the U.S. Iran Hostage Task Force named Herbert Cohen In a September 2, 1980, letter to James Baker (George Bush’s campaign manager and now Secretary of the Treasury), Prescott Bush said he expected that Cohen would provide the campaign with “some hoi information on the hostages.” Cohen eventually sent Casey four confidential NSC reports.

By the fall of 1980, the Carter While House was riddled with moles, spies and informers. But preoccupied by the continuing crises and the campaign, the President’s advisors remained ignorant of the dirty tricks being played by the Reagan-Bush team. “We were aware that we had made enemies,” says Jody Powell, “but we didn’t think they were inside, chipping away at our foundation.” Given the sensitivity of the stolen documents and the impunity with which the moles acted, the President’s defenses, like those at the embassy in Tehran, were pitifully inadequate.

Back Channels

In desperation over the Iranians’ ref usal to deal with the United Stales on the diplomatic level, the Carter While House looked to unofficial channels as a means to resolve the crisis.

In February 1980, Dr. Cyrus Hashemi, a former Iranian CIA operative turned arms dealer, made the Administration an offer. Claiming to be a cousin of Hashemi Rafsanjani, one of Khomeini’s lieutenants and later speaker of the Majles (Iran’s parliament), Dr. Hashemi said he had contacted Khomeini's advisors and found them willing to revive negotiations. If the President wished, he would gladly open back channels. There was, of course, a catch: The Iranians would free the prisoners only in exchange for U.S. offensive weapons.

A word about arms: After the 1953 CIA-sponsored coup that installed Reza Pahlavi as shah. Iran depended on the U.S. for nearly all its military hardware and training. In 1978, shortly before he was deposed, the shah paid U.S. defense contractors more than $300,000,000 for arms and spare pans. After the Islamic revolution, however, the While House embargoed all military shipments to Iran, and the shah’s purchases were never delivered. Without U.S. ammunition and spare parts, the ayatollah’s American-equipped military was approaching paralysis.

When Hashemi suggested that Iran might be willing to bargain, there was reason to think the proposal legitimate. “We felt an outsider would have a better chance of getting to Khomeini,” says a State Department official. “We were quite willing to consider anything. A weapons package didn’t seem unreasonable, especially since it had been paid for.” Dr. Hashemi was referred to State Department officials, but after several weeks of discussion, his services were declined.

The fact that a covert arms trade was even seriously considered by the Administration sent dangerous signals io the munitions underworld. “Iranian arms merchants were coining out of the woodwork,” says Gary Sick, principal White House aide for Iran. “Each one insisted that he alone had a direct line to Khomeini They were mostly opportunists, some really disreputable characters, out for honor and profit.”

Houshang Lavi probably came closest to circumventing Presidential authority. A naturalized American born in Iran, Lavi acquired an intimate knowledge of Iranian internal politics by brokering various arms deals the arranged the sale of F-14 aircraft to the shah in the inid-Sevencies). In December 1978, he participated in a covert (TA mission that removed high-tech Phoenix missiles from Tehran when the shah's days were numbered.

Lavi was infuriated by the hostages' prolonged captivity and was certain that it could have been avoided. Alter the disastrous Eagle Claw helicopter rescue attempt in April 1980, it was obvious to him that Carter would never appease the ayatollah, so he took the initiative. As Lavi pul it at our meeting on Long Island. “/ attempted to free the hostages.”

In the spring of 1980, Lavi approached Mitchell Rogovin, a lawyer with the John Anderson Presidential campaign, with an unusual offer. “Lavi said Iranian president Bani-Sadr had authorized him to pursue hostage negotiations,” says Rogovin. Lavi sketched out an arms-for-hostages plan similar to the one Hashemi had ottered the Department of State eight months earlier. Lavi made one demand: If they succeeded, “credit must not go to Carter.”

“He was adamant about that,” says Rogovin. “He wanted it known that Carter’s abilities were severely limited.”

Lavi’s offer scared the Anderson campaign. “It involve the candidate in negotiations regarding the hostages . . . was too dicey to contemplate,” wrote Alton Frye, Andersons director of policy planning. But rather than risk losing an opening to Tehran, the Anderson campaign referred Lavi to the Stale Department.

The White House had no doubt that Lavi could deliver F-M parts to 'Tehran; whether he could gel the hostages out was another story. “An arms swap, legitimate as it may have been, was tantamount to paying ransom to terrorists,” says a Carter aide. ‘Too risky, loo unreliable. Carter had some real problems with it.” In the end, the While House ignored all outside otters and settled in for the long haul.

Sabotaged Negotiaions

In September 1980, Carter’s patience was rewarded. Sadegh labatabai, Khomeini’s influential relative, contacted Washington with an urgent proposition. Iran would free the hostages if the U.S. released Tran’s financial assets, refrained from intervention in Iranian affairs, and returned the shah’s properly, including the military supplies that had been paid for.

After months of silence, Iran was understandably eager to resume talks. The Iran-Iraq war, which began in late September 1980, had inflicted heavy casualties on the Iranian army. The black market could provide only a fraction of the supplies Iran needed. Khomeini grudgingly acknowledged his dependence on Satan America.

The While House recognized that il would have to deliver some arms and spare parts to Iran as pari of an over-all settlement. “We suggested [to the Iranians] that we would make $150,000,000 worth of military equipment available to them after the hostages were released.” states White House aide Gary Sick. “In fact, we held a lot more, as much as S300.000.000. But there were many offensive weapons and classified materials we didn’t want to get back to Iran.” Carter reluctantly approved an arms package that omitted all offensive weapons and lethal aid.

Reagan advisors panicked when they learned that Carter was close to a deal. In an October 15th memo marked sensitive and confidential, Allen informed Reagan, Meese and Casey that an “unimpeachable source” had warned him of an impending hostage settlement: “The last week of October is the likely time for the hostages to be released. . . . This could come at any moment, as a bolt out of the blue.”

(Allen says that his source was reporter John Wallach, who Allen believes learned confidential details of the negotiations from Secretary of Stale Edmund Muskie.)

Reagan loyalists then made several attempts at undermining Carter. On October 15, 1980, WLS-TV, the Chicago ABC affiliate, announced that the President was about to approve an arms-for-hostages exchange and that live Navy planes loaded with offensive weapons were prepared for a flight to Tehran to consummate the deal. Not a word was true. Larry Moore, who broke the story, allegedly got his misinformation from a highly placed member of the U.S. Intelligence community who was linked to the Reagan campaign. Soon after, columnist George Will, a Reagan booster, remarked that a fleet of transports loaded with arms was bound for Khomeini’s army. On October 17, The Washington Post got closer to the truth when it reported that a spares-for-hostages deal was an element of the hostage settlement.

The public outcry over those planted stories was enormous. Carter was accused of dishonoring America, of caving in to terrorist blackmail. As if that weren’t enough, the Iran negotiations began to founder. Iwo weeks before the election, labatabai suddenly became inscrutable. He delayed, changed terms at random and, mysteriously, abandoned demands for arms. He also reneged on a promise to have the hostages home by Election Day.

There is no doubt that in the last weeks of the campaign, Reagan-Bush campaign members successfully undermined Carter’s diplomatic efforts. Their espionage, for the most part, was confined to Washington power circles. But they also attempted to deal directly with the Iranians.

In September 1980, Allen got a call from Robert McFarlane, then an authority on Iran for the Senate Armed Services Committee. McFarlane told Allen that he knew a representative of the Iranian government who might be useful. “McFarlane wanted us to meet him; he was emphatic.” recalls Allen. “And against my belter judgment, I agreed.” Allen asked another campaign advisor, Laurence Silberman, to accompany him.

The four met in the lobby of L’Enfant Plaza Hotel in Washington. The Iranian envoy informed them that he was on good terms with Khomeini s inner circle. “Then he spun a web about how he could gel the hostages released directly to our campaign before the election,” recalls Silberman. “And al that point, we cut him off. Neither Allen nor I had any interest in his proposal. 1 told him flat-out that we have only one President al a lime and that all deals regarding the hostages would have to go through official channels.” After 20 minutes, Allen and Silberman thanked the Iranian envoy for his concern and left. End of story. If you take them at their word, everyone behaved with what Silberman called “scrupulous propriety.” Maybe. In the interest of national security, the Reagan team certainly could have reported this overture to the White House, as the Anderson campaign had honorably done with Houshang Lavi.

Among other things, the paucity of details makes the account disturbing. The lime and date of the conference, even the envoy’s identity, are all unknown. Allen remembers him as an oddball, a ’Hake,” an Iranian living in Egypt; Silberman thinks he might have been North African (McFarlane has yet to return our calls.) But considering the enormity of the envoys proposal, and Allen's own well-documented obsession with Iranian affairs, that particular blackout seems too convenient.

Three highly respected professionals, whose livelihoods depend on recalling names, faces and events, unaccountably develop amnesia, h’s unlikely that they would meet an envoy without knowing beforehand his status, reliability and objective. McFarlane would presumably have used every facility al his disposal to make sure the contact was legitimate. If he had had any reservations, it’s doubtful that he would have been so insistent. And if McFarlane’s judgment was so poor—if the envoy was a “flake”—it’s even more doubtful that he would have been welcomed into the next Administration.

But while Allen, McFarlane and Silberman were claiming to reject the deal in Washington, their colleagues were scanning the globe for similar openings to Iran. P.L.O. representative Bassam Abu Sharif, Yasir Arafat’s chief spokesman, told journalist Morgan Strong that a Reagan backer had approached PL.O. headquarters. “During the first campaign, the Reagan people contacted me,” claims Abu Sharif. “One of Reagan’s closest friends and a major financial contributor to the campaign. ... He kept referring to him as Ronnie... He said he wanted the RL.O. to use its influence to delay the release of the American hostages from the embassy in lehran until after the election. . . . They asked that 1 contact the chairman [Arafat] and make the request. . . . We were told that if the hostages were held, the PL.O. would be given recognition as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people and the White House door would be open for us.”

The P.L.O. was a reasonable choice to serve as hostage broker. Iwo weeks after the embassy take-over, Arafat negotiated the release of 13 Americans. If Arafat could persuade Khomeini to release some hostages, he might just as easily persuade him to hold the rest a little longer.

The PL.O. has so far refused to document those charges. “We have the proof if it is denied.” says Abu Sharif. “And they said they would deny it if it ever became public. 1 hope it does, because I would like to drop the bombshell on them.” Still, we have no corroborating details to confirm the account.

Its clear, though, that Reagan advisors look foolish risks. Barbara Honegger, a former policy analyst in the Reagan White House, is certain that al least one of their initiatives paid off. In late October 1980. while she was working al the Reagan campaign headquarters in Arlington, Virginia. an excited staff member boasted, “We don’t have to worry about an October Surprise. Dick cut a deal.” Her colleague, she suggests, was referring to Richard Allen, and the deal involved the American hostages in Tehran.

The Tragedy Of Bam-sadr

Among the casualties of the hostage crisis were the two presidents of the adversary countries, Jimmy Carter and Abolhassan Bani-Sadr. Although separated by vast political and cultural differences, their personal philosophies were surprisingly similar. Like Carter, Bani-Sadr advocated human rights, the democratic values of the Islamic revolution and stability in the Middle East. Both worked feverishly to end the hostage standoff. And both were ousted by the same despot.

Carter limped home to Plains. Bani-Sadr, too often on the losing side of a three-year power struggle that saw many of his colleagues executed, fled Iran in the night. After six weeks in hiding, he surfaced in July 1981, when France offered political asylum on the condition that he give up politics. He has spent the past seven years quietly brooding over the political situation in his country.

When the Iran/Con/ra scandal broke in November 1986, Bani-Sadr began making startling accusations. T he Reagan arms-for-hostages scenario, he claimed, was not a recent inspiration; Reagan had made an arms deal with Iran months before he was first elected. From the wilderness of exile, his charges rarely made it to America. And even when they did, he was portrayed as a bad loser and his charges were dismissed.

Then, in the fall of 1987. two things happened: Allen admitted to having met an Iranian envoy on behalf of the Reagan-Bush camp, and Israel was discovered to have sold Iran American-made military supplies in 1981. Bani-Sadr s claims took on disturbing credibility.

In April 1988, we were invited to France to interview the exiled president. When we arrived, the French government was embroiled in a scandal eerily similar to the one we were investigating. Prime Minister Jacques Chirac had secretly paid Iranian terrorist groups close to $30,000,000 in ransom for three hostages, purchasing an “April Surprise” to advance his battle against President Francois Mitterand in the upcoming election. The French electorate was not swayed.

Bani-Sadr first learned that the ayatollah was considering a secret deal with the Reagan-Bush campaign in late September 1980. Hashemi Rafsanjani, one of Khomeini’s key advisors, was sending a secret emissary to the United Slates to assess the political situation and try to arrange a more lucrative settlement than the one the While House was offering him. It was that emissary, Bani-Sadr claims, who contacted McFarlane and later met Allen and Silberman in Washington.

Rather than reject the envoy, as Allen and Silberman claim, Bani-Sadr insists that Reagan’s campaign advisors embraced his basic plan. Before returning to Iran, the envoy had other meetings with senior Reagan advisors. “They agreed in principle that the hostages would be liberated after the election,” says Bani-Sadr, “and that, if elected, Reagan would provide significantly more arms than Carter was offering.

“For Khomeini, working with Reagan was preferable for several reasons,” he says. “Reagan represented the working capital of the United Slates—he had close lies to the banks, the financial community—so trade would be easier. With Reagan President, Khomeini could also tell his people that he had destroyed two enemies of the revolution: the shah and the man who harbored the shah, Jimmy Carter.”

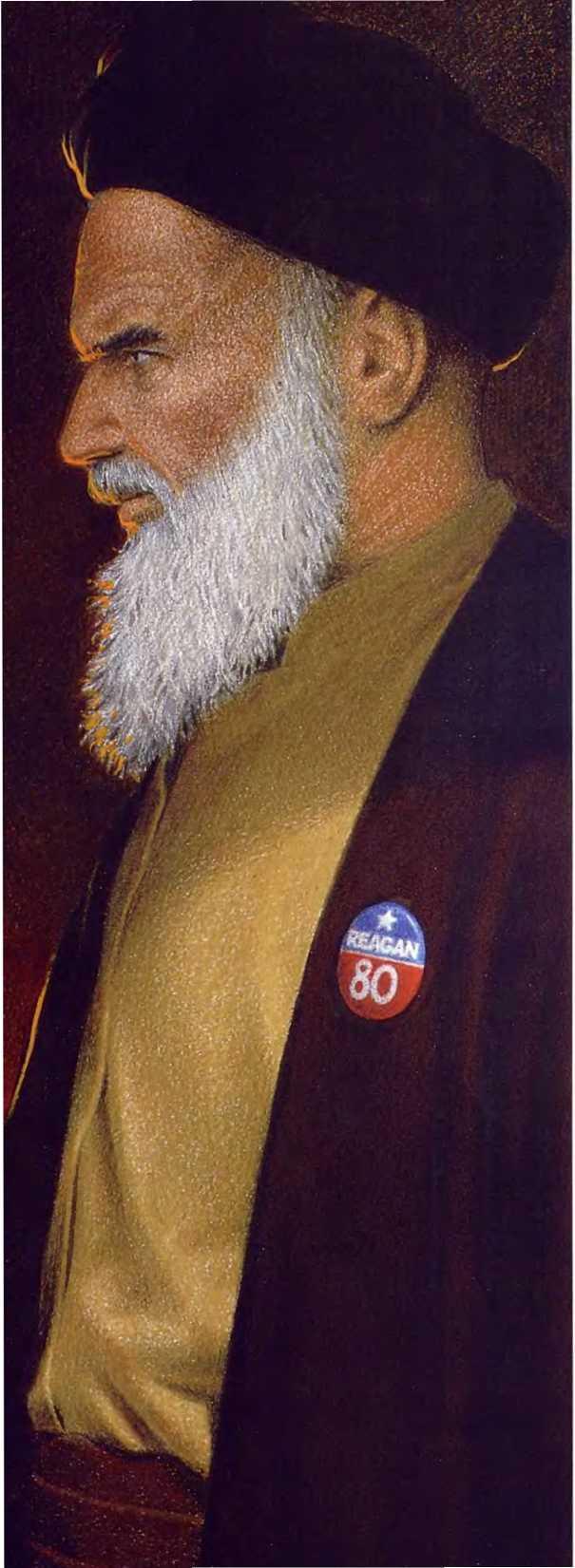

Bani-Sadr maintains that with the election drawing near, the Reagan-Bush team was eager to finalize a deal. At some point during the last two weeks of October, with the election days away a final meeting was held in Paris, al the Hotel Raphael. “There were three factions present,” he claims. “Representatives of the Reagan campaign, representatives of the ayatollah—Mohammed Beheshti [head of the radical group Hezbollah] and Rafsanjani—and independent arms merchants. 1 have confirmed several of the names: Dr. Cyrus Hashemi. Man tic her Ghor-banifar and Albert Hakim.”

Representing the Reagan-Bush campaign, says Bani-Sadr, was none other than George Bush.

That last detail struck us as implausible. It would have been extremely difficult lor a Vice-Presidential candidate to sneak off to Paris in the last weeks of a f renetic campaign for a clandestine meeting. Bani-Sadr appreciated our skepticism. He insisted, however, that his intelligence was accurate and that by late October, negotiations had reached a serious stage that required a commitment f rom the highest level of the Reagan-Bush campaign.

(Al our request. Kirslin Taylor, the Vice-President’s Deputy Press Secretary, reconstructed Bush’s schedule for October 1980. With the exception of a few rest days and Sundays, there are no extended gaps in his itinerary. Theoretically, however, a roundtrip journey to Paris could have been accomplished within a days time.)

In exchange for keeping the hostages until Inauguration Day, the Americans pledged that Iran would receive U.S. military supplies. Representatives of the Reagan campaign assured the Iranians that “third parties—independent arms merchants, friendly foreign governments— would handle delivery of specific parts and weapons,” says Bani-Sadr.

Bani-Sadr concedes that much of his intelligence comes second-hand. “As president, I knew that a deal was under consideration, but I was unaware that it had been consummated until after the arms arrived.” He didn’t learn more details until a year after he was exiled. Friends and loyalists within the Iranian military began sending him photocopies of secret Islamic Revolutionary Parly documents, several of which are said to describe the hostage deal. Throughout our interview, he consulted official-looking papers written in Farsi. “These documents are extremely sensitive,” he says. “I don’t want them circulated. It would seriously endanger my sources. II a Congressional investigator came here, 1 would take the risk and give him copies.”

Mansur Farhang, a former UN ambassador from Iran, also believes that some arrangement was made with the Reagan camp. “Khomeini did not make distinctions among American politicians,” says Farhang. “He regarded them all as dan gerous. But in October [1980], I noticed an abrupt change in his attitude. He became accommodating, very relaxed about the prospect of a Reagan Presidency.”

Farhang regards Bani-Sadr’s intelligence as sound but fragmentary. “Bani-Sadr puts the bits and pieces together himself and constructs something that he regards as the truth,” he cautions. Still, many elements of Bani-Sadr s story have been corroborated.

Mansur Rafizadeh, a former SAVAK chief and CIA asset, insists that a Paris meeting took place in mid-October. as Bani-Sadr described. Representing the Reagan-Bush campaign were Donald Gregg, a former CIA official (later Bushs National Security Advisor), and an authority on Iran who served as a translator. Rafizadeh has also stated that elements within the CIA endorsed Reagan-Bush coven efforts: “Some CIA agents [in Iran] were briefed by agency officers to persuade Khomeini not to release his prisoners until Reagan was sworn in. . . . The CIA now sentenced the American hostages to 76 more days of imprisonment.” (Seventy-six days is the time between the election and the Inauguration.)

Additional evidence lends credence to Bani-Sadr’s account. When labatabai resumed talks with the State Department in September 1980, military equipment headed his list of demands. But. unaccountably, on October 22, Iran dropped all references to these supplies. “This occurred because Iran had been guaranteed another source of U.S. arms.” explains an Iranian journalist.

Whether or not an agreement was reached between Khomeini and the Reagan Bush campaign, the fact remains that the ayatollah achieved all of his objectives by the time the hostages were released. He humiliated the U.S., got rid of Carter and “the criminal shah,” secured the transfer of four billion dollars in assets to Iran and ensured a steady flow of U.S. arms to his military. The faithful might praise Allah, but the glory was all Khomeini’s.

Israel And Arms

On July 18, 1981, a cargo plane returning to lei Aviv from lehran strayed into Soviet airspace and was shot down by a MiG-25 along the Soviet-Turkish border. According to the London Sunday Times, the plane was chartered by a Swiss arms broker, who intended to send 360 tons of military hardware—worth $30,000.000— to the Iranian military. Three shipments of American-made spare parts for M-48 tanks (which formed the bulk of Iran’s land forces) had made it through before the cargo plane was shot down. The Israeli foreign ministry denied any involvement, but several officials quietly conceded that their agents had sold Iran parts and arms shortly after Reagan took office.

As early as February 1981, Secretary of State Alexander Haig was briefed on Israeli arms sales io Iran. In November, Defense Minister Ariel Sharon asked Haig to approve the sale of F-14 parts to Tehran. While the proposal was in direct opposition to publicized Administration objectives, Sharon pitched it as a way of gaining favor with Iranian “moderates.” According to The Washington Post, Haig was ambivalent but gave his tacit consent, with the approval of top Administration officials, notably Robert McFarlane.

Israeli ambassador Moshe Arens later told The Boston Globe that Iranian arms sales had been discussed and approved at “almost the highest levels” of U.S. Government in spring 1981. In fact, Reagan’s Senior Interdepartmental Group agreed in July 1981 that the U.S. should tacitly encourage third-party arms sales to Iran as a way of “advancing U.S. interests in the Middle East.” The initiative was such a significant reversal of U.S. policy that it’s unlikely that Haig would have given his consent without the President’s knowledge and approval. Haig refuses to comment.

In November 1986. the Administration finally allowed that the Israelis had delivered U.S. military supplies to Iran in the early Eighties. The Stale Department downplayed the sales, claiming that the amount of arms Iran received was trivial, that only $10,000,000 or $15,000,000 worth of nonlethal aid had reached Iran. That figure was hotly disputed. The New York Times estimated that before 1983, Iran received 2.8 billion dollars in supplies from nine countries, including the U.S. A West German newspaper placed the figure doser to $500,000,000. Bani-Sadr said that his administration alone received $50,000,000 worth of parts. Houshang Lavi believes Khomeini got at least $500,000,000 in military supplies.

Lavi is in a position to know. In 1981, he and Israeli arms dealer Yacobi Nimrodi reportedly sold HAWK missiles and guidance systems to Iran. In April and October 1981, Western Dynamics Inter national, a Long Island company run by Lavi's brothers, contracted to sell the Iranian air force $16,000,000 worth of bomb f uses and F-14 parts. Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, William Caseys Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, said that the CIA knew in 1981 that Israel and private arms dealers were making sizable deliveries to Iran The Reagan White House raised no objections.

Eighteen months after Reagan took office, Iran had received virtually all the spare parts and weapons that Carter had refused to include in his hostage accord.

The Tower Omission

By the spring of 1987, no fewer than five Government panels (one by the President’s special review board, one by the Senate, two by Congress, one by Special Prosecutor Lawrence Walsh) were investigating charges that the Reagan Administration had willfully violated U.S. law—and its own policy—by secretly arming Iranians and funding the Contras.

As thorough as those investigations were, two glaring omissions are now coming to light: the CIA’s drug connection to the Contras and the pre-1985 arms deals with Iran. Little consideration was given to the possibility that the Iran/Contra initiative might have had its genesis in either Reagan’s 1980 Presidential campaign or in the opening months of his first term. It is difficult to understand why. The same names and many of the same methods keep turning up in both the Iran/Contra and the Debategate inquiries.

Many of the investigators have claimed that the issue was beyond their jurisdiction. The lower commission, for example, was an examination of NSC operations, not of Reagan campaign ethics. “We had a very simple mandate.” says Senator John lower, who ( haired the President’s special review board, “and that was to focus on the origins of the Iran/Contra initiative. It was an immense task, and we had 88 days in which to evaluate voluminous documents and interview the participants. We also had limited powers. We found no reason to expand our inquiry.” Both Senator Tower and Brent Scowcroft were former bosses of McFarlane, and Edmund Muskie was reported to have leaked While House information while he was Carter’s Secretary of Slate. 1 hose three men were the lower commission.

While the investigators were indifferent to Reagan's pre-1985 conduct, a handful of journalists pursued the charges: notably, Leslie Cockburn of CBS News. Alfonso ( .hardy of The Miami Herald and Christopher Hitchens of The Nation. Not until Flora Lewis, a columnist for The New York Times, published a piece in August 1987 that essentially promoted Bani-Sadr’s allegations. did Washington take notice.

Senate Majority Leader Robert Byrd weighed the evidence and became the first politician to link 1980 Reagan campaign practices with Irangate. He made an impassioned plea for truth on the Senate floor on August 7, 1987: “The secret policy of arming the ayatollah max have begun early in the Eighties... this bribery-and-ransom strategy was on the minds of the inner circle of Presidential advisors even before his Administration look office. What other explanation is there for the al-legal ion ... of a meeting between Mr. Allen. the first security advisor to the President, and a campaign official, who apparently met with Iranian officials and who may have been linked to Israeli shipments of weapons to the ayatollah in the early Eighties. This raises disturbing questions about the longevity of this ill-conceived arms-for-hostages strategy. It needs further investigation, in my judgment?

Represent alive John Conyers, Jr., chairman of the Criminal Justice Subcommittee, is beginning that investigation. “It's going to be difficult.'’ says Frank Askin. Conyers’ special counsel. “Some of the people implicated are in protracted legal battles. Some have reason not to talk I don’t expect them to be very helpful.” Conyers must soon decide whether the evidence warrants—and the public can tolerate—yet another Congressional investigation.

The Debalegate and Iran/Conlra affairs have already proved that members of the Reagan Administration engaged in deceit on an impressive scale. Whether they committed greater crimes has yet to be tested under oath. One thing is clear: The story is significantly more complex than the public has been led to believe. There are too many secret deals, too many memory lapses and shredded documents for the file to he closed with any conviction.

• The Wall Street Journal, Friday, June 10. 1988: “October Surprise?”

Speculation is raised about an Iranian hostage ploy. A National Security Council staff memo warns that Iran may try to use the nine American hostages in Lebanon as political pawns during the Bush-Dukakis race. 1 he memo, written by Middle East specialist Robert Oakley, foresees possible offers to release some hostages before the Nov ember elections. The price, some officials think: a promise that Bush would soften the U.S. anti-Iran stance. An Iranian official recently tried to arrange a clandestine meeting with a Bush aide, whose colleagues told him he would be “crazy” to meet secretly with Iran. U.S. officials say. The speculation is partly aimed al deterring any temptation to make a deal with Iran.